These books by Black Authors covers a range of Historical events, eras and figures that higlights the rich history of the continent.

There are a plethora of books out there proclaiming to truthfully capture the continent’s rich history, but they aren’t all worthy of our time. Infact many of these ones we grew up reading in Schools Textbooks do fall into this category. These often one-dimensional did little to capture the Africa’s Multi–faceted history and were mostly told from a European framework reference.

Nanjala Nyabola is a Kenyan commentator giving opinions with a focus on politics, war, social justice, books, and feminism. She contributes opinions to a variety of media outlets including the BBC, Al Jazeera, Okay Africa, The New African, The Guardian (UK), Foreign Policy, and a raft of many others.

Nyabola has contributed to two publications in the recent past including Africa’s Media Image in the 21st Century: From the “Heart of Darkness” to “Africa Rising” (Communication and Society) edited by Mel Bunks, Suzanne Franks, and Chris Patterson. Her other contribution is to African Women Under Fire: Literary Discourses in War and Conflict which was edited by Pauline Ada Uwakweh.

Books like these, however, don’t represent the fullness of African historical text that does exist. Throughout the 20th Century, Scholars like Senegal’s Cheikh Anta Diop and Ghanaian’s Kwame Arhin produced works that added perspectives to the African Historical landscape. In a more contemporary sense, there are historians from Africa and Diaspora who are furthering this works and-though still largely underrepresented many of these Scholars are women.

In the past decades, Black authors have taken to writing history that expands viewpoints, adding layers of nuance and authenticity to the field and offering critical works that experiments with format and examine eras, events and figures from the continent’s historical past. These books which covers a range of topics like the historical role of media in Kenya politics to the Aftermath of the Marikana Massacre in South Africa, explore lesser known histories and extend beyond typical narratives.

If you are interested in becoming more familiar with these stories, here are Several recent African history books to check out;

1) DIGITAL DEMOCRACY, ANALOGUE POLITICS: HOW THE INTERNET IS TRANSFORMING KENYA (ARGUMENTS) by Nanjala Nyabola

This contemporary history book, documents Kenyan society’s singular relationship with Digital Media and Online Activism. The Country is considered one of the most connected and digitally advanced on the Continent, with notably high numbers of Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp users.

The digital space has birthed several Online movements, thus allowing for many Kenyans to find Political agencies online. Many users, particularly those from Traditionally marginalized communities, have utilized social media as a valuable tool to challenge the government and to fight against Censorship.

Kenya is often dubbed Africa’s ‘Silicon Savannah’ because of the success of digital innovations such as Ushahidi, a crowd-sourcing platform for social activism, and the widespread use of Mpesa, mobile money. The Kenyan government has celebrated this ‘branding’. A perhaps unintended consequence (for the state) of the celebration of this narrative has been a dynamic digital space, in which many Kenyans, whose voices would not otherwise be heard in analogue public spaces, have been able to question the social and political systems of the country, as well as connect with like-minded individuals to articulate new radical political agendas. Although the state has tried to stifle these conversations through various means such as the 2016 Information Communication and Technology Bill, its commitment to project itself as liberal and ‘high-tech’ has allowed these digital spaces to flourish. How should the story of these spaces be told?

While Cambridge Analytica might be best known for harvesting millions of Facebook users’ personal data to meddle in both the UK Brexit referendum and the 2016 US presidential election, the consulting firm has also had a hand in influencing elections in the Global South. In Kenya, as Nairobi-based author and activist H. Nanjala Nyabola notes in a recent essay for the Centre for International Governance Innovation, Cambridge Analytica mined voter data to aid President Uhuru Kenyatta’s campaigns in 2013 and 2017, exploiting the country’s deep tribal divisions.

Since Kenya’s 2007 election, Nyabola writes, regulating hate speech and disinformation has become much more challenging. Digital platforms — such as Facebook, Twitter and Google — play a significant role in challenging negative stereotypes about political behaviour in the country and making room for citizen agency. But they also contribute to the spread of radicalized and fake content, and they often operate outside of existing regulation. What should the approach to platform governance look like? And what happens when companies — Cambridge Analytica, for example — engage in what Nyabola calls “digital colonialism”: the harnessing of those platforms to influence politics in countries far from the one in which they’re based?

Following the publication of her essay, we spoke with Nyabola about Kenyan politics in the digital age, why she advocates for a balanced approach to platform regulation and the need for a “more sophisticated conversation” around the impact of technology on society.

[Tsalikis]Your most recent book is Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics: How the Internet Era Is Transforming Kenya. What would you like people to know about how digital technology has affected Kenyan politics?

[Nyabola] As I argue in all of the pieces that I’ve written, and in the book, you can’t understand how tech is going to affect a society if you don’t understand the society in question. What I think is interesting about misinformation in the political space in Kenya is how it intersects with foregoing patterns of misinformation — how the digital amplifies things that have been happening before. In Kenya, we have a long history of rumours and political misinformation, coming from the state especially. I say in my book, and I’ve said many times in public, the number one purveyor of fake political news in Kenya is the government of Kenya. That has a lot to do with state control and state capture of traditional media, and how the period of free press in Kenya has been greatly compromised, especially from the pre-digital era into what I call Kenya’s first “digital decade,” from 2007 to 2017.

All of that by way of context to say what we’ve seen in Kenya is an interesting action and reaction. Many of the things that people are afraid of in other parts of the world are coming to play, and that’s where the Cambridge Analytica piece comes in. We’re seeing Western [companies], and also companies from China and other parts of the world, coming and spending significant amounts of money, or being hired by political parties to influence the information that is created and shared in the digital space. That could be social media manipulation, it could be fake news websites, it could be creating fake websites for a specific politician — that was really big in 2017. Some of the companies are local, some of them are international working with local partners.

The fundamental reason why this happens is because there is a lot of money in African politics. There’s a lot of money in Kenyan politics. And not just big money by Kenyan standards, but big money by global standards. What I say in the book is this brings out the parasites — that has to do with the changing nature of global capital. The digital frontier itself is new but the idea of mercantilism — foreign capital going to “explore” the rest of the world on behalf of power — that is not new. That’s why I call it digital colonialism, because it’s replicating the contouring of colonization.

The platforms on which much of this disinformation is being spread are not owned by Kenyans, are not controlled by Kenyans. So what does accountability for political misinformation look like when a British company uses an American platform to influence political discourse in a Kenyan election, [and] that results in deaths and destruction in Kenya? What does accountability look like in that framework? I think this is going to be one of the most urgent questions that we’re going to have to deal with in the coming years.

What are the challenges that come with political discourse shifting to online spaces, especially in an election context?

[This shift] is fundamentally changing the way in which people process political information. We’re going to have another election in 2022 in Kenya, and it’s going to be the first election with the first generation of “digital natives” — people who are [roughly] between 18 and 25. These are people who don’t remember what Kenya was like before mobile phones were everywhere and the internet was everywhere. These are people who don’t know how to read newspapers. That’s not a disparaging statement — it’s just the way print media has gone in the country; newspapers became incredibly expensive, a luxury item. That is also part of the broader narrative of state capture. At the heat of the democratic moment in Kenya, the biggest sites for criticism of the state was print media. That is why they sustained so much attack and co-optation from the state.

What does accountability for political misinformation look like when a British company uses an American platform to influence political discourse in a Kenyan election?

So now we have a print media that is reluctant to be the voice of criticism, that has retreated, and we have these kids who don’t know what it is to sit through a 30-minute news broadcast, don’t know what it is to read a newspaper cover to cover, don’t know what it is to be confronted by information complexity. I’m not even just saying that people are getting their news from Twitter, because that’s not the case; it’s coming from blogs, it’s coming from WhatsApp messages that have been forwarded to you. It fundamentally changes the way you consume and understand political complexity.

Sixty percent of Kenyans are below the age of 35. So we are going to be confronted with a new political reality, and a new reality for political information. That’s why, to me, this is going to be an incredibly urgent question: how are people supposed to think about politics when the traditional tools that we use to communicate political information have retreated, and the new tools are increasingly not fit for purpose?

What would you like to see when it comes to platform governance?

I think the first thing is that we need to keep up the momentum that we’re seeing on platform accountability. A lot of these platforms have gotten away with this “we’re the good guys” sort of “white hat” narrative, and not really been held accountable or taken to task for the negative outcomes. I’m not a Luddite, I’m not anti-tech. It’s just a question of…realizing that the things that people do at the platform level have consequences at the social level, and sitting in the discomfort of that, and forcing these platforms to sit in the discomfort of what disruption means. It’s not just a fancy word that you throw around at conferences; what does it actually mean and how do you deal with that?

So, I want to see a little bit more accountability for platforms at the legislative level. In the United States we’re seeing a lot more of that. I think Singapore also has done a lot on this, for better or worse. More parliaments bringing these tech executives into a room and saying, Well, if you’re going to operate here, it’s not going to be a mercantilist sort of frontier market approach. There’s going to be legislature and social political frameworks in which you have to operate. That’s one thing.

At a social level, I want to see more investment in understanding the societies in which this tech is deployed. To me, this assumption that developing countries are blank slates onto which technological fantasies can be projected is really dangerous. What we’re seeing is the consequences are usually far more grave than they are in countries that have robust legal and political frameworks. We’re talking about Myanmar and genocide, about Ethiopia and this escalation of hate speech leading to what some people are calling…a campaign of ethnic cleansing, influenced greatly by Facebook posts. We’re talking about elections that fall apart and people dying in Kenya.

This fantasy that you can just build platforms in Silicon Valley and spread them around the world without having to engage with the realities of the societies in which you’re projecting, I think, needs to be challenged at a social level. To me, that really boils down to bringing human beings back into the conversation, through engaging with social sciences and humanities — and people. Tech cannot continue to live in a conceptual bubble away from the reality of human behaviour and human history.

How would you approach the regulation of digital platforms? Are there lessons to be learned from the traditional print media model?

In Kenya, like I said, the internet replicates the contours of what went before it, occupying the space that the traditional media abdicated. [With] print media, there was awkwardness, but then there were the right questions asked, and then the right type of regulations were developed. Some of that was self-regulation and some of it was state-driven regulation, and you have this sort of complex synergy between the two. You have, for example, guidelines that media houses set for themselves, but then you also have legislation. Just about every country that has aspirations of a free press is constantly having this interaction between self-regulation and state-driven regulation.

What I want us to have is this kind of complexity and this conversation when it comes to platform governance. I don’t like the black-and-white nature of the current conversation, which is like, it’s either all or nothing; you’re either all self-regulating or it’s all state-driven regulation. That’s not the reality of a lot of sectors — the truth is you need both. So that’s what I would love to see: for us to sit in the complexity of what regulation could look like, and really start to ask those questions.

How does social media amplify existing inequalities in society — and how can those responsible for building platforms and apps guard against that?

To me, first you’ve just got to bring people back into the room; you’ve got to bring human nature and human behaviour back into the room. That means having a really good understanding of how people have behaved in the past, and how people are likely to behave in the future — and not how you want people to behave, which is a lot of what this predictive, speculative building is doing.

You have to build for inclusion, you have to build with perspective, and you have to build with intention. [You need to ensure] that you’re not just building things and hoping for the best, that you’re not building things that don’t reflect the reality of human history and human behaviour, and that you’re not building things that in and of themselves will intensify existing power imbalances.

Tech cannot continue to live in a conceptual bubble away from the reality of human behaviour and human history.

I think a lot of times when critics or analysts speak people tend to interpret it as tech pessimism and I’m very careful to emphasize it’s really not; it’s just about providing that reality check so that people can have a deeper perspective. I think especially when it comes to Africa and policy making, and tech, we’ve seen so much unchecked optimism, and tech companies being given an incredible amount of power. The concerns of the citizenship and of ordinary people are kind of a distant fourth, fifth concern. What people might be missing is that people are not rejecting technology; we’re asking for a more sophisticated conversation around the impact of technology on our lives.

In her debut book, Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics: How the Internet Era is Transforming Kenya, Nanjala Nyabola argues that current scholarship about ‘tech in Africa’ tends to be framed in overly simplistic developmentalist terms, and fails to account for state agency and the politics in offline spaces that have everything to do with what happens online. She pushes back methodologically against these reductive narratives by telling an empirically thick, descriptive story of the terrain through which power operates in Kenya (Africa is not a country), and the way in which it sizzles and congeals at the intersection of the traditional public sphere and the extension of this sphere online. She deliberately refuses to engage with the naive, optimistic view that more technology = more democracy.

Nyabola demonstrates that the Kenyan media’s structure of ownership and its reliance on state-sponsored advertisements have shackled the narrative it chooses to tell to a very specific bourgeois nation-building story. This story fails to reflect the lived reality of most Kenyans. Importantly, she dwells on the difference in content in inward-facing local-language media as well as that of the formal, outward-facing English media in constructing diverse stories. I would have loved to have seen a more detailed characterisation of local-language media and other forms of non-traditional means of communication, such as plays, fiction, music etc, which the author mentions in passing, in the crafting of different national narratives. Given these offline conditions, digital platforms offer Kenyans a low-barrier alternative to tell their stories and insert themselves into the public sphere.

The first part of Nyabola’s book describes the political conditions at the time of the Kenyan 2007 election, which primed the country for digital change. The collapse of the National Rainbow Coalition dashed the hopes of the Kenyan public, who believed that the corrupt years of former President Daniel Arap Moi’s regime were over. Instead, the perception that the government had become increasingly ethniticed polarised the public. When irregularities in the 2007 election were discovered during its broadcast, simmering tensions exploded and violence ensued. Live broadcasts were banned, muzzling the Kenyan press. An educated, concerned diaspora and a public hungry for news were thus caught between the fury of an international press and the tame, self-censored Kenyan media. The internet served as a space for information dissemination during this critical period. Nyabola states that it was at this time that blogs that had formerly been apolitical became sites of heated political debates. The internet thus created space for new discourses, and allowed for new imaginings of statehood and identity.

Nyabola argues that the contours of these platforms have not been adequately studied in the Global South. She writes that this is because of the ‘sociology of absence’: the idea that because the story of these platforms play out in Western media, the experience of using these platforms in Kenya is irrelevant. However, Nyabola demonstrates that this simply is not the case. Cambridge Analytica are believed to have used the 2013 Kenyan elections as a testbed for the methods they were later to deploy elsewhere. If the world had been paying attention, the current crises regarding interference in the US election and Brexit referendum might have been averted

Nyabola focuses on Twitter because she argues that it allows users to share public content and engage with each other, in comparison to Facebook where engagement is limited to a friend’s circle. Nyabola acknowledges that digital illiteracy and infrastructure barriers, such as a lack of electricity or an internet connection, nonetheless limit the number of people who are online in Kenya. She notes that in 2018 there are now one million largely English-speaking, urban Kenyan Twitter users and ten million Whatsapp users in a country of around 50 million. It would have thus been interesting to see a systematic comparison of the usage of these platforms, and their respective relationship with analogue political agendas.

“A timely and hugely important work. It chronicles how digital disruption is also an African emancipation, allowing a generation to leapfrog from the so-called Third World into the First and into an exciting beyond.”

— John Githongo, journalist and founder of the Inuka Kenya Trust

“Incisive, deft, and innovative, this book describes viral trends and critically expands the scholarship on Kenyan politics while bringing the social histories of marginalized Kenyans into sharper focus.”

— Brenda N. Sanya, Colgate University

“In this highly accessible and timely account, Nyabola moves Kenya and Kenyans from the margins of analysis to the very center, revealing how local realities help to bring out both the worst and best of the new digital age.”

— Gabrielle Lynch, University of Warwick

“Anchored in an eloquent grasp of Kenyan history, Nyabola maps the contours of advances, innovations, and regressions across Kenya’s digital sphere. This is essential reading for understanding contemporary Kenya.”

— Grace A. Musila, University of the Witwatersrand

Nyabola argues that the contours of these platforms have not been adequately studied in the Global South. She writes that this is because of the ‘sociology of absence’: the idea that because the story of these platforms play out in Western media, the experience of using these platforms in Kenya is irrelevant. However, Nyabola demonstrates that this simply is not the case. Cambridge Analytica are believed to have used the 2013 Kenyan elections as a testbed for the methods they were later to deploy elsewhere. If the world had been paying attention, the current crises regarding interference in the US election and Brexit referendum might have been averted.

Despite the Kenya Integrated Election Management System (KIEMS) that was put in place to prevent the manipulation of election results, the massive irregularities that took place resulted in the Supreme Court annulling the election results. Nyabola provides a detailed description of how KOT galvanised itself to take photos of results at polling stations to compare with the broadcast results, and played a key role in holding the process accountable in the public sphere. Through this example, she shows that no amount of technology can ever replace the intentions of the state.

What this book makes clear is that Kenyans are determined to reclaim the agency to shape their own stories. Nyabola has beautifully told the story of how they have done this so far via digital platform.

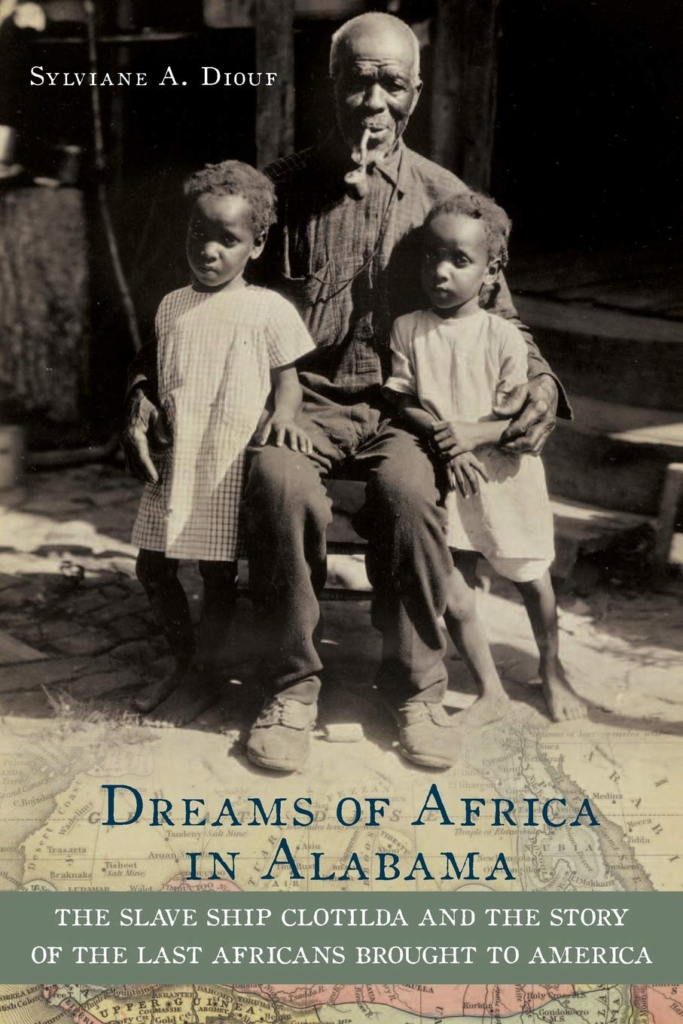

2) DREAMS OF AFRICA IN ALABAMA: THE SLAVE SHIP CLOTIDA AND THE STORY OF THE LAST AFRICANS BROUGHT TO AMERICA by Sylviane .A. Diouf

The Story of the last slave ship to reach American soil is conveniently overlooked in the history of Transatlantic Slave trade, but this book by Senegalese author Slyviane .A. Diouf brings this dark history to light. Landing in Alabama on the thick of the night during the summer of 1860, the ship Clotilda carried the last groups of enslaved Africans who were trafficked from Benin and Nigeria in to the United States completely unnoticed. This occurred nearly 50 years after slavery had supposedly been Abolished and was the result of a bet by a shipyard owner.

This book traces the groups of enslaved Africans history, from their capture in West Africa to their lives as enslaved people against their American-born counterparts. This books also follows the groups Post-Emancipation, documenting the strong cultural tides that persisted despite their circumstances, and led to many to purchase land and form their own settlement as African Town, in which they spoke their own language maintained Traditional African laws.

In situ photograph of bead strand around pelvic area of Burial 340, New York African Burial Ground.

Historian Sylviane Diouf’s book, Dreams of Africa in Alabama contributes to expand our understanding of slavers’ “paths and diversions” through a well-crafted and gripping biography of the Clotilda, the last documented ship to import enslaved Africans into the United States. The “social life” of the schooner Clotilda began in 1855 in Mobile, a southern city described by the author as the “slave-trading emporium of Alabama”, where her rigging was announced by a local newspaper. Built by William Foster, a famous ship carpenter, who happened to support the extension of slavery to Central America, she was bought for $35,000 by a wealthy local businessman and slave-holder, Timothy Meaher. The “genealogy” of the Clotilda’s voyage to the coast of Africa in 1860 includes another illegal yet successful operation led in 1858, when the Wanderer left New York to collect four hundred slaves in the Congo River area and smuggled them back into the United States with almost complete impunity. Indeed, after being summarily altered to serve her real purpose–slave trading–and then disguised to avoid detection by an African Squadron in charge of repressing a commerce outlawed in the United States since 1808, the Clotilda crossed the Atlantic and landed in Ouidah, Dahomey. After a brief stay, she was on her way back to Mobile with one hundred and ten Africans on board. Minutely reconstituted by Diouf, the details of the intricate scheme devised by Meaher to unload the Clotilda’s human cargo reveal the complicities he enjoyed among the court officials in Alabama as well as the extent of his local clientele. Indeed within hours, Meaher managed to mobilize no less than three boats to haul the Clotilda and relocate the Africans. He also sold the Clotilda’s human cargo in a matter of weeks, except for the thirty-two slaves he kept for himself. On his order, the slaver, whose voyage had already attracted intense media coverage, was burnt and sunk in a bayou: although, as Diouf stresses, “her hull remained visible at low tide for three quarters of a century, as if to remind everyone of the Africans’ ordeal,” her owner not only escaped official investigation, but became a state hero of sorts. The Clotilda’s “afterlife” has been marked by a series of debates regarding her actual location, and the authenticity of parts (allegedly taken from the wreck) that have been put up for sale on the Internet. The outcome of an underwater archeological investigation, carried out in the last decade of the 20th century, was disappointing. Dreams of Africa in Alabama must therefore be credited for establishing the historicity of the Clotilda’s 1860 slaving expedition, often omitted, disregarded as a hoax, or misrepresented in specialized literature.

Components of necklace found with Burial 72, Newton plantation cemetery, Barbados. Dog teeth, fish vertebrae, money cowry shells, European glass beads and, in the center, a carnelian bead whose origin was undoubtedly Cambay, India. For details on these components, see Handler 1997

In the study of the Clotilda as a cultural commodity, both intended for exchange and facilitating exchange in the business of slavery, Dreams of Africa in Alabama is also a ground-breaking analysis of the slave ship as a social space and a mobile community bound by water, to borrow Jane Webster’s concepts, with an emphasis on the enslaved majority. The first section of Diouf’s essay describes the historical forces and individual agencies that brought together one hundred and ten people from various places in today’s Benin and Nigeria onto the last slave ship bound for the United States. The shipmates’ experience of the Middle Passage is then reconstituted on the basis of a series of interviews conducted by several scholars, novelists and journalists until 1935, when 95-year-old Oluale Kossola aka Cudjo Lewis, the last and most famous of the Clotilda’s survivors, passed away. The author’s reference to other slave narratives (Equiano’s, Baquaqua’s and Cuguano’s most notably) and her own authoritative insights shed a useful light on their ordeal. A third section examines the array of strategies employed by the shipmates–both on the plantation where they were kept for almost five years and as freed-men and women in the post-abolition South–to preserve the sense of community they had developed on the Clotilda; an effort that materialized with the foundation of African Town circa 1867. The epilogue focuses on the various attempts made by Africatown, a community that today boasts three thousand inhabitants, to preserve the legacy of the shipmates’ experience in America.

In situ photograph, Burial 72, Newton plantation cemetery, Barbados; metal bracelets can be seen on each arm.

A specialist of the cultural history of economic migrations from Africa to the West–as attested by her previous publications, most notably Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas (1999) and In Motion: The African-American Migration Experience (2005)–Diouf has developed a methodology that incorporates the Foucauldian notion of history as a (transnational) “profusion of entangled events,” but examines both the patterns created by these successive entanglements in the longue durée, and in their local micro-manifestations. Material objects, such as the Clotilda slave ship and the bronze bust of Cudjo that was stolen in 2002 from the Mobile Union Missionary Baptist Church, are called upon to precisely “illuminate their human and social contexts”. Drawing from the vast amount of written and oral documentation she gathered in the United States and in Benin, Diouf delineates the specific impact of the trans-Atlantic slave trade on the lives and self-perception of marginalized African individuals, and the corrective effects of their personal decisions on the dynamics of macro-politics and economy. For instance, chapter two describes the political transition in mid-19th century Dahomey between King Ghezo and King Glèlè, and the kingdom’s subsequent involvement with tolerated slave trading towards Cuba, and “illegal” slave trading towards other regions of the Americas . These West African and Caribbean events are then correlated with the project of reopening the international slave trade, an idea that gained ground in the South of the United States, and to which Meaher, Foster and their clique obviously subscribed. In turn, the Africans they brought to Mobile in 1860 were caught in a web of political and economic developments at the local, regional and national level–the Civil War, the Abolition of slavery, the Reconstruction era and the Jim Crow laws, the Alabama convict leasing system, the Great Depression, and the Great Migration, to name a few. Diouf convincingly demonstrates that, though severely impaired by their social status as slaves, and then as Negroes/Blacks, and culturally isolated both as “bozales” in a largely creolized African American community and as Yoruba-speakers hailing from a region (the Bight of Benin) that did not traditionally supply the United States with slaves, the Clotilda’s shipmates chose to become actors in American social history. They learned English, kept their American or Americanized name after emancipation, petitioned to acquire a citizenship that ironically was granted to them and to their former owner at the same time , bought land, converted to Christianity, remarried, and registered to vote in spite of Meaher’s renewed intimidations.

They simultaneously managed to preserve the social and emotional bounds they had established while on the Clotilda, and periodically reaffirmed their will to return to their homeland in a concrete or symbolic manner. In her reconstruction of the Clotilda’s voyage, Diouf points out the a-typicality of the shipmates’ sex-ratio (50/50) and the percentage of children (50%) on a 19th century slaver, hypothesizing that Meaher and Foster, aware of the risks involved with importing Africans half a century after the abolition of slave trade, had an acute interest in the slaves’ longevity and reproduction. Her observations regarding the Clotilda’s demographics suggest that the last known American slaving operation may have deliberately taken the ignominious form of child trafficking. It reminds us also that more research is needed on childrens’ experience of trans-Atlantic slavery.

Abache/Clara Turner and Cudjo Lewis, 1912

The cargo’s average age may partially explain why Diouf takes issue with studies that systematically ascribe to Africans crossing the Atlantic a range of emotions that are well encapsulated in Stephanie Smallwood’s striking concept of “salt-water terror”. Without denying the terrifying aspect of each new phase of the whole process of deportation for its victims, Diouf insists on the shipmates’ ability to adjust to their mobile environment, to gather intelligence on the direction, length and purpose of the trip, and to look for opportunities that could reverse their fortune. For her, shame had to be the predominant feeling among people raised in accordance with an exacting code of honour (a notion discussed at length by John life in his 2005 essay entitled Honour in African History) when they were publicly stripped naked prior to boarding. This shame was not alleviated by the rags given to them upon arrival, as their imposed nakedness was then misconstrued in European and American imagination as an evidence of African primitiveness. “Decades later, the men and women who had boarded the Clotilda still spoke of the profound humiliation they felt when their clothes were torn off,” writes Diouf who quotes Cudjo Lewis confiding “I so shame! We come in de ‘Merica soil naked and de people say we naked savage’… Dey doan know de [canoe men] snatch our clothes ‘way from us’” .

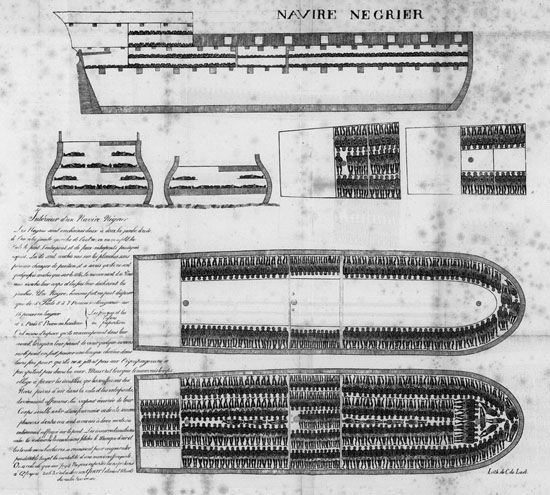

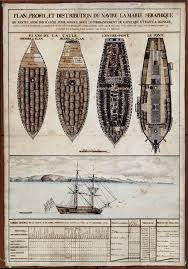

A French slaving vessel in the early nineteenth century showing how

enslaved Africans were packed into its decks. A description of conditions aboard the

ship, wherein the slaves “lay nude on planks,” is given in manuscript on the left

Along with shame, concern for family and friends and nostalgia for home prevailed among the deported Africans. They certainly perceived such a sudden and compulsory kindlessness–the prerequisite, as research on domestic slavery indicates, for enslavement in the societies where they came from–as the unambiguous sign of their imminent debasement. Diouf astutely proposes that the ship community, as an alternative initiation society, provides a metaphor for lost kin, and delays the deported individuals’ self-perception as slaves. She adds that “The solidarity, dedication, and mutual support of the shipmates did not end with the journey, but remained strong, sometimes through several generations in the Americas”.

The existence of such a bond among the people of the Clotilda is evidenced by their rule of mutual protection from physical abuse on the plantation; their preference for “endogamy” (Kossola/Cudjo Lewis and Gumpa/Peter Lee among others, married a shipmate); and Cudjo’s daring attempt, as the group’s spokesperson, to obtain from Meaher, their ex-owner, reparation for their deportation and five years of unpaid labour under the form of a land grant. As a community, they also persistently made plans to “go back home” until at least the 1870s, and possibly until they heard of the 1894 French conquest of Dahomey. Diouf sees “their failure at emigrating [as] part of a wider pattern”. Indeed, many Africans and African-Americans alike tried to save every penny, as the Clotilda’s shipmates did initially, to pay for their fare back home; some even wrote to the American Colonization Society, as the Clotilda’s shipmates did in 1873, to propose their services as missionaries to Liberia. But as Diouf suggests, “perhaps they were impeded mainly because they lacked the funds, and because the necessary information and infrastructure to facilitate or simply make possible their voyage was not in place”. Meanwhile, they continued speaking Yoruba among themselves, tattooed their children, and gave them African names to double those they received through baptism. Most importantly they instilled in them a faith in self-sufficiency and reserve, as well as pride in their origins: those values are apparently still cherished by some of their descendants.

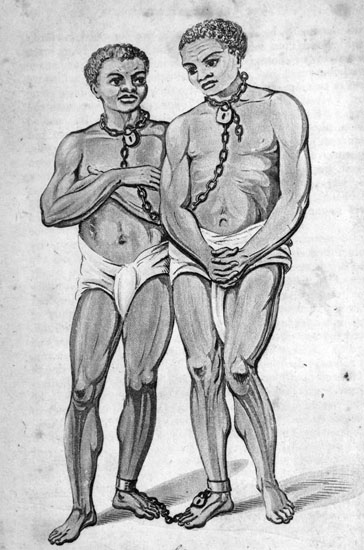

An engraving based on an eyewitness sketch by a British naval doctor, Sierra Leone, 1805. Captioned, “Slaves: Shewing the method of chaining them.”

The foundation of African Town represents the shipmates’ attempt to reconcile their everlasting dream of Return with the pragmatic choice they ended up making of integrating American society, and more specifically its Southern culture, provided that it was on their own terms. This process began with the “reinvention of tradition”, since the shipmates avoided clinging “to customs that would have made them stand out more than they already did,” according to Diouf. A town leader (rather than a king) was elected on the basis of his former social status but without consideration of his ethnicity–ironically, Gumpa, a Fon in the midst of a majority of Yoruba, was related to the royal family in Dahomey. Then new laws were passed and judges nominated. Over the years, adjacent plots of land were acquired, and residents built homes in the local style for their extended yet monogamous families, as well as all the institutions they needed for self-sufficiency, namely a church, a school and a graveyard. Cut off from the African continent, self-segregated, and somewhat enigmatic to its neighbours, African Town could be compared to a Maroon settlement, although it was highly visible and vulnerable to white supremacy. It qualified also as a “Black town” (90 to 95% percent black inhabitants, black founders, black control) though differing from other such communities because of its African majority.

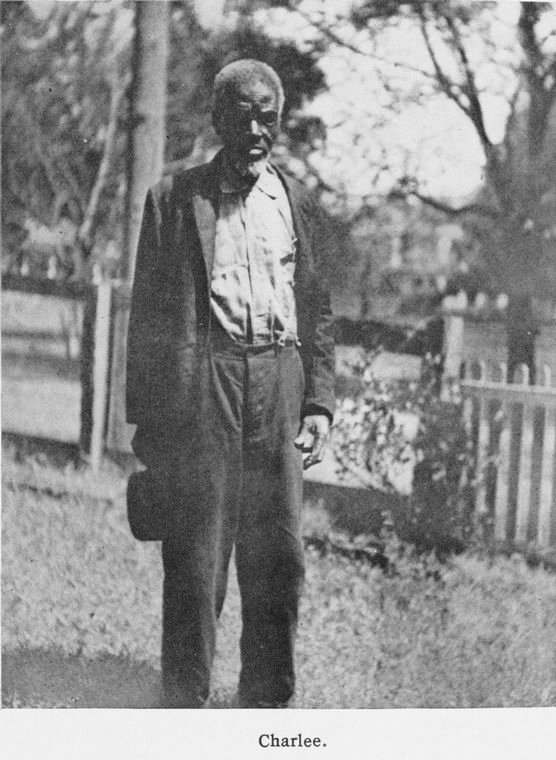

Charlie Lewis, 1912

The thorny issue of the relation African Town entertained with the rest of the African American community harks back to the days of slavery. The planters’ divisive policies and the myths they purposefully spread about Africa guaranteed that “salt-water slaves” such as Cudjo and his companions would be at best ignored by their “creole” co-workers, and often treated with contempt and hostility. Noah, a former slave on the Meaher plantation remembered for instance the hands’ amazement at the “on godly way that those Affikins found [to wear the coarse European clothes given to them,]” unaware that women may have attempted to wear them as pagnes. In the binary universe of the plantation, the fear inspired by the Clotilda’s shipmates, who had a justified reputation of people who “wouldn’t stand a lick from white or black,” did not help their integration either. Additionally, as they defined “whiteness” based on the individual’s place of origin, religion or behaviour, they did not particularly identify with African Americans; nor could they conceive of “the linkage between colour and servitude, because they saw ‘whites’ [that is mulattos] working in the field […],” writes Diouf in one of the most captivating passages of the book.

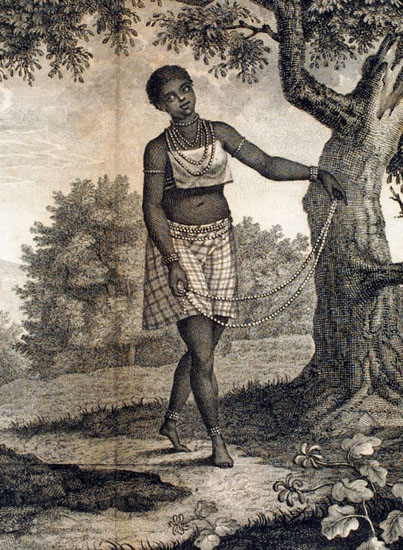

Wolof Queen Ndeté-Yalla, Senegal, showing her

robes and bead jewelry, 1850s; based on a drawing made from

life by a Senegalese Catholic priest

The Afro-centered logic and impeccable unity of the founders of African Town only increased its residents’ mysterious and slightly threatening aura. Though they had to endure the same oppressive conditions and developed the same forms of resistance as other Blacks, their status as land–and home-owners, self-employed or semi-skilled workers also set them apart. However, intermarriages and friendships brought constantly African Americans into their midst, and they attempted to bridge the gap with their neighbours with events such as gigantic free picnics organized by their church members. Their repute of moral rectitude may have caused the downfall of Cudjo’s and Abile’s eldest son. As violence escalated between African Town’s second generation and their neighbours, Cudjo, Jr. committed a murder, was sent to the state penitentiary, but released after six months thanks to a petition signed by Meaher’ son and other black and white Mobillians. “A man of excellent character” and possibly also a police informer, he was nevertheless killed by the sheriff two years later. His death inaugurated a catastrophic fifteen-year period for Cudjo who lost his wife and six children in a row. The cover picture, in which Cudjo poses around 1927 with two great-grand-daughters, is thus a palimpsest that evokes his heartrending tragedy.

Angolan woman, showing clothing style and bead

jewelry, 1786-87; based on a drawing made from life by a

French naval officer

Diouf’s Dreams of Africa in Alabama, a sophisticated contribution to “Slave Route Studies” with their stress on African continuities, exemplifies the new scholarship on African Diaspora at its best. It is an accurate rendition of the Clotilda’s shipmates’ “Odyssey without Return” that corrects countless mistakes made by previous writers on their origins, voyage and various other aspects of their lives, partly because of mutual borrowings or outright plagiarism. Moreover, it reconstitutes the enslaved Africans’ perceptions of their ordeal and its aftermath, de-emphasizing their otherness, while preserving the complexity of their relationship to both their place of origin and their place of residence.

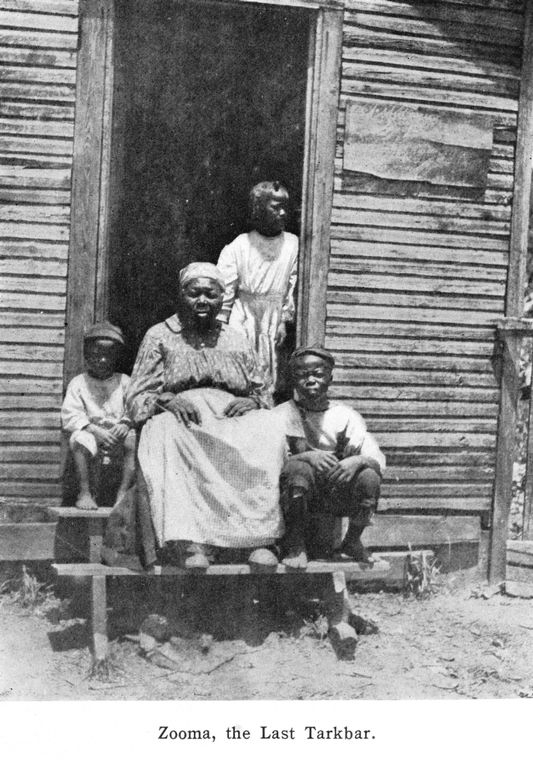

Zuma and her grandchildren, 1912

Highly recommended reading as we are celebrating the bicentennial of the official abolition of slave trade by Great Britain and the United States, Dreams of Africa in Alabama–co-winner of the 2007 Wesley-Logan Prize in African Diaspora History of the American Historical Association–offers also an invaluable window onto the hotly debated issue of “communautarisme”. It demonstrates eloquently that the shipmates’ secluded town inscribed in the Southern landscape their undying connection to Africa and irrepressible will to survive as Africans in America. Today, Africatown’s fifth generation is determined to preserve this heritage, obtain official recognition of its historical significance, and derive new revenues from it, against wide-spread neglect and vandalism, internal feuds, and industrial encroachment.

The history is also explored on the Posthumous New York Times Best Seller novel Barracoon: The Story Of the Last Black Cargo by Zora Neale Hurston written in 1927 and sourced from interviews with Cudjo Lewis who was 86 years old as at that time and was the last person to have survived the Slave Trade.

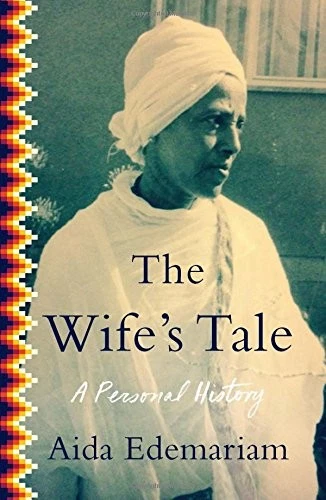

3) THE WIFE’S TALE: A PERSONAL HISTORY by Aida Edemariam

In this multi-generational account of the life of her 95-Year-Old grandmother Yetemegnu born in the northern city of Gondar in 1916, journalist Aida Edemariam highlights several shape-shifting moments in the modern Ethiopian history and it’s rapid transformation from Feudalism to Monarchy to Marxist revolution to democracy, which occurred over the course of just one century, as stated in a synopsis from Harper Collins Publishers.

The Wife’s Tale” is based on Aida Edemariam’s 60-hour long conversation with her grandmother, Yetemegnu Mekonnen (Nannye), that spans 20 years. By situating her grandmother as a central agent, Aida Edemariam tells a story that transcends the authority of the official archive, and its assumption to singular and credible knowledge.

Each chapter of the book is titled after a month of the Ethiopian calendar. Pagume, the 13th month, ushers in Yetemegnu’s intimate and exhilarating story. The rain on Ruphael’s Day, and its “thud, thud, thud” on the corrugated iron roof reminded me of my own childhood when my mother, just like Nannye, dropped frankincense on “coals huddled into a low clay pot—releasing sweet smoke that rose and tangled with the smell of roasting coffee.”

Attempting to bring the fragments of Yetemegnu’s rich and vast account into one narrative may have been difficult, and results in an occasional disjointed narrative that is sometimes hard to follow. But the narrator’s profound knowledge of Ethiopian history enjoyably invites us in regardless.

Mural, Ba’ata church, Gondar. Aleqa Tsega is on the left. Photograph: Aida Edemariam/Fourth Estate

Certainly, what amazed me most is Aida’s honed and nuanced understanding of her grandmother’s story through her own critical and profound awareness of the tumultuous 20th century history of Ethiopia. She takes us from the Italian occupation, to the 1960 coup d’état against Emperor Haile Selassie, to the revolution of 1974 and back again to the ingenuities of the Orthodox church, and to a sensibility of Ethiopian aesthetic. Along this magnificent and winding journey are many lives and relationships; Yetemegnu’s mother, husband, aunts and uncles, reveal their aspirations and desires. The church of Ba’aata Mariam, which once turned Emperor Tewodros II’s mother away when she brought her son to be baptized because she sold kosso (purgative) to survive, and could not “afford the two jars of dark beer, two bowls of stew and forty injera they demanded in payment,” became Aida’s major source of inquiry.

Yetemegnu was born in 1916 and married Tsega in 1924 in Ba’aata when she was eight years old. Tsega was born in Gojjam where he had gone to church school and where he had learnt the poetry of Ge’ez. It was Memhir Hiruy “famed throughout the country for his skill with qiné,” who first saw Tsega’s exceptional knowledge. He took him to Ba’aata Gondar to continue his studies where he was awarded aleqa-ship in 1926. And so Tsega’s turbulent and at once blissful relationship with Ba’aata begins, which the author dazzlingly portrays. For those of us who were brought up by fathers who were intimately connected to the Orthodox church, Tsega’s story melts with our own experiences and Aida helps us claim the story with pride. Being a native of Gojjam “where everyone knew the evil eye flourished,” complicated Tsega’s relationship to the people of Gondar and significantly so after he became Aleqa. It is through this brief account of Aleqa Tsega’s life that the subject of the book, Yetemegnu, evolves.

Married as a child, she did not know what the world of marriage meant or comprised. It was in her new husband’s house that she cried and played like a child. As for Tsega, “he worried whether she ate enough. “Lijé,” he’d say. “My child. My child is hungry.” Again, it was as if Aida was telling me the story of my own mother, who was also a child when she was first brought to my father’s house as his wife. So intimate is Yetemegnu’s narrative to my mother’s life, and to the lives of women who once lived through a particular moment of Ethiopian history, that we the descendants can truly imagine their deferred dreams and their anticipation for possibilities in the rapidly unfolding social and cultural transformations of the 20th century.

“Not infrequently,” Aida narrates, “he (Tsega) would arrive home to find her in a corner, weeping. Child, he would say gently, why are you crying—Ayzosh, ayzosh, he would murmur, drawing her to him. He would wipe away her tears and gently soften her taut and salty face. Ayzosh. I will be like a mother to you.” And at other times, a different Tsega would emerge: “Come here. Her stomach seemed suddenly to have slid to somewhere around her feet. Come here, I said. He raised a stick, and he did not stint.”

And yet as Yetemegnu expressed the frequent violence that her often kind and loving husband precariously inflicts she also conveyed her aspirations and her rebellious stance that she continually conceived. It is this complicated relationship between husband and wife that the author recreates in heartening words, in deeply affecting reflections and in meticulously written historical contexts.

Yetemegnu was only 14 when she had her first child, who later dies. Mariam, Mariam, Mariam, direshilin is a chant by midwives and others that Aida repeatedly inscribes to describe the performative setting of Yetemegnu’s 10 entries into motherhood. And through the recurring lines of Mariam, Mariam, the author brilliantly conjures this exhilarating chant that was performed by women during a time when there were no hospitals around. Certainly, what fascinated me most was Aida’s returning urge to articulate such types of cultural and social formations that are spread throughout the book. It is as if Aida wanted to understand her own unfamiliar journey to such experiences and that she also wanted to urgently remind the reader about notions of culture that were once important but are now completely erased from the memory of contemporary knowledge.

And then there is the absorbing story of the Italian occupation when Yetemegnu takes us to the war and to the prominent personalities of the time such as Ras Kassa, to his son and to his brothers who were executed by Italian fascists, and to Abune Tewoflos who later became the second Patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and who was Yetemegnu’s family friend. Tewoflos was executed by the military regime in 1974 with 60 other officials of the imperial government. He helped one of Yetemegnu’s sons, Aida, (who is the author’s father), to get a scholarship to Canada to study medicine. And after coming back, the son Aida would establish the first medical college in the country. Indeed, there were many other stories that revolved around the Italian occupation; the brothels that were frequented by Italians, Tsega’s administrative duties for 44 churches in Gondar, as well as the prayers of mercy by the deacons and priests of Gonderoch Maryam and Ba’aata. While it was Yetemegnu who told the stories to her granddaughter Aida, in the book it is as though their two voices have merged.

Another exceptional moment is Yetemegnu’s “wayward” experience with the zar, a ritual that can only be captured by one’s own lived experience. But with a vividly cinematic narrative, the author takes us through Yetemegnu’s recurring trance as if she felt and sensed the zar through her own imagination of Ethiopian myths and ancestral spirits. In other words, Aida locates the past in such a way that seems to converge with her own memory and identity.

We find in many parts of the book that the recording of Yetemegnu’s experience was not adequate by itself. It is only with the fusion of a deeply researched history and imagination that we get a fuller portrayal of Yetemegnu’s life.

In this remarkable book that also strikingly nudged my own memory, Aida tells us about Yetemegnu’s ordinary life, which in turn evokes the extraordinary lives of Ethiopian women who lived at a certain moment of history; our mothers and grandmothers whose stories are forgotten in contemporary memory. I vividly saw my own mother’s story through Yetemegnu’s tumultuous but amazing life. The narrative covers almost a century, since Yetemegnu lives to be 98.

Yetemegnu, subject of Aida Edemariam’s memoir, who lived through the Italian occupation of Ethiopia in the 1930s.

Edemariam uses his biological memoir of her grandmother’s life to reflect on social and political shifts that have occurred in the country, and their human toll. Yetemegnu lived through several transformative events in Ethiopian history such as the Fascist Invasion and the rule of the Emperor Haile Selassie. This uniquely human story, offers a “panoramic” view of history as well as an intimate look into how such events have impacted not only the growth of the nation but also the personal, everyday lives of Ethiopians. Told from the Often Overlooked perspective of a woman, the book also tackles the role of gender dynamics on individuals experiences.

Landscape around Gonderoch Mariam, near to where Aida Edemariam’s grandmother Yetemegnu grew up.

The Wife’s Tale introduces a woman both imperious and vulnerable; A mother, a widow, and businesswoman whose deep faith and numerous travails never quashed her love of laughter, mischief and dancing”, reads the book summary . A fighter whose life was shaped by direct contact with the volatile events that transformed her nation”.

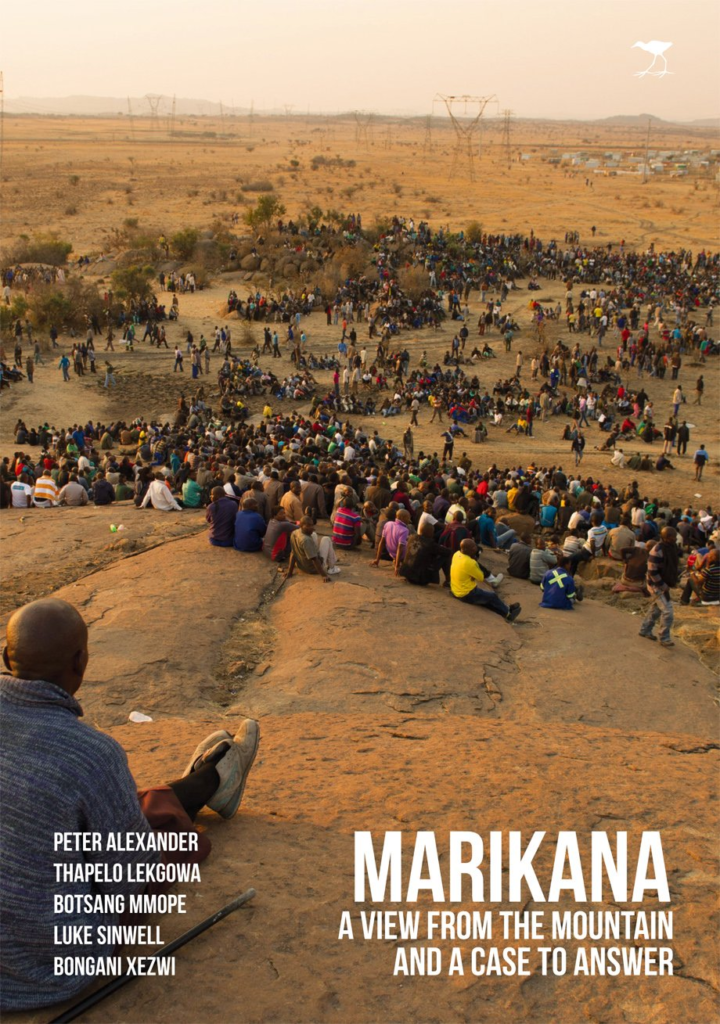

4) MARIKANA: A VIEW FROM THE MOUNTAIN AND A CASE TO ANSWER by Peter Alexander, Thailand Lekgow, Botsang Mmope, Bongani Xezwi

The Marikana Massacre of 2012, is known as the most deadly use of force by South African Police Forces against civilians in the 21st Century. The killings were in response to demands from Unions and Independent miners to have their pay increased to R12,500 a month. The violence led to a total of 34 deaths, while 78 Others were injured.

Marikana: A VIEW FROM the Mountain and A Case to Answer, which was published this same year, offers firsthand knowledge of the event, through ten interviews with surviving strikers. Many of the interviews were conducted at the very mountain where the miners would meet ahead of the protest. It also offers a retelling of the events from the strikers’ perspective, giving voice to those directly impacted by the violence, as well as detailed maps and photos of the area and the events that took place.

The book goes on to discuss the Aftermath of the Massacre and the Grave outcome of State-backfield violence against citizens, using it as a vehicle to discuss the intersections of race and class in Post-apartheid South Africa. “The book is an attempt to provide a bottom-up account of the Marikana Story, to correct an imbalance in many official and media account that privilege the viewpoints of governments and business, at the expense of workers”, says Jane Duncan the Highway Africa Chair Of Media and Information Society at the School Of Journalism and Media Studies, Rhodes University Of the Book.

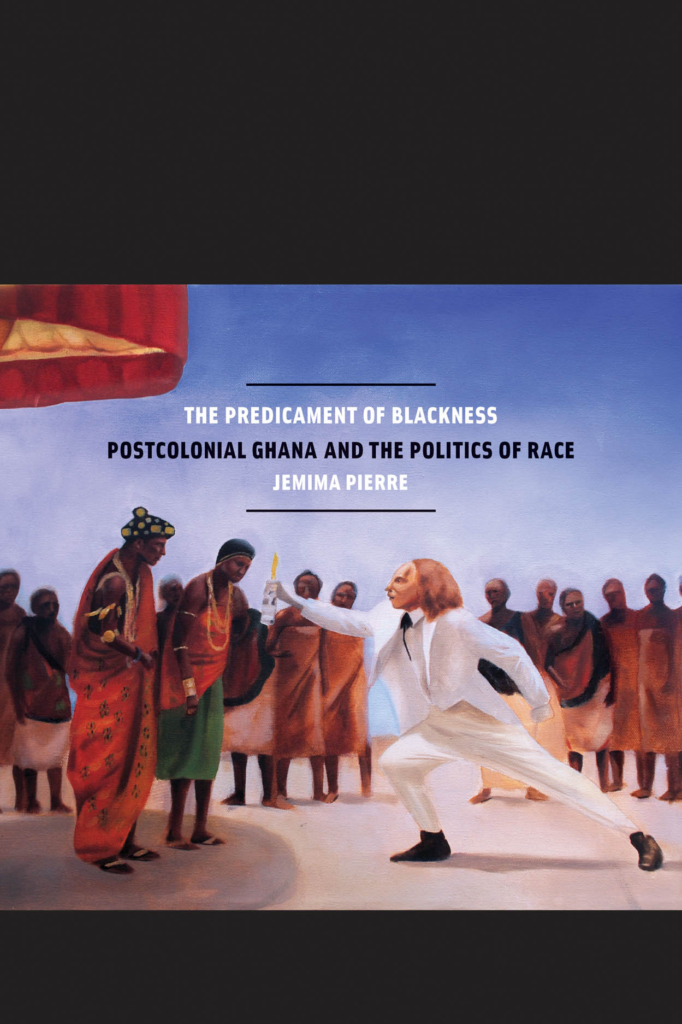

5)THE PREDICAMENT OF BLACKNESS: POST COLONIAL GHANA AND THE IMPLICATIONS OF RACE by Jemima Pierre

Described by the Chicago Press as “the first book to tackle the question of race in West Africa through it’s Post-Colonial manifestations”, these books examines the implications of the concept of “Blackness” on the Continent, using Ghana as a Cultural backdrop.

Jemima Pierre, professor of anthropology at Vanderbilt University, has written an ambitious book in The Predicament of Blackness: Postcolonial Ghana and the Politics of Race. She engages Ghanaian and African diasporan constructions, perceptions, and performances of Blackness and Whiteness in contemporary Ghana. By doing so, she brings anthropology into an ongoing conversation on race within African studies dominated largely by historians and South Africanists from a variety of specializations. The book, she says in her preface, is an “ethnography of racialization that insists on shifting the ways we think about Africa and the history of modern identity” (xv). She argues that the process of racialization within the framework of global white supremacy links continental Africans and people of African descent in the diaspora. Race matters, to Pierre, and she culls ethnographic material from her two decades of research in Ghana that belies its irrelevance in every day urban Ghana.

Jemima Pierre’s The Predicament of Blackness is an ethnography of racialization that interrogates historical processes of racial constructions and the dislocation between disciplines of African diaspora studies. Positing Ghana as an example, the overarching thesis of this book postulates postcolonial African societies as formed under structures of global White Supremacy. The Predicament of Blackness culminates Pierre’s five collective years of research and nearly two decades of time in Ghana. It looks to provide a theoretical reconfiguration of race relations in contemporary African space and its relationship with the diaspora. And provide it does: It is innovative in establishing the occurrence of racialization in contemporary Africa as a fact. Its theorization will help to lead a more accurate and forthright discussion among the disciplines of focus. The Theoretical objective of this book is to contextualize contemporary racial formations in Africa by interweaving historical background with case studies. Ghana’s particular role in this analysis is justified by its central role in Pan-African politics and culture that “resonate across the various fields of African diasporic culture.”

She was inspired to write this book, Pierre tells us, by the failure of African and African diaspora studies scholars to “fully appreciate the sociohistorical reality of Black identity formation on the African continent and its articulations with global notions of Blackness” . Actually, there is a wealth of impressive scholarship that directly or indirectly addresses race and related issues in Africa. More on this below. Still, Pierre’s observations provide a rich and textured documentation of the meanings and expressions of blackness — and, ultimately “Whiteness” — in early 21st century Ghana. The predicament, she suggests is that Whiteness serves as a reference point for Ghanaians’ notions of beauty, Blackness, and power, but Ghanaians remain blind to this and the framework of global white supremacy that has contributed to the social and political structure of their society.

As a historian of Africa I found Pierre’s effort to provide an alternative to the romantic readings of Ghana’s late colonial and early independence periods particularly noteworthy. In the chapter “Seek Ye First the Political Kingdom” Pierre argues, in short, that the nationalists, Nkrumah among them, failed to dismantle the racialized structures of imperialism. Rather than revolutionary or dramatic change they settled for safeguarding their positions of power.

“Nkrumah and his political party, the CPP,” writes Pierre, “made compromises that reflected the contradictory nature, and compromised position, of a nonrevolutionary transition mediated by and through the terms of the former colonial master”.

She strips some of the veneer from Nkrumah’s pan-Africanist, revolutionary façade and describes decolonization as more politically and culturally conservative than radical. The ruling Convention People’s Party, she rightly states, spent more time consolidating power than uprooting the remains of the colonial system. This is not merely history, she suggests, because the consequences of these choices had implications for present-day Ghana. While not necessarily original — she does not claim that it is — this is a wonderful point of departure to revisit Ghana’s nationalist period.

Pierre is strongest with her interpretation of her interviews on discreet issues, which expose individuals’ or small groups’ unconscious racial reading of a practice or people. Throughout chapter four, to offer one example, she unpacks skin bleaching and associated ideals of beauty among those who do and do not practice it.

This discussion and a brief etymology of “mi oburoni” — my white/light person — as a term of endearment demonstrates the degree to which the Ghanaians Pierre came into contact with imbibed whiteness and/or light skin as preferable to the darker skin of most Ghanaians.

As a work of anthropology this book captures a slice of Ghanaian views within a specific historical moment. But the slices will look different as we move away from the coast to explore how urbanites in the interior cities of Kumasi and Tamale conceive of the intersection of blackness, beauty, and power. I suggest that a broader geographical and historical framework would complement Pierre’s ethnographic analysis and align her study more closely with its aspiration to document racialization in urban Ghana. This would include accounting for the diversity of African responses to the European imposition of a racialized power structure. For example, along the coast from the closing decades of the nineteenth century through World War II, the so-called colonial African elite in Accra and Cape Coast vigorously debated the meaning of race and the colonial state’s racist practices. Indeed, colonial era Africa-run newspapers are replete with African critiques of racism and colonial rule in general.

Pierre’s neglect of this history leads her to overstate the power that Europeans exercised. Outside of urban areas, where far fewer Africans lived, until the closing decade of British rule colonial administrators had mixed success in their efforts to assert control over the Africans that they counted as colonial subjects. Moreover, the chiefs through whom administrators sought to incorporate local societies within the empire were frequently overthrown, undermined, and/or ignored by their so-called subjects.

In short, local individuals and groups under colonial rule exercised far more control over how they defined themselves and their political environment than such terms as colonial rule, white supremacy, and subject imply.

It is important that we do not silence the agency that Africans — commoners, royals, and employees of the colonial state — exercised in day-to-day affairs lest we foreclose on the possible meanings of racialized power and its limits.

My reading of Pierre’s book prompted me to imagine new directions for thinking about blackness, difference, and power in Ghana. Without a doubt, racialization on its coast bares both the silent and more palpable imprints of “Whiteness” and the legacies of European colonial rule. However, there is a different picture in the country’s north. Northerners commonly speak of the lighter brown skin of many Fulani as attractive for reasons not related to colonialism or white supremacy. Considering the differing north-south dynamic in Ghana and elsewhere on the continent calls upon us to explore how we might push beyond privileging the coast and Europeans to frame our understanding of Ghanaian and West African conceptions of race, power, beauty, and Blackness. To what extent does northern Ghana’s more Sahelian cultural and political orientation offer a counter or alternative paradigm for the West’s imprint on the coast?

Pierre is the exception among anthropologists in forcefully tackling a comprehensive study of race in Ghana. As more anthropologists follow her lead, the rich historical scholarship on race — in its myriad iterations — in Africa will enliven their work. One example is A Different Shade of Colonialism, in which Eve Trout Powell masterfully illuminates the confluence of European and Egyptian colonial projects in Sudan and the consequences for Sudanese articulations of power, ethnicity and racial difference. In Past Times and Politics by Laura Faire, local conceptions of race, particularly blackness, define the social status of the enslaved and their descendants in Zanzibari society. In a less direct, but still noteworthy manner, in Native Sons Greg Mann unpacks the intersection of conceptions of race, citizenship, and nation in post-World War II Mali. Most recently, Jonathan Glassman’s magisterial War of Words, War of Stones: Racial Thought and Colonial Violence in Colonial Zanzibar centres African and Indian Ocean derived meanings of race and racial difference for understanding relations among individual and groups of Africans on the Swahili Coast during the European colonial period. These are mere samples from a dynamic body of scholarship.

Notwithstanding its limited historical and cultural context and geographic scope, Jemima Pierre’s book is a welcome addition to an important field within African and African diaspora studies. It sheds new and important light on the contours and limits of European imperial power in Africa, and demonstrates the challenges of upholding social categories in a forever and rapidly changing social and political environment. Most important, Pierre helps deepen our understanding of confluence of race and power as a global phenomenon.

*) Pierre’s extensive travel to Ghana, particularly her stays in Accra and Cape Coast add inimitable richness in narrative, but also heavily supplements the clarity of Ghanaian identity formation around diaspora politics. Pierre’s use of the terms “Racecraft” and “racial projects” establish a point of departure in looking at the racialization process; “Racecraft” and its projects capture “the building blocks of racialization processes (racial formation)” by giving meaning to racial formation.

*) Ghanaian linguistic utilizations of “obruni” also help to structure a linguistic and ideological meaning of race as colloquial understanding of class and culture. Chapters one, two, six and seven are theoretical and historical chapters that engage the academic disciplines of the African diaspora. Particularly framed in the first and last chapter is the isolation between these disciplines in order to “challenge the systematic isolation of slavery and colonialism. It efforts to demonstrate that racialization is part of a larger historical act that continues to shape identity and communities on both sides of the Atlantic.”

*) Chapter one departs from the discussion of colonial ruling and the effects of indirect rule in its establishment of generic and naturalized practice of apartheid. Chapters two and six then frame this historical implication into a modern, postcolonial and highly politicized Ghana. This attempt to dismantle the colonial “racial project” clashes with agendas of independence and further racializes all societal aspects of Ghanaian imagination. To Pierre’s attesting point, these racial constructions are again facilitated by hegemonic powers of White Supremacy, informing mutual and often times inaccurate identifications among and between global black populations.

*) Chapters three, four and five “focus on particular racial projects and on distinct sites of Ghanaian racial formation.”

*) Each chapter provides salient examples further demonstrating continued pervasiveness of race in Africa. Chapter three offers countless examples of “white merit” (and therefore power) that remain in Ghanaian society, with no interrogation for justification.

*) The positioning of Whiteness in Ghana and its historical-structural links to privilege highlights Ghanaian societal contradiction. This quest for identity in a highly touted, proud, nationalist country is captured in chapter four’s discussion of skin bleaching. Chapter four further highlights the country’s historically complex relation of race by relevantly connecting the relationship of race explicitly to colour; this colour association is framed in connection to the greater diasporic community. Pierre then examines the Ghanaian state and its political interaction with the diaspora through a contentious scheme of tourism. Again, “Racecraft” is used here to analyze the state’s complex political dynamics. One may be skeptical at Pierre’s decision to focus the political integrity of Ghana through an analysis of two contrasting celebratory events (PANAFEST and Emancipation Day), but again, such examples provide a distinctive analysis of a unique structuring of racial formations in this area. Pierre’s intricate knowledge of a racialized Ghanaian space and its unyielding connection to diasporic studies provides a necessary and enriching analysis of racial formations. Each chapter in The Predicament of Blackness fulfills its objectives clearly and is sprinkled with (at times) humorous, yet relatable experiences of tropes, in a neglected space of dialogue. Perhaps some readers may find Pierre’s seemingly loose form of methodology remiss, but there can be no question to the desperately needed contribution of a theoretical departure point for studies of race in contemporary African societies.

Jemima Pierre, a Sociocultural anthropologist and associate professor at UCLA, employs a more global understanding of race relations in her assessment and examines what a system of global anti-blackness means for Africa. Her work intentionally challenges the idea of Homogeneous Black identity existing on the continent that makes issues of race less pronounced than other Social matters. Pierre grapples with complex issues around a “racialized” Africa in an attempt to identify what it means to be “Black” on the continent. In The Predicament Of Blackness, she uses Ghana as a microcosm for larger phenomenon happening across Africa, covering a range of topics from the prevalence of skin bleaching to concept of whiteness in the country originating from it’s colonial past.

6) MAGEMA FUZE: THE MAKINGS OF A KHOLWA INTELLECTUAL by Hlonipha Mokoena

This fascinating micro-history tackles the lasting legacy of cultural imperialism in South Africa and what it meant for Zulu culture and identity. South African author Hlonipha Mokoena introduces unfamiliar readers to the forming of the “Kholwa Intellectual” who were the first-generation Christian converts often caught in a bind between being fully assimilated into colonial culture and holding on to Zulu traditions.

She does this through the story of the Kholwa author and historian Magema Fuze who wrote his first book written in the Zulu Language by a native speaker Abantu Abamnyama Lapa Bavela Ngakona (1992) which was translated to English in 1979 ( The Black People and Whence They Came). The seminal book was somewhat of a love letter to Zulu identity, which Fuze hoped would resonate deeply with his people.

SOUTH AFRICA: Magema Magwaza Fuze (c. 1840–1922) was the author of Abantu Abamnyama Lapa Bavela Ngakona (The Black People and Whence They Came), the first book in the Zulu language published by a native speaker of the language).

Born in Zululand, he was brought up from about 12 years of age by Bishop John William Colenso, the first Bishop of Natal, and converted to Christianity. Following his education at the mission, he trained as a printer and compositor on Colenso’s press before starting his own printing business. He wrote for a number of Zulu newspapers and in 1896 travelled to the island of Saint Helena to be the secretary to Dinuzulu ka Cetshwayo, king of the Zulus, returning to Natal in 1898.

Abantu Abamnyama was published in 1922 and in an English translation in 1979. It has been described as one of the principal sources of Zulu history.

Magema Magwaza Fuze was born near present day Pietermaritzburg in Zululand around 1840 to Magwaza, son of Matomela, son of Thoko. The amaFuze were a sub-clan of the amaNgcobo. Nothing is known of his mother. His birth name was Manawami, but he was given the nickname Skelemu, derived from the Afrikaans word skelm for rascal or trickster. He told his parents that he would not be raised at home but would work for an important white man.

His year of birth was estimated by Colenso on the basis that Fuze was about 12 years old when he first met him. Colenso converted him to Christianity and baptised him in 1859, giving him the Zulu name Magema. Colenso never gave his converts English or Biblical names. He was educated at the Ekukhanyeni (“place of enlightenment”) mission station.

Fuze was writing in Zulu from a young age and chose to write only in that language. His first piece was an essay describing the daily activities at Ekukhanyeni. Another early piece was an account of day to day dialogue in Zulu, Amazwi Abantu (The People’s Voices). He first appeared in print in J. W. Colenso’s, Three Native Accounts (1860) telling his experience of Colenso’s visit to King Mpande in 1859.

He printed Bibles using the press at Ekukhanyeni during Colenso’s trips to England, and eventually set up his own printing business in Pietermaritzburg. His account of his solo visit to Zululand in 1877 was published in MacMillan’s Magazine in 1878 as “A Visit to King Ketshwayo”. He also wrote letters to and articles for newspapers such as Ilanga lase Natal and Ipepo Lo Hlanga.

In 1896 he travelled to the island of Saint Helena to be the secretary to Dinuzulu ka Cetshwayo, king of the Zulus, who was in exile on the island after leading a rebellion. While on the island he entered into a correspondence with Alice Werner of the School of Oriental Studies. He returned to Natal with Dinuzulu on the SS Umbilo, early in 1898.

Some time after 1900 Fuze wrote Abantu Abamnyama Lapa Bavela Ngakona at the request of the readers of his journalism, but it was not immediately published due to lack of money. It was published privately in 1922, making Fuze the first native Zulu-speaker to publish a book in the language. It was reviewed by Alice Werner in the Journal of the African Society, one of the few reviews given to it at the time, but not until 1931. It was published in English in 1979 by the University of Natal Press in the Killie Campbell Africana Library as The Black People and Whence They Came: A Zulu View in a translation by Harry Camp Lugg edited by professor Trevor Cope.

Hlonipha Mokoena of the University of the Witwatersrand describes the book as significant not just for its use of the Zulu language and its historical content which makes it one of the principal sources of Zulu history, but as an example of the work of one of the group of mission-educated converts to Christianity known in South Africa as the amakhowla (believers) who marked the transition from an oral tradition to a literate culture.

Fuze died in 1922.

A selection of his papers is held in the Campbell Collections of the University of KwaZulu-Natal. In 2011, he was the subject of a biography, Magema Fuze: The Making of a Kholwa Intellectual, by Hlonipha Mokoena published by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

“Writing as an aspirant historian, Magema Fuze’s literary life represents a black intellectual tradition whose potential was not realized”, reads part of a summary via Barnes & Noble.

“Beyond his work as a printer and scribe it is worth adding another role, namely that Fuze was a popular historian, who attempted to write histories whose intimate resonances would not only appeal to his readers but also rouse their nationalistic sentiments”.

7) A SHORT HISTORY OF CHINUA ACHEBE’S “THINGS FALL APART” by Dr. Terri Ochiagha

“Things Fall Apart” is one of the seminal texts of African literature. It holds a unique place in the collective memory of many young people as it’s one of the few books by am African author that is commonly taught as part of the Western curriculum. Sixty years after its debut, it is still being taught, infact it is the most read African novel of all time.

https://www.podbean.com/ep/pb-xb6eg-fd4d14

Chinua Achebe

Despite it’s lasting significance and immerse critical value, there hasn’t been a recent analysis or historical take on the book that goes beyond the typical literary themes to highlight it’s unique role in the broader culture of African Storytelling. This is where A Short film of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart by London–Based Scholar and author Terri Ochiagha comes in. The book, which is her second dealing with Achebe’s work, offers a refreshing critical lens to examine the canonical novel and it’s role in both shaping and transforming African Literature on an international scale- all in one notably straightforward and concise package.