From inter-generational tales to poetic explorations and incisive social critiques, these books present insightful stories that captures the diverse and dynamic realities of South African Women today.

In the ever existing cultures and traditions of the African culture, Southern African Countries[majorly South Africa] do dedicate the MONTH OF AUGUST/SEPTEMBER to celebrating the strength and resilience of women in South Africa, and it is therefore an ideal time to highlight the remarkable books by women authors in this selection that not only honors South African Women’s Month, but also showcases the powerful voices shaping SOUTH AFRICAN LITERATURE, voices that explores themes of identity, resistance and empowerment in a world that often Challenges that narratives.

These inciteful and powerful books by Black South African womenwriters offers a compelling lens on Black women’s complex realities and triumphs in today’s world.

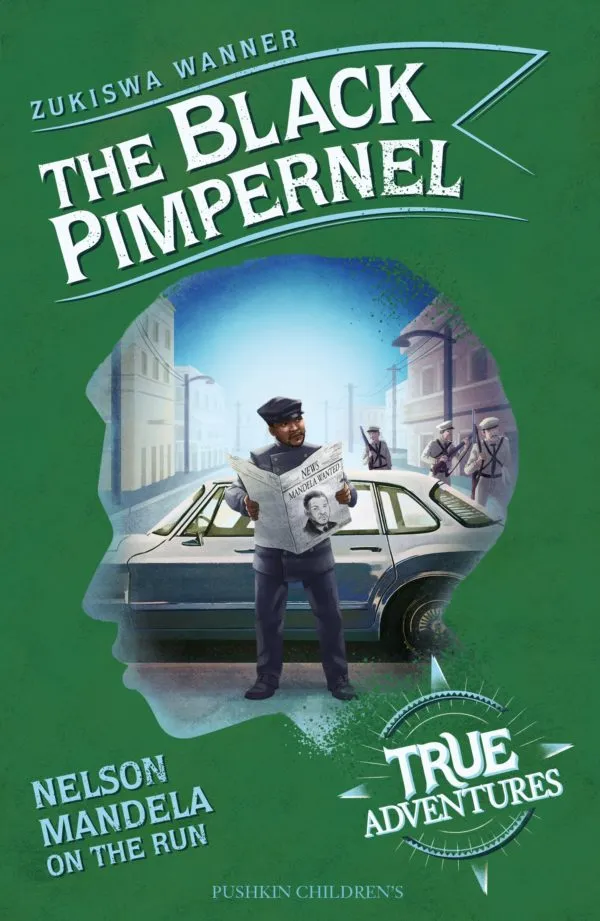

1) ‘THE BLACK PIMPERNEL: NELSON MANDELA ON THE RUN’ by Zukiswa Wanner (Published 2022)

One of the foremost South African prominent writer Zukiswa Wanner returns with this notable account of Apartheid South Africa in her fourth children’s book, after “Jama loves Banana” in 2011, “Refilwe: An African Reimagining of Rapunzel” in 2014, and “Africa: A True Book” in 2019. Wanner’s father was a political exile and one of 1the early recruits in uMkhonto we Sizwe, the military wing that Nelson Mandela setup, and which is the subject of these book that chronicles Nelson Mandela’s clandestine period of evading capture by the apartheid regime. “The Black Pimpernel” illuminates his strategic maneuvers, clever disguises, and the vital support network that sheltered him as he orchestrated resistance. Through her portrayal of the peril and tension of Apartheid South Africa, Mandela’s bravery and the wider struggle for South Africa’s freedom is brilliantly brought to light.

The story of Nelson Mandela’s early years on the run from the apartheid authorities

JOHANNESBURG. MARCH 1961.

Thirty-one activists are on trial for treason. Among their number is Nelson Mandela, a rising star of the resistance movement and one of the biggest threats to the South African government and their racist system of apartheid. To everyone’s surprise, they are found not guilty. But rather than relish his newfound freedom, Nelson disappears.

With this, the incredible true story of Nelson Mandela’s life on the run begins. For months, he is an outlaw, the police and secret services hunting him in vain, living under new identities and separated from his young family. His mission? To set up armed resistance to apartheid, and in doing so change the course of history.

In March 1961, after giving a brief speech at a conference, Nelson Mandela vanished.

For the next eighteen months he was an outlaw, living under assumed identities and in various disguises (sometimes as a chauffeur, sometimes a gardener) as the South African police and secret services, helped by MI5 and the CIA, sought him in vain. His mission? To undergo military training and set up armed resistance to apartheid.

a chapter book by Zukiswa Wanner with captivating black and white, comic book style illustrations by Amerigo Pinelli. This is the latest installment of the publisher’s True Adventures series of historical fiction for ages 8-12.

For those who don’t know the anti-apartheid struggle icon, perhaps you’ve heard of Mandela Day, 67 Minutes or the freedom fighter who was imprisoned for 27 years and awarded the Nobel Peace Prize upon his release? This year, our great ancestor would have turned 103 years old. Every year on July 18th, his birthday, people all over the world are encouraged to follow his example by engaging in good deeds for a minimum of 67 minutes; one minute for every year of his life of service.

Joining the African National Congress (ANC) in 1943, Mandela became South Africa’s first democratically-elected president in 1994 and retired from public life in 2010. He dedicated 67 years of his life to advancing the South African notion of non-racialism and an equal world for all. Non-racialism means the rejection of race as a scientific fact in opposition to Apartheid ideology which believed in upholding white supremacy in every facet of life.

Wanner, who was recently awarded the Goethe Medal by the German government for “outstanding service…for international cultural relations”, previously co-authored a Nelson Mandela biography/photography book for adults and has now expertly transformed a slice of Mandela’s life on the run into a gripping story of suspense and endurance for young readers.

In The Black Pimpernel, Wanner presents the story of Nelson Mandela as one of the ANC’s leaders as well as a loving father and committed husband to Winnie Nomzamo Madikizela-Mandela. She shows how Mandela’s family and comrades provided him with the strength to continue with his efforts to liberate the country at a time when the Apartheid police were baying for his blood and the public was losing faith in the principle of non-violence amidst unrelenting state brutality. Readers follow Mandela’s adventures in the early 1960s as the ANC compels him to go underground and establish military resistance against the state, making him the most wanted man in Apartheid South Africa. Wanner explains how this period earned him the nickname that is also the title of the book:

These same newspapers have now given him the name the Black Pimpernel, after the fictional hero of Baroness Orczy’s novel, The Scarlet Pimpernel. It amuses Nelson as much as it annoys him. Therein lies the racism of this country, even among newspapers that consider themselves liberal. To them, he can’t just be Nelson Mandela of South Africa. He has to be a black version of something white for them to make sense of it. Of him.

With the topic of racial inequality being the great subtext of the book, Wanner is able to guide the reader in and out of the minds of both black and white characters with much empathy, showing the complexities of being differently situated in a racially segregated South Africa. One can feel the pressure that Sergeant Vorster is under; the white policeman must answer to his powerful uncle for constantly being outwitted by Mandela. One can also feel some admiration for Sergeant Maxwell Levy Marwa, a black policeman who would ordinarily be regarded as a traitor for collaborating with the state. Here, Wanner humanizes him and allows him some flickers of heroism.

The Black Pimpernel is divided into 14 chapters plus exciting back matter consisting of an epilogue, a historical timeline, a section titled “a little more about Nelson Mandela’s world” elaborating on South Africanisms, a glossary and additional resources for educators.

The informative book delivers an impactful adventure story and highlights the ideals of equality and justice at the heart of Mandela’s mission: “His children, all children, are too beautiful to grow up in an abnormal society like this one. He doesn’t know whether he will ever be able to secure their freedom but he will die fighting to do so.”

Reviews

Wanner has now expertly transformed a slice of Mandela’s life on the run into a gripping story of suspense and endurance for young readers

WorldKidLit

**- Praise for the True Adventures series

**

Cracking illustrations, true life stories in the vein of the ladybird books but more substantial … brilliantly written by proper writers

Frank Cottrell-Boyce

A South African writer of children’s and adult’s books, Zukiswa Wanner was one of the recipients of the Goethe medal in 2020, making her the first African woman to win this award. Her latest children’s book is Africa: A True Book, a journey though the history, geography and contemporary culture of the continent. She has written for the Observer (UK), New York Times, Mail and Guardian (SA), The Nation (Kenya) and New African.

2) ‘BLACK RACIST BITCH: HOW SOCIAL MEDIA REVEALS SOUTH AFRICA’s UNFINISHED WORK ON RACE’ by THANDIWE NTSHINGA (Published 2023)

Ntshinga, a notable astute female social researcher, media and communications professional, who is a master degree holder in Cultural Anthropology and has studied critical witnesses for almost 8 years. In “Black Racist Bitch”– a titled inspired by one of the earliest comments she received on social media when she shared the research and findings from her book, Ntshinga “pokes holes in the belief that leaving whiteness undisturbed for analysis creates justice and normalcy.

Instead, she says perpetually studying the “other” hinders our development.” Ntshinga argues that critical whiteness studies, an extension of critical race theory, is urgently needed in South Africa. BLACK RACIST BITCH brilliantly challenges the notion that whiteness can remain unexamined, and is a must-read for those who care for and are deeply concerned with the intersections of Blackness and Identity.

Black Racist Bitch captures much of the foetid squalling of the world’s comments sections, an endless dialogue of vomited opinions spewed by dim-wittedly unhearing white people. Whether there need be quite so much of it in this slim book when it isn’t clear if this is the focal point of the narrative is debatable. It should certainly be no surprise that racist white people are systemically invested in not seeing their racism everywhere they go, including the virtual world. But Ntshinga’s argument is of course a more complex one, namely that the relentlessness of it demonstrates just how little was conceded, and how even that concession is stolen back shamelessly as whiteness continues to privilege and embolden its own.

The willed inability to see oneself as acting, and being acted upon by, race—one way in which we might define whiteness as a social concept—has a history of critical study in this country, among which Thandiwe Ntshinga’s potently ungoverned book Black Racist Bitch numbers as a new entrant. The work of understanding whiteness and its effects on the world is important, yet it is often regarded with scepticism and impatience by critics (invariably white), who argue that it recentres whiteness, or that it essentialises identity (a lazy argument). Certainly, the vogueish self-reflexive thinking exemplified by white scholars from Antjie Krog and Leon de Kock to Melissa Steyn, who wrote incisively on whiteness two decades ago, has largely fallen away in the South African social science vanguard, even as it has continued to be the focus point of trenchant work by public-facing writers such as Sisonke Msimang, Angelo Fick and the late Eusebius McKaiser.

A cornerstone of Ntshinga’s argument in Black Racist Bitch is that critical whiteness studies is an under-examined field. This is true, in as much as contemporary whiteness is not simply a lingering aftertaste of past privilege. There is much to show that contemporary whiteness reifies itself in virulently toxic new ways that many white people are disinclined to engage robustly. Witness the prevalent nastiness that infects the white body politic: the Helen Zilles, Steve Hofmeyrs, and Afriforum Jeug—mediocrities all—are merely the weepy crust of a general festering. Ntshinga’s book seeks to understand something about whiteness and those who benefit from it, ‘the white South Africans who are always complaining about a societal decay with the strategic purpose of legitimising white governance as well as garnering intellectual and moral support for white domination’. As a graduate of three of the country’s prominent historically white universities, Ntshinga’s academic preoccupation has been white impoverishment, the so-called ‘poor whites’, and their fraught relation to the mythology of whiteness.

Ntshinga begins this punchy tome by outlining what brought her to social anthropology: as a middle-class queer Black womxn, to be interested in the habits and mores of white people is an unusual research area. Yet Black Racist Bitch suggests that there is something instructive to be gained in looking at that which resists being looked at. Clocking in at 178 pages, Ntshinga’s book is a shaggy dog of theory, historical contextualization and memoir narrative, by turns untidy and compellingly propulsive. It’s a work composed to the beat of digital media, and this is both a strength and a weakness.

Its weaknesses, simply expressed, are a digressive formlessness, a peripatetic musing that never settles long enough for the reader to find their footing. In one section, we move from the author’s time at various historically white universities (helpful for contextualising the interest in whiteness), to a discussion of ‘transnational interracial queer dating’, alighting there very briefly before moving on to the kindred subject of being friends with white people (also a subject that perhaps merits longer discussion than the desultorily anecdotal treatment it receives here). Time and again, the reader encounters a bracingly lucid passage, a thought that begs following, only for the trail to peter out in an unfamiliar thicket.

For instance, at one point in the book, there is a disquisition on South Africa’s history of raced relations that parses where elucidation is called for, rehearses the tenets of Patric Tariq Mellet’s The Lie of 1652 (an excellent work, stitched in here to no great benefit), and somehow manages to make several unfortunately reductive and anachronistically awful points about ‘coloured identity’. The line of argument is too often below the book’s waterline, leaving the reader to speculate haplessly on what might tie several interesting but ultimately disjointed tranches of narrative together, beyond their anecdotal interest.

SHOULD WE CALL THIS LATEST INFORMATIVE VIDEO BELOW A COMIC RELIEF!!!!!!!!!!

3) ‘INNARDS’ by MAGOGODI OAMPHELA MAKHENE (Published 2023)

Described as a “stunning Sowetan debut” by The Guardian, and by Kirkus Review as, “to read Makhene is to understand Apartheid as a live, unhealed wound,” Makhene’s debut, a collection of interlinked short stories that touches on Violence, Apartheid and colonization, follows the everyday lives of people living in suburban Soweto; an unrepentant, fake PhD; a girl who loses her voice after watching a human being burned alive; a woman reeling from the aftermath of police brutality, and a pair of twins embroiled in a fierce rivalry.

On the front cover of the South African writer Magogodi oaMphela Makhene’s impressive debut collection of linked stories about life under and after apartheid, a young Black girl, primly attired in a collared dress, holds in each of her hands a chicken – defeathered and seemingly gutted. Look closer and you’ll notice the horns on the girl’s forehead and a sinuous stream of blood down her left leg. Her eyes stare ahead, whether in resignation or pain or provocation. Makhene’s book, like this image – an oil painting by Zimbabwean artist Kudzanai-Violet Hwami – melds the ordinary and the spectacular, grief, grit and horror, in novel and arresting ways.

Makhene concocts her grim tales with the right blend of history and story. Political exposition comes in slivers of dialogue, action and scenery; you must work to grasp her cues and references. Her stories – soaked in the languages of Soweto (isiZulu, Sesotho, Sepedi, Setswana, Afrikaans) and studded with important facts, names, dates and local political lore – often seem like a challenge to the unversed reader. “Can you move over to where I am?” she seems to ask, in the manner of Toni Morrison. Do you care to fully inhabit the world and worldview of my characters?

This incendiary debut of linked stories narrates the everyday lives of Soweto residents, from the early years of apartheid to its dissolution and beyond.

‘A gut punch of a collection…it astonishes as it reveals how malignant political forces can both ravage and vitalize the human spirit.’

In her stories, Makhene pays homage to her roots, blending Afrikaan and South African English into her prose. Through the lives of her characters, she challenges us to confront the harsh realities and enduring impact of violence. Innards offer a raw and heartfelt portrayal of Black South Africa, and cements Makhene as a relevant voice in contemporary fiction scene.

In 7678B Old Potchefstroom Road, Ethel’s reunion with her brother Kingsley is complicated by the pass laws in place. Arriving at Ethel’s place from Transkei, one of the two independent “homelands” or “Bantustans” designated for the Xhosa people during apartheid, Kingsley has to hide in the coal bin during “dompass” raids at night. Kingsley “still hadn’t found work. Which meant he had no white man to sign his papers. Which made Kingsley the thing they stamp in a dompass before deportation: ‘Prohibited Alien.’” Later, when Ethel’s husband dies, his papers prove insufficient to prevent her repatriation to Transkei. Soldiers mercilessly ransack her house, and throw all her furniture out.

Children feature in several heart-wrenching stories. In Star-Coloured Tears, a young boy returns home from a fishing trip with friends to find that his mother, an anti-apartheid activist, has been taken away by the police. In The Caretaker, a mother and her children are made to witness the killing of their dog at the hands of a Boer policeman. In Black Christmas, an 11-year-old schoolgirl stops speaking after she comes across a Black man being “necklaced” or burned alive for his suspected collusion with apartheid forces. Another thread of the story concerns the girl’s schooling within the strictures of the Bantu Education Act, dramatising clearly and forcefully how apartheid sought to induct Black South Africans into a life of subservience and manual labour.

In the title story, a man begins to relive painful episodes from his past after receiving the news of his father’s death. Now living in Berlin, he recalls witnessing, as a child, his father’s “servile nakedness” as the police paraded him through the streets. He remembers the raids, how “all the fathers and grandfathers and uncles and brothers” were rounded up, “shaken like loose litter from their houses”. Meanwhile, his sister, settled in New York, is haunted by the image of the mutilated body of Steve Biko, the anti-apartheid martyr whose funeral she had attended. “She remembers seeing his sunken eyes lying in his coffin. Neck snapped into chicken bones. Broken wing bones, clavicle, keel, rib. Broken lip too false to form any word you’d recognise as human.” To read Makhene is to understand apartheid as a live, unhealed wound. It is to contend with and comprehend, deeply, intimately, the savage realities her characters endure, and the unconquerable memories of violence that they carry. This makes for an extraordinary achievement.

Set in Soweto, the urban heartland of South Africa, Innards tells the intimate stories of everyday black folks processing the savagery of apartheid. Rich with the thrilling textures of township language and life, it braids the voices and perspectives of an indelible cast of characters into a breathtaking collection flush with forgiveness, rage, ugliness and beauty. Meet a fake PhD and ex-freedom fighter who remains unbothered by his own duplicity, a girl who goes mute after stumbling upon a burning body, twin siblings nursing a scorching feud, and a woman unravelling under the weight of a brutal encounter with the police. At the heart of this collection – of deceit and ambition, appalling violence and transcendent love – is the story of slavery, colonization and apartheid – and it shows in intimate detail how South Africans must navigate both the shadows of the recent past and the uncertain opportunities of the promised land.

Full to bursting with life, in all its complexities and vagaries, Innards is an uncompromising depiction of black South Africa. Visceral and tender, it heralds the arrival of a major new voice in contemporary fiction.

ZA: I would love to start from the very beginning. How did you get interested in the world of languages and literature? When was the seed planted for you? What captured your interest at that stage?

MoM: The stories people carry —especially the stories that only come out in hushed tones and long pauses, if at all—have always fascinated me. I’d listen to adults speaking and pick up clues about our burning country and strange words that came up again and again: rape, exile, detention. This nosy business started very young. Writing and being good at it also came early. But I didn’t understand it as a gift until much, much later. I got serious about writing at 30.

ZA: I appreciate how this proves that there really isn’t a timeline to follow and everybody can find their own path. This also segues nicely into my next question, when did you go from writer to aspiring author? From being nominated for the Caine Prize in 2017 to releasing your debut collection, what did that journey look like for you?

MoM: I’m not sure there’s much of a distinction between writer and author, apart from the weight of a bound book in hand or what the ego craves to validate a sacred practice — which is its own reward. Sure, I went to writing school and got Innards published, but I didn’t think of myself as an aspiring anything. Always, always, I am first a writer— I’m most nourished by the practice of my craft.

Practically speaking, my personal recipe for publication included a nice and healthy heaping of depression, a daily dose of sentences that didn’t start with much ambition beyond self-medication and eventually, a small but strong serving of stories which I submitted, without much expectation, to grad schools. When Samantha Lan Chang called to invite me to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, I thought it was a lousy prank. And then, the gift: two years stuck between America’s cornstalks, focusing my mind on the craft, community and devotion writing takes. I learned that every sentence can be a prayer. That every word can be its own song.

ZA: It seems you have always been enamored by the short story form. What does the short story mean to you? Who are some of your personal favorite short story writers?

MoM: I’m very interested in how the oral tradition continues, as literature, in the modern African experience. To me, listening to my late uncle animatedly describe what it was like to experience television for the first time—as a caddy for elite white golfers during apartheid, before TVs became widely available to black South Africa—that is a powerful form of short story. These are the inner lives I wanted to explore through writing Innards.

In Western tradition, I’m drawn to writers who make you feel you’ve just dropped into someone’s unfiltered mess, midstream. George Saunders comes to mind. Or the singular and angular drive in a story like A Good Man Is Hard to Find/Flanery O’Conor. Sidik Fofana’s The Tenants Downstairs is just stupid it’s so sublime. I fan girl HARD for that book. Junot Diaz’ Drown was seminal. He made me see myself as a writer. I could eat every sentence and feel full and fueled enough to imagine my own inner writing world. Always, always, his work STAYS with me.

ZA: I am updating my reading list right now! Now, let’s talk about the stories in Innards. They are beautiful, nuanced and poetic. What was the inspiration behind this collection? How did you choose the topics to write about? How did the stories come together?

MoM: Thank you—appreciate your reading the book!

Soweto, my world as a girl coming into life during apartheid South Africa, is the center spine of Innards. I wanted to make sense of the mind fuckery of what we’d lived through as a collective—at the granular level of body and being. And I wanted to explore that through our innermost thoughts, prayers and sins. Innards gets under the skin of human experience, outside the white gaze. I wanted to know who and what we are and were and may become, on our own terms, when we aren’t performing blackness.

ZA: That is so beautiful. You also run an advocacy organization called Love As A Kind of Cure. Can you talk a bit about your work there and how it relates to your fiction writing? How do you use art for activism?

MoM: The throughline between Love As A Kind of Cure and my writing life is a devotion to humanity. Yes, there’s the catalytic question of white supremacy, how do you untangle yourself from its tentacles when it’s endemic in the very air we breathe? When, as in my particular case, you’re born into a crime against your very humanity; which by the way, is how the UN categorized apartheid. Beyond that, there’s imagining and then being bold enough to embody liberation. A dangerous and audacious ambition that demands every fiber of soft muscle inside skin.

My company is about creating experiences that help people imagine and embody freedom. Through a talk, a workshop, an immersive experience or training course infused with art. My writing life, at its best, is practicing how to touch and taste freedom—because writing truth requires so much courage, compassion and humility that you become freer by becoming its disciple. There is no ego in creating a perfectly true sentence. Just as there can be no ego in creating and nurturing a culture where we’re all wildly and fully free.

ZA: That’s a beautiful answer, thank you. In your 2017 interview with Wasafiri, you mentioned some of your unconventional writing habits; writing on old receipts, penciling notes on walls. Has your writing routine changed since then? What does it look like now, and how do you balance it with your other work?

MoM: Lol! I’m laughing because I remember that woman and her midnight scratches on walls, holding onto an idea/dream/thought. I’m not that person today. Midnights are interrupted by baby scratches, from a child with his own unconventional (to us know-all grown ups, lol) habits. So yes, my practice has changed. I’ve slowed down.

Everyone told me that parenting, mothering specifically, would encroach on my writing. That it would compete in a winner takes all game of thrones against my child and I’d be forced to choose between the two. It’s important to be honest about what writing while living a full and demanding life in this black woman body requires.

Here’s the truth: Childcare in America is shit. That’s what’s killing women’s art. Mothering itself is a boon for writing. Especially if you’re daring enough to think outside the capitalist dictates of productivity; if you understand that slowing down can itself yield a miracle. Just think how pregnancy morphs time into a centuries-slow melting glacier. And then, BOOM, life!

ZA: Indeed, there is a pace for everything. Speaking of writing, what does the future look like for you as it relates to further books down the line? What are you working on now, if you can talk about it?

MoM: I’m writing. That’s the win for me—returning to a daily devotion, no matter how far I stray. And also, hitting the stacks like a fiend, studying my craft. More than that, expect a damn good book when I’m done. Yup! I’m woman enough to claim my superpowers.

ZA: Yes, love to hear it! I have one last question before I let you get back to work. If you could give one piece of advice to aspiring authors, what would it be?

MoM: To write, write. People always wanna know if it’s long hand or word processor, if it’s early mornings or midnight oil. The truth is all that really doesn’t matter because it won’t get you a working manuscript. Only writing can do that. Writing is getting up, sitting down and doing the work. So simple yet so hard till you train your brain into habit, like any other muscle.

It’s easier than many people think to become an author. Thousands of books are published every year that don’t make a single tree proud. To publish, write something worthy of the precious life that became pulp to print your pomp and circumstance. I know, I know, I know…I sound all extra, but that’s the dead-ass truth. Stop wasting paper with lame ego-strokes just to see your name on a spine. Make art. I dare you.

Magogodi oaMphela Makhene is a proudly Soweto-made soul, who now makes her home anywhere with sunshine and writing space. An Iowa Writers’ Workshop alum, Magogodi is a Caine Prize, Hedgebrook, MacDowell and Rona Jaffe Award honoree. She leads immersive courses and experiences at Love As A Kind of Cure, a social enterprise she co-founded to dismantle white supremacy.

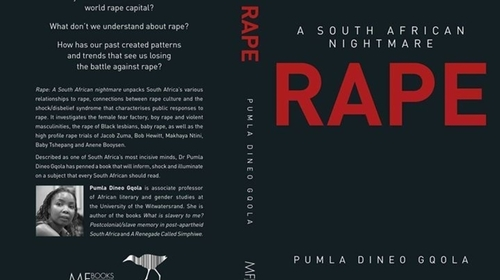

4) ‘RAPE: A SOUTH AFRICAN NIGHTMARE’ by PROFESSOR PUMLA GQOLA (Published 2015)

This book is both brilliant in the way it unpacks the complex relationship that South Africa has with rape and distressing in the way this relationship is seen to unfold in reality. Rape is a scourge that South Africa has not been able to escape for years and the crisis only seems to be worsening. Written almost four years ago, Prof. Gqola’s profound analysis of rape and rape culture as well as autonomy, entitlement and consent is still as relevant today as it was back then – both a literary feat and a tragedy. There can be no single answer to why South Africa is and remains the rape capital of the world, but RAPE: A SOUTH AFRICAN NIGHTMARE, and it’s 2021-follow-up, The Female Fear Factory, is by far one of the best attempts thus far at investigating the intersection of women’s lived experiences and patriarchal society.

The question of why South Africa has such a high rape rate is one that continues to be deeply troubling. It’s just one of the issues tackled by academic Pumla Dineo Gqola in her brilliant and distressing new book Rape: A South African Nightmare.

“I do not remember how old I was when I first became aware of rape as a thing in the world,” writes University of the Witwatersrand associated professor Pumla Dineo Gqola. Most South Africans likely learn about rape, or the threat of rape when they are very young – even if that’s not what they might term it. The prevalence of rape is one of the most alarming elements of South African society: a “nightmare”, as Gqola terms it in her new book’s title.

The notion that rape in South Africa is a specifically post-apartheid problem is deftly dismantled by Gqola. It is natural that rape charge statistics would rise after 1994, she writes, because black women felt more likely to be believed: previously, police stations had been deeply unfriendly places.

“If we are at all serious about making sense of rape’s hold on our society, we need to interrogate the histories of rape in South Africa,” Gqola writes.

She points to the rape and forced impregnation of slave women in Cape society; the fact that rape was a core feature of colonial rule; and that British soldiers at war with the Xhosa are recorded as having committed rape. Under apartheid, no white men were hanged for rape. The only black men who were hanged for rape were convicted of raping white women.

South Africa’s history of violence and dispossession has bred a kind of toxic masculinity which flourishes at both ends of the political spectrum. “Under colonialism and apartheid, adult Africans were designated boys and girls, legally and economically infantilised,” Gqola writes. Asserting masculinity could provide a way of rejecting that position. Both the left and the right in South Africa are prone to hypermasculinity, from the Struggle hero to the gun-toting Afrikaner: rape was perpetrated both by apartheid agents and liberation figures. To this we can add the fact that nation-building narratives, so favoured by South Africa’s post-apartheid governments, tend to be masculinist in nature the world over.

Gqola’s book takes on a number of widespread perceptions about rape, and makes it clear that the problem is a complex one. For example: in the 1980s, it was not uncommon for young black women to be abducted and raped by gangs, which Gqola notes is a complicating factor for the conventional wisdom that most sexual violence is perpetrated by men who know their victims.

]The Chapter 2.12 protests at Rhodes University last month saw outraged students speak out against poor university policies, which inadequately address rape culture and sexual assault on campus. The demonstrations also brought these issues into national dialogues, and saw activists standing up against the reproduction of violent masculinities, the policing of women’s bodies and a broken legal system. A powerful, must read, South African book that continues these conversations is Rape: A South African Nightmare, by Dr Pumla Dineo Gqola, which was recently shortlisted for the Sunday Times Literary Awards. Youlendree Appasamy reviews Gqola’s book, which seeks to redress the lacklustre, lazy, and often downright insensitive and misinformed way that rape and sexual violence is spoken of in South Africa.[/intro]

There are many incidences of sexual aggression perpetrated by violent masculinities and “phallic women” that I have witnessed and been on the receiving end of in my young life. They span nearly every place imaginable – the countryside, the suburbs, the beach, the streets, the clubs, the classroom, the lecture hall, the pool, the bar, the bedroom, the campus, the chatroom, and the comment thread. They were all perpetrated by different people, strangers, friends, peers, lecturers, teachers, and family. These experiences are not unique to my life, it is all too commonplace. To be a young Black woman is to fight relentlessly, the opponents changing as quickly as the environments do. This is not only my story, but is the story of those who have been forced to adhere to the injustice of patriarchy and whose existence ruptures it.

If there was any one text I would suggest in the bag of a warrior, it would be Rape: A South African Nightmare. As the title screams in upper case red lettering, the book deals with rape in South Africa. However, to say the book sticks to that content alone is disingenuous. Gqola, who is a majestic and incisive writer and whose prose is as delicate as it is incendiary, covers a variety of topics ranging from the period of formal slavery to apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa. Like a hot knife through butter, she dismisses smokescreen arguments and gets to the prickly core of gender based violence in South Africa. The book documents histories and a chauvinistic and terrified mode of being that we do not want to see for ourselves. We would rather cloak our fear in apathy, or find a scapegoat, or ignore the problems altogether. Gqola urges us to collectively and bravely look at the sores, wounds and defence mechanisms that have accumulated over the centuries, to rupture the mentalities that perpetuate and allow endemic gender based violence to continue so that we live in a society that matches up with the ideals of the Constitution – our manifesto for freedom.

Who is this book for? Everyone who wants to live in an equitable society, free from violent masculinities and the cult of femininity. No one is too young or too old, too wise or too ignorant. In fact, if you look at the title of the book and put it down thinking that rape is an issue for women and Black women at that, then this book is even more for you.

Gqola’s dual approach of looking at the violent masculinities that perpetrate sexual violence and the cult of femininity that accepts and allows for further violations highlights issues in a new matrix.

The cult of femininity which positions women, female presenting, and gender non-conforming bodies on the frontlines of violence if they overstep certain boundaries and ‘norms’, is particularly interesting.

The phenomenon of baby rape, Gqola writes, is a rebuke both to those who insist that rape is about sex, and to those who maintain that rape survivors ‘invite’ rape in some manner, such as through their manner of dress. She cites research showing that child rapists have backgrounds involving abuse and sexual violence – but then points to cases like that of tennis professional Bob Hewitt, who was convicted of raping two former students. “Child rapists are not monsters, nor are they all necessarily young men from impoverished backgrounds,” she writes. There is no significant difference in profile between rapists who rape adults and those who rape children.

“I cannot accept the lie that poverty makes it more likely for men to rape,” Gqola writes, and her book profiles a number of cases involving wealthy (or relatively well-off) men accused of rape. The manner in which beliefs about rape intersect with racism in South Africa is artfully unpacked by Gqola. In the case of cricketer Makhaya Ntini, who was convicted of rape but successfully appealed, opponents of transformation in sport gleefully leapt upon the case. In all such matters, the focus is invariably on the man accused of rape rather than the woman who says she has been raped.

What Gqola calls the “female fear factory” keeps women silent and biddable. When women confront men who are harassing them in public, often sheer surprise stops the harasser in his tracks. But this requires the woman in question not to be afraid, or to act in spite of her fear.

Crimes like the rape and murder of Anene Booysen communicate a particular message to women: don’t go out at night, don’t go into bars, or that too could happen to you. “Even sports stars are unsafe when they are women,” Gqola writes, referring to the gang-rape and murder of Banyana Banyana midfielder Eudy Simelane.

Government gender initiatives in South Africa are the equivalent of putting lipstick on a pig, she suggests: “This talk of ‘the empowerment of women’, as currently employed and aired in South Africa, rests on the assumption that ensuring that some women have access to wealth, positions in government and corporate office, is enough gender-progressive work for our society.”

It proposes, she notes, that the public space is the only place in which women need to be empowered – ignoring domestic contexts. It does nothing to address the problem of violent masculinities. We need to talk to young boys, Gqola counsels, and pay close attention to the lessons they are absorbing about what a man is and what a woman is.

At the heart of Gqola’s book is the 2006 rape trial of Jacob Zuma, which she returns to repeatedly as emblematic of South Africa’s gender problems in a number of different respects. She described the trial as “a watershed moment for what it highlighted about societal attitudes that had previously been slightly out of view”.

The cult consists of people, mainly women, who make and re-make rules for a strict gender hierarchy. The cult normalises rape culture and continues to dictate the paramaters of safety, freedom, and expression for women. SAPS safety guidelines for women at night come to mind. “Do not stop at a red robot if you are driving late at night by yourself.” “Do not walk home late at night”. “Avoid being drunk and around strangers”. Essentially – follow our guidelines, don’t be a bad girl and you will be safe. Hence, anyone who is violated is seen as outside the bounds – “She deserved it” is still acceptable on the palate for many South Africans. Anene Booysen’s brutal rape is another story that comes to mind. So many think pieces, armchair commentators and mainstream media outlets added to the moral panic of “keeping our women safe,” without examining who make women unsafe and why burdening women with their safety is part of the problem of their un-safety. The female fear factory is one of the key features of the cult of femininity. It operates and is performed and repeated until it becomes invisible in our society. Gqola names and sheds light on how rape threats function in a society where fear is the commodity produced by this factory – female fear especially. Her analysis itself is a disruption to the cogs of the machine as its power lies in its invisibility.

Manhood and masculinity is not violent – it is multilayered and complex. Violent masculinities are a specific performance, a psyche that prioritises a patriarchal manhood. As Gqola notes, “it is effectively manhood on metaphoric steroids”. Kenny Kunene is one of the examples (from the many that Gqola could have chosen in South Africa) which demonstrate how a violent masculinity is often intertwined with ideas of power and money in contemporary South Africa. His comments about gang-rape on twitter, his openness in stating he has had sex with women younger than 16, all allude to society’s unwillingness to confront rapists and hold them accountable. “Kunene understands something the rest of our society often pretends it doesn’t know: that South Africa has a greater problem with the existence of a woman who speaks of having been raped, the young man with a broken body from rape, the old woman maimed and raped, and the child who needs reconstructive surgery than it does with a proud, known rapist,” Gqola says about the issue. Complicity and reproduction of violent masculinities is what makes this manhood a continuing feature in South Africa.

The cult of femininity needs to be shattered, just as much as violent masculinities need to be. Extreme policing of people’s bodies, which is a common thread between the two, is something that is shared with apartheid and slavery. Gqola’s delving into history, in the first two chapters, shows how much gender based violence, sexual aggression and sexual violence of today looks very much like the same systems of domination during South Africa’s history.

Roman Dutch Law, which never once tried a Black or white man for raping Black women during the period of slavery and colonialism sounds familiar to the modern legal system which re-violates and inculcates fear and self-doubt in victim-survivors who choose to take their perpetrators to court. Black women were rendered unrapable due to their position in these systems of domination in the past. Unrapable meaning that if sexual violence is acted upon them, it is not violence enacted on another human being – as black people were seen to be sub-human fetishes. Sex workers follow the same grammar of patriarchy and racism. And yet today, Black women are the most vulnerable to rape in this country and their stories are often met with claims stemming from a racist, sexist psyche which claims that Black women are unrapable. Jacob Zuma’s rape trial stands as the strongest example, on a national, public level, of this oppressive view. Khwezi’s trustworthiness, her story of her rape, her being and humanity was under fire during the trial. How dare she accuse a powerful man, one of the most powerful in South Africa, of rape? Supporters of the status quo denigrated her and her supporters into rabble rousers, opportunists and liars – because in their minds, Black women cannot be raped, especially by a powerful Black man. South African society, feminist scholars and activists did not play ball with patriarchy. Many of us stood behind Khwezi with love and support. Legally, Zuma was acquitted.

Child rape and molestation are also addressed by Gqola. This is another area where the legal sphere comes under fire. There is a “forked tongue” when it comes to child rape, Gqola notes. When instances of child rape are made visible, taken to court and reported on, the reliability of a child’s testimony, the injuries sustained, the motivations and slithery manoeuvres by child molesters and rapists all turn against the child victim-survivor. The credibility of a child victim-survivor is definitely high – the outrage of a child rape such as Baby Tshepang is an example. However, courts in South Africa often minimise the sentences of child rapists, and society’s shock and disavowal of the child rapist (who is often not a hulking monster but a trusted figure) is not matched by the punishment (not to mention, potential rehabilitation measures). The hypocrisy of bystanders and the injustices in this realm are hidden, to a large extent. Children are an auxiliary to the vulnerability of the feminine. Child victim-survivors pay the price of society’s silence on childhood sexuality, bodily autonomy and sexual violence and they end up on the interstice of the forked tongue.

This book is easy to read and difficult to swallow. Gqola holds up the mirror and we must see for ourselves what the image shows. It shows the mother who will turn a blind eye when her child is being molested, it shows the generational violence and trauma from jackrolling, it shows a broken legal system, it shows unsupported victim-survivors, it shows weak state attempts at gender empowerment and importantly, it shows the brave people fighting to interrupt and dismantle systemic and systematic gender based violence in South Africa.

Zuma’s rape charge was laid by a woman known as Khwezi: “A well-known HIV-positive activist, lesbian daughter of Zuma’s late comrade”. Khwezi was forced to leave the country in the wake of the trial due to the backlash against her. Gqola notes that only one book currently exists on the trial, and that she knows of two manuscripts whose publication has been “thwarted”.

Some aspects of Zuma’s trial were deeply typical; others less so due to the high profile of the accused. In the latter category: the swiftness of its resolution; the placement of the rape accuser in witness protection; and the diligent collection of DNA evidence.

More characteristic of South African rape trials was the fact that media overwhelmingly placed the focus of their attention on Zuma rather than the experience of his accuser. Within the trial, Gqola lists troubling elements, such as “the way (Khwezi) spoke about her identity as lesbian, which was dismissed and replaced by another marker of identity as bisexual”. Khwezi’s previous sexual history was also admitted into evidence to frame her as someone whom it would be impossible to rape – a category, Gqola notes earlier in the book, which includes sex workers, wives, slave women and men.

Gqola understandably cannot reach any definitive conclusions about the origins or current causes of South Africa’s rape crisis, but she compellingly details the social conditions which normalise and excuse it. Her book is written with enviable clarity. Academics addressing a wider audience than normal often tend to carry ponderous academic style and jargon along with them; not so in Gqola’s case.

“I wish that I did not have to think about rape, that it was not so close to home, that I did not have to think about the many times I have felt the combination of rage and tenderness as I sat across from someone as they talked about how someone had raped them,” Gqola writes in conclusion. But the South African public is better off for her having done so.

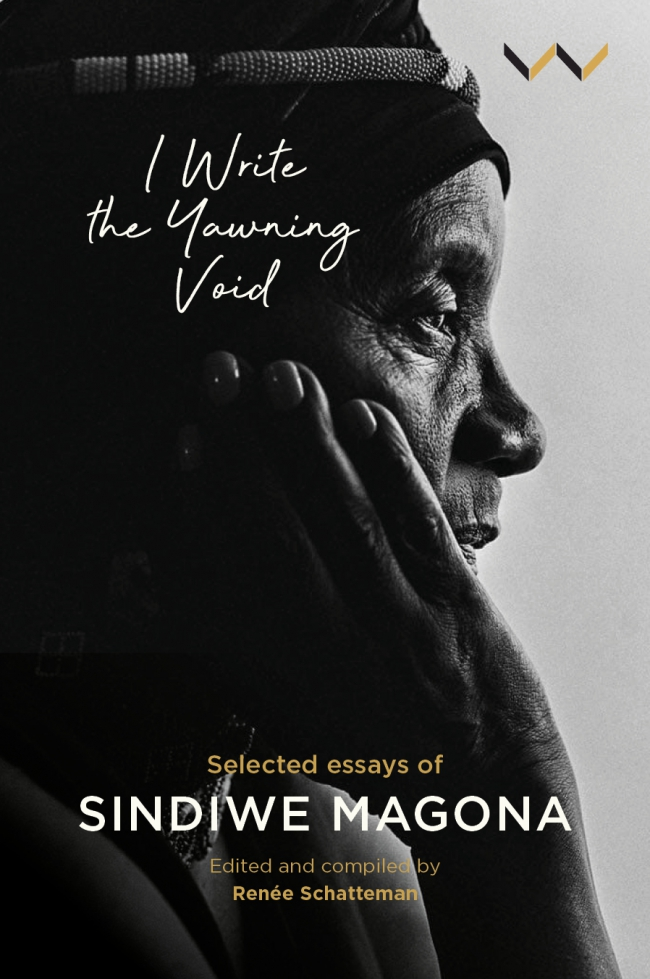

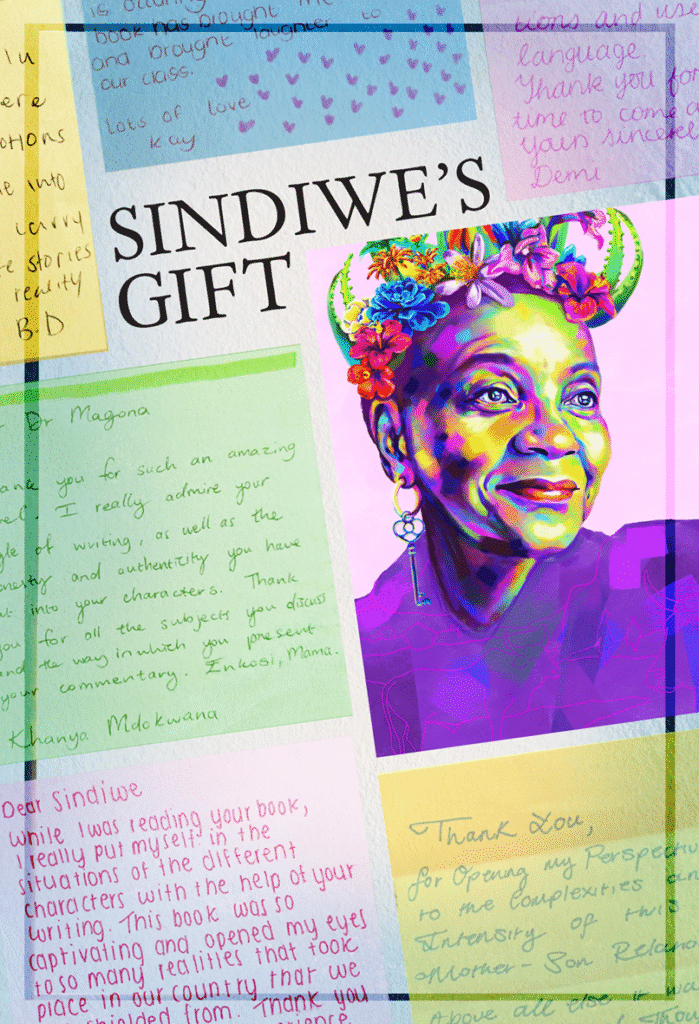

5) ‘I WRITE THE YAWNING VOID’ by SINDIWE MAGONA (Published 2023)

Accomplished author Sindiwe Magona’s written works are inspired by her lived experience of being a Black woman resisting subjugation and poverty. After the triumph of her 2021 novel When The Village Sings, which explored the complexities of poverty, womanhood, humanity and tradition, Magona returned in 2023 with I Write The Yawning Void, a collection of selected essays that “bring to life many facets of Magona’s personal history as well as her deepest convictions, her love for her country and despair at the problems that continue to plague it, and her belief in her ability to activate change.”

Fear of Change

I have seen the thick welted scars

On people rudely plucked from hearth

And home. Bound hand and bleeding foot.

Kicked, punched, raped and ravaged

Every which way you dare to think.

Killed, in their millions and

Dumped on icy wave.And today, those unlucky enough to

Survive the gruesome plunder

Annoy the world by failing to be quite,

Quite human. By falling short of accepted

Standards of civilisation. Never mind that

On these people, was performed a

National Lobotomy, that has left them with

No tongue of their own.

What’s the “yawning void” you refer to?

The void or gap is the invisible but loud and tangible conversation that does not take place in our country. What is stopping us from realising the dream of being the “rainbow nation”, to use Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s now world-famous term? In the heady days of transition to democracy, the stars seemed reachable. When apartheid ended, the dream was that South Africans, coloured all hues of the human palette, would come together and live side by side, sharing all the land gave them.

However, that has not happened and the void boldly stares us in the face. No peaceful coexistence is taking place here. The void is the issues we avoid tackling honestly, courageously, meaningfully and towards amicable resolution.

What are the pressing issues you address?

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission failed to deliver or make possible any true reconciliation, as that is not realisable without restitution.

Structurally, South Africa remains a country of sharp contrast between the rich and the poor, which, as a result of its vicious history, translates to white and black … barring a few newly rich blacks (mostly government personnel or connected to the same). The essays also warn the reader not to rest on her laurels while waiting for social transformation (which has remained an illusion). Agency is the name of the game! All successful people tell us that.

So the key pressing issues I address in this book are the twin mountains we have to climb to find our ubuntu – our true liberation: racialism and poverty. Linked and mutually reinforcing, they give rise to self-hate and vulnerability (such that people can’t or won’t properly take care of themselves or make good choices). The HIV/AIDS pandemic, teen pregnancy, paternal orphanhood are but some of the results of racialism and poverty.

Why the essay form?

I like the essay form for the ease of doing it. The essay, more than all the other art forms, most approximates cordial conversation. For me, writing an essay feels like talking to a friend or colleague. Also, unlike the other forms, it is less restrictive – the writer can go any which way – even contradict herself … as long as that makes sense to her.

The essay approximates storytelling more than the novel or short story. And I love telling stories … Nomabali (Mother of Stories) …

How did you become a writer?

I became a writer by giving motivational talks and getting constant advice: “You should write that! Write a book!” I started out as a primary school teacher, with the lowest qualification possible. But then I lost my job in my first year of working and it took six years before I got rehired as a teacher.

It was during this difficult time – no support from the government, a single parent of three children all under five, excluded from job opportunities – that I resorted to domestic work. Between domestic worker jobs, I also sold skaapkop (sheep head) and vetkoek (fried bread) and ginger beer. Domestic work opened my eyes and I gained some sense of how life was lived on the other side of the railway line. Between that and my sense of shame I eventually got it into my head to change my life. There was only one way I could come up with to do that – education.

I embarked on a course of study, by correspondence, and stumbled on a goldmine – human beings eager to help me make it! The more I studied, the more people I encountered across the apartheid-made boundaries. I came to participate in group dialogues aimed at easing tensions among South Africans … The circle just grew and grew and grew, via word of mouth mostly, although once in a while there would be a write-up in the newspapers or magazines or a radio interview.

But it took years and years for me to gain enough confidence to put pen to paper. I didn’t know I could write a book – never mind many books! Social discussions about who wrote books on whom was the additional goad I needed. It occurred to me that white people writing about black people did not stop black people writing about themselves. If we believe in the oneness of humanity, how can we turn around and say there are limitations to human empathy?

What are the core take-aways from your reflections on your own writing?

The revelation of how uncertain I am at the onset of each writing journey, even now, more than three decades since the publication of my first book.

To any who would be a writer – anyone who thinks or feels they’d like to – I would say, “Go for it! Start!” Sit down and start putting down what comes to you … of course, mindful of where you are headed, what you want to say. No matter how vague it is, have a plan, an idea of what story you are telling. Beginning, middle, end. I still hesitate. But eventually I take a deep in-breath and dive straight down. The lesson is: you’ve got to start, to finish!

All my work shows, I think, how an idea plants itself into my heart and mind. I may mull over it for some time or, not often, I go straight into action as soon as the idea knocks at the doors of my inner being.

I am still learning to believe in the power or gift I have been given. Everyone on earth has talent. Even doubtful Sindiwe Magona eventually woke up to that indisputable fact. May the readers open their eyes much, much sooner than I did. That would spell success, for me. That is why I write … to enable others to more successfully navigate life and its many twists and turns.

A prominent fiction writer who now also commands the essay form, Magona through these selected essays, offers thought-provoking reflections on the issues that inspired her work.

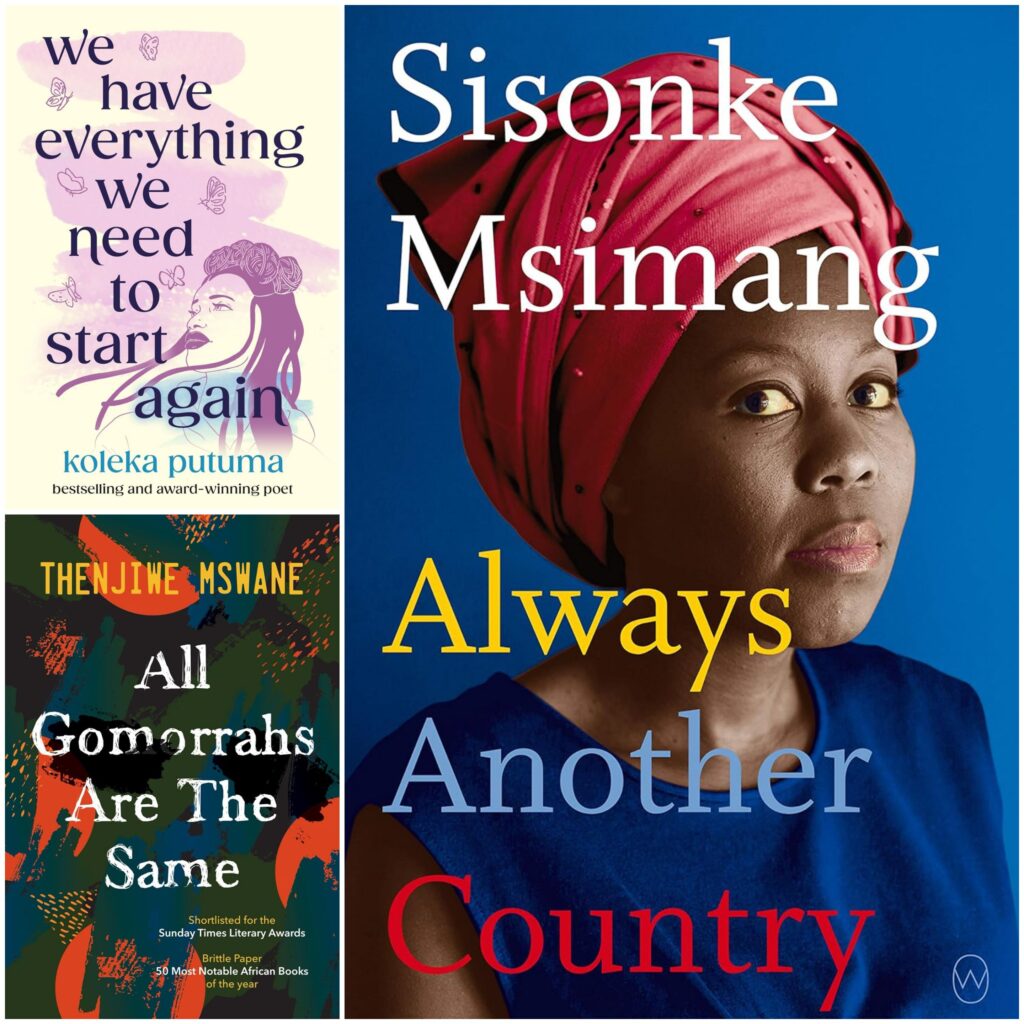

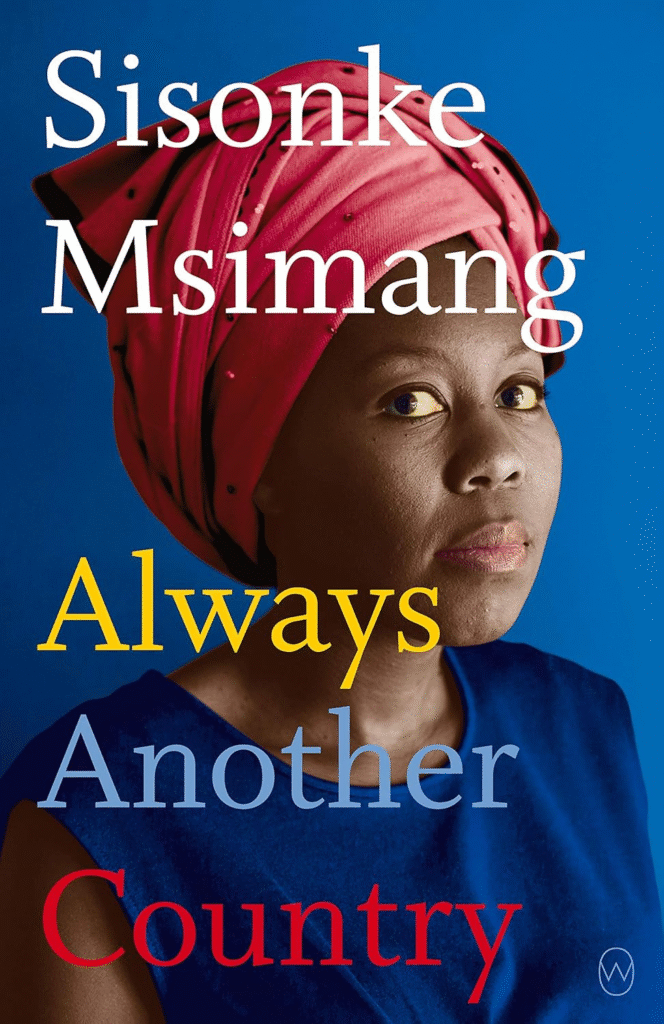

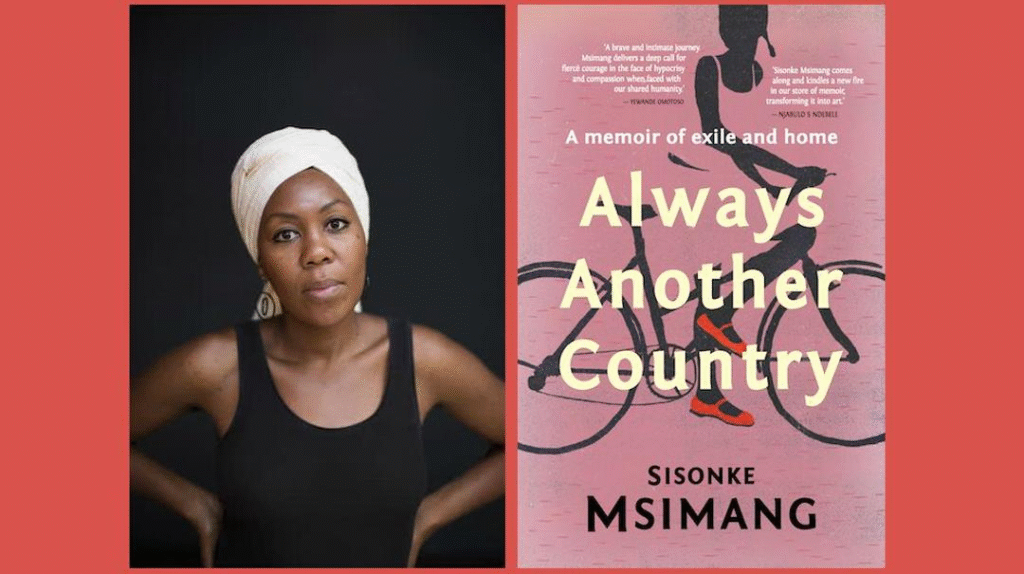

6) ‘ALWAYS ANOTHER COUNTRY’ by SISONKE MSIMANG (Published 2017)

The Synopsis of MSIMANG Memoir details her political awakening while abroad, as well as her return to a South Africa on the cusp of democracy. Hers is not an ordinary account of Apartheid South Africa and its Aftermath but rather a window into yet another side- the life’s of South Africans living in exile and more so, what happens when they eventually returns home. Admittedly, it’s an honest account of class and privilege. Msimang describes the tight–knit sense of community built between families who were in exile and acknowledges that many of them came back to South Africa with an education- something of which South Africans living in a country were systematically deprived. It’s an important addition to the multitude of stories of Apartheid-era South Africa, the transition into democracy and the birth of the so-called “born-free” generation.

Sisonke Msimang was born in exile in the 1970s. She is the daughter of South African resistance fighter Mavuso Walter Msimang, who had to leave his country ten years earlier. At the time, South Africa was still firmly in the grip of apartheid. Always Another Country is Sisonke Msimang’s autobiography, in which she portrays her life as strongly influenced by the attitude of political exiles and the frequent moves of her family to different continents. In an extremely self-critical narrative voice, Msimang recounts the contradictions she had to – and also wanted to – learn to live with.

The book is chronological, and the detailed descriptions of her childhood in Lusaka, Ottawa, and Nairobi, as well as her studies and first love in Saint Paul, Minnesota, serve to explain how she became the person she is as an adult. It took me a while to get into the book, but it is eye-opening to read to what extent the political elite in exile – as well as their children, who had never set foot in the country – identify with the idea of a free South Africa. Msimang becomes a cosmopolitan, experiencing moments as an outsider both in other African countries and in North America, but on the other hand she gains enriching perspectives. She becomes particularly passionate about Black American thinkers during her studies – from Malcom X to bell hooks and Audre Lorde.

Eventually, apartheid ends and in the 1990s Msimang’s family moves to South Africa. There, Msimang’s father becomes one of the first Black CEOs, and her mother also distinguishes herself in the returnee community, becoming “Entrepreneur of the Year” and “Woman of the Year.” Msimang always portrays herself as more radical than her parents because she is so absorbed in the theories of her studies. But she often fails in the question of how to live a radical life with a clear conscience.

Msimang observes the gaps that are opening up in the “new South Africa” – not only between Black and white, but also among Black people. She and her sisters speak perfect English but less well isiZulu or seSotho. For this reason alone, they are often perceived as arrogant. Thanks to their education and experiences abroad, all doors are open to them, which is far from being the case for all Black South Africans. Msimang is concerned about appropriate ways of dealing with her privileges. When she starts a job in the development sector, she meets Simon, a white Australian, and falls in love. This relationship adds even more to her critical self-questioning. I don’t want to give it all away here, but the book explores the question of whether the history of racism and apartheid makes such a relationship impossible.

The book is complex and shows how personal the political is. It is also in some ways a sad document of how hope in a free country soon turns into disillusionment. Msimang criticizes the new political leaders of South Africa: their egos are too big and they are too power hungry. Finally, she realizes that home is not bound to a place – South Africa – but depends on people. Today she lives in Australia, though her heart is still closely tied to South African politics. I look forward to reading Msimang’s second book soon, a biography of activist and politician Winnie Mandela.

Can you tell us about your early reading life? What stories were you drawn to as a child and what books left a lasting impact on you?

SISONKE MSIMANG: As a child I read everything in the house — both books and magazines. I loved National Geographic, I read Little Women and lots of books about horses. I was an indiscriminate reader when I was a kid and because I was rewarded with compliments whenever I had my nose in a book, I tried to read things I was sure not to understand simply because I knew it would impress everyone. Not a great strategy when you have no clue what any of it means!

You grew up as part of the South African diaspora living in many places on the African continent and North America. Can you speak about how this sense of home and this movement contributed to your desire to become a writer?

Because we moved around a lot, I was always looking for continuity and consistency. In some ways books provided that. We were an English-speaking household, and we lived in English-speaking countries in Africa and North America. So I could always check out library books or swap books with friends. So my first identity when it comes to books, was as a reader. Books were a sort of home for me. And so in some ways, the state of rootlessness that accompanied our many moves, combined with the relative safety of books made reading (and later writing) a familiar place for me. I only came to writing late in my life. I always wrote — especially in university — but I didn’t see it as a viable option, in terms of a career. As a middle class African woman whose parents had drummed into my head the idea that I had a responsibility to help rebuild South Africa after the end of apartheid, I really thought my role was in the professions — working towards making my country stronger. Writing just didn’t feature.

Tell us about Always Another Country. How did you come to write the book? What compelled you to speak about your life as part of broader historical changes in the world?

The good thing about getting older for me it that I have deepened my politics and begun to make connections that weren’t possible for me 20 years ago. So it was only in the last five years that I began to understand the way Nelson Mandela’s political choices had so profoundly framed the trajectory of my family. His radicalization and decision to form an armed wing of the African National Congress, triggered my father’s departure. His freedom signaled our ability to return to South Africa 30 years later. So my life is literally entwined with the recent history of South Africa. I am of course not alone in this regard and so it seemed like writing about my self would be a way of writing about politics but also of reflecting the experiences of many other South Africans whose stories have been overshadowed by the larger story of Mandela and his comrades.

One thing that many readers may notice is that there are layers and layers of stories here. It is a story about you, but it is also a portrait of a great many characters, from family to friends to lovers, and, all along the way it is a testament to the strength of women. Who are the other people in the book? Why them and what did you learn from writing about them?

Its really a story about my family — my mother plays a central role. But its also about people who were the casualties of apartheid — like Thandi Shezi whose testimony at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission really haunted me. She was raped and brutalized. It’s also the story of these remarkable aunties I grew up with — Aunty Angela and Gogo Lindi — who were independent and rejected convention and who taught me a lot about fearlessness without having to articulate it as a politics. These days there’s a lot of talk about how brave people are. The women in my stories didn’t talk about being brave — they simply lived their lives in the most courageous fashion. Writing about them was helpful because I had always assumed my feminism was the result of intellectual decisions I made in high school and at university. Looking back, it would have been hard for me not be to be a feminist given their influences on me.

How does this fit with other questions of identity, in particular a question having a double-consciousness of place that has always been political, of how you have moved in real and literary terms?

It’s interesting, I tried very hard not to write this book in didactic terms. I didn’t want to write about identity (though I did in places) I wanted to weave a sense of how the people I grew up with were these eccentric, funny, fully human characters — which unfortunately, is still seen as political. The fact that they are contemporary complex Africans not living in villages and traveling the world and continuing to be African — well that is who they are. And yet writing about this is cast as a political act. Which makes me sad, but also, is part of the on-going battle black people face everywhere — both in real and literary terms. So there’s a double bind there — you are writing about yourself as you are and you are for yourself and for your people, but you are also conscious of constructing a new narrative about who you and your people are for an audience that has low expectations. The latter is not a huge concern in my mind, but they become a big deal because of how loudly they read, in other words, how much power they have.

In thinking about Always Another Country in our world and times, can you speak to what this act of reflection means now? The era of Apartheid and the early days of a free South Africa seem very different, from one another, but also from the world now. You talk about this in your other book The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela. What do you make of the current global situation?

Honestly, I am at a loss. I have been trying and failing for some time to wrap my head around the current global moment. The politics are nasty, the sense of being under siege is strong. I am desperately trying to be optimistic but I am struggling to find solid intellectual bases for that optimism. The act of reflection — of slowing down — is precisely what we need at this stage. Too much happens too quickly — without the time for reflection. And yet the forces propelling this speed are powerful. I have kids, and the pace of rage, and the speed of anger; the ways in which we are wreaking damage of the environment more quickly than we ever have even as we are more aware of the effects of our actions — these things literally keep me awake at night, fearful for them. Writing about this must be part of resisting them, but I will be honest, it feels incredibly tough right now.

Building from this last question is the question of how writing matters now and what kind of work it is called upon to do. You are a board member of PEN South Africa, and continue to be active there despite now living in Australia. Talk to us about PEN, free speech, and the responsibilities we have as citizens and writers?

I’m also a member of PEN Australia and for me the PEN movement is a crucial part of a larger strategy to ensure that the speed and pace and nastiness does not crowd out the spaces for reflection. Writers need freedom in order to think. It really is that simple. Where state and private actors try to curtail the freedom of writers and artists to express themselves, where they try to hold back our ability to think and to share our words and ideas, we see the collapse of democracy, we see the collapse of protections of the environment, we see corruption. So I see it as my role as a citizen of South Africa, and as a member of Australian society to advocate for space and freedom — even for views I don’t like. Not for hate of course, but certainly for the glorious right to argue.

Finally, what is the next long piece of writing you are working on, and, how does it respond to a future that we are making as we go along?

Oh the hardest question of all! I am interested in small town murders. I am also interested in how much the language of the culture today is drawn from trauma studies — the rise of the use of the word “triggered” fascinates me, given how often it is used in non-trauma settings. So somewhere between those two interests, I am hoping to write something that makes meaning of where we are — at least for myself.

‘Few of us have felt the grinding force of history as consciously or as constantly as Sisonke Msimang. Her story is a timely insight into a life in which the gap between the great world and the private realm is vanishingly narrow and it bears hard lessons about how fragile our hopes and dreams can be.‘

Tim Winton

‘Brutally and uncompromisingly honest, Sisonke’s beautifully crafted storytelling enriches the already extraordinary pool of young African women writers of our time.’

Graça Machel, Minister for Education and Culture of Mozambique

‘A brave and intimate journey. Msimang delivers a deep call for fierce courage in the face of hypocrisy and compassion when faced with our shared humanity.’

Yewande Omotoso, author of The Woman Next Door

‘Sisonke Msimang kindles a new fire in our store of memoir, a fire that will warm and singe and sear for a long, long while.’

Njabulo S. Ndebele, author The Cry of Winnie Mandela

‘Msimang pours herself into these pages with a voice that is molten steel; her radiant warmth and humour sit alongside her fearlessness in naming and refusing injustice. Msimang is a masterful memoirist, a gifted writer, and she comes bearing a message that is as urgent and timely as it is eternal.’

Sarah Krasnostein

‘It is rare to hear from such a voice as Sisonke’s—powerful, accomplished, unabashed and brave. This is a gripping and important memoir that is also self-aware and funny, revealing the depths of a country we’ve mostly only seen through a colonial perspective.’

Alice Pung

‘It is not possible to do this book justice in so few words…Always Another Country is eloquent and powerful. Msimang’s explication of what it means to be from – but not of – a place is profoundly moving. Msimang deserves to be widely read and fans of Roxane Gay and Maxine Beneba Clarke, in particular, will not be disappointed.’

Readings

‘An excellent blend of both the personal and political…a bold memoir…a tale that will sustain itself for generations.’

Books & Publishing

‘[An] eloquent memoir of home, belonging and race politics.’

Big Issue

‘Msimang is a talented and passionate writer, one possessed of an acerbic intelligence…This memoir is also full of warmth and humour.’

Saturday Paper

‘Eloquently, intelligently and passionately written…A gift of gritty reality in a fake news world. [Sisonke’s] greatest strength is her willingness to examine concepts such as freedom, racism, gender relations, and the ability of peace and prosperity to exist under conditions of verbal and physical violence. It makes this book an inspiration for all those trying to make some sense of the world in which we find ourselves.’

Otago Daily Times

‘This eloquent, moving and heartfelt memoir will have readers riveted from start to end…Sisonke’s passion, idealism and courage beam true from every page.’

WritingWA

‘A graceful memoir.’

New York Times

‘Msimang’s graceful memoir is one of those rare books that managed to make me less cynical about the state of literature…It’s a coming-of-age story for those children for whom home is marked by more than a single physical location.’

New York Times

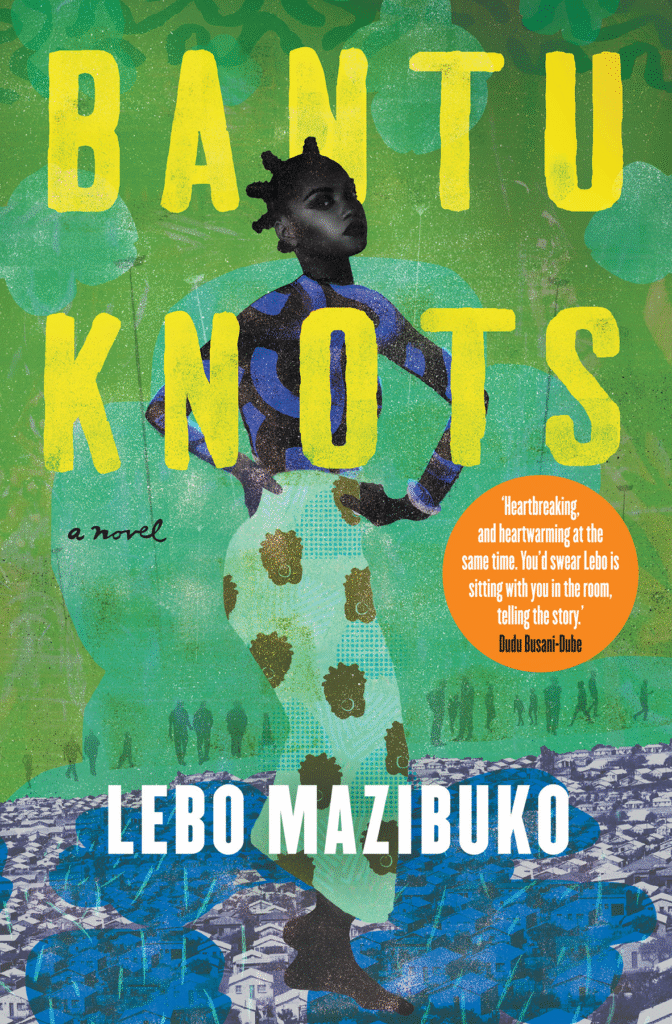

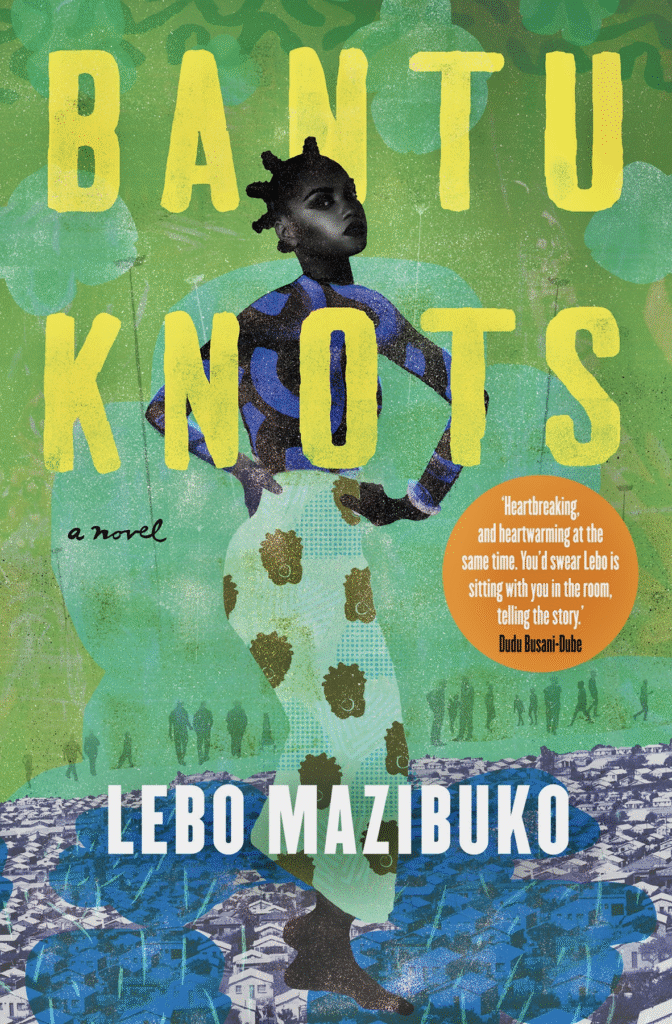

7) ‘BANTU KNOTS’ by LEBO MAZIBUKO (Published 2024)

BANTU KNOTS tells the story of a complex Mother-Daughter relationship, and a coming-of-age journey that seamlessly interrogates identity, culture, womanhood, and the push and pull of tradition and modernity. We follow young Naledi, the protagonist of the story as she forgives an absent father, grapples with the pressures of womanhood, and pursues her dreams regardless of her circumstance. A victorious debut, BANTU KNOTS raises meaningful questions and answers them.

In her debut novel Lebo Mazibuko ushers us into the world of Naledi, Dineo and Norah (Mama). These three people are tied by blood and present different personalities mirroring society and to some extent life in the township. Naledi the girl with the Bantu Knots, a signature hairstyle which she one day abandons for something more unusual either as a radical act of defiance or fresh start but the two are not mutually independent. Mazibuko tackles important themes in this novel such as; the family setup, friendship, body image, relationships, gender based violence, sexual violence, sex, religion, romance, womanhood, liberation and growth.

With each chapter adorned by beautiful proverbs in various South African languages such as Setswana and isiZulu, Bantu Knots by Lebo Mazibuko is a delightful coming-of-age story of a young black woman growing up in a township environment. At its core, this latest novel is a celebration of strong black women that many readers can identify with. Besides the emphasis on the typical “African woman” attributes of being curvaceous and brown-skinned beauty- the author crafted most female characters as bold, independent thinkers and deeply entrenched in their beliefs. Mazibuko stunningly weaved Kasi symbolism that would have many readers identifying their family members, neighbours and nyaope boys asking for two rands. This easy read explores complex themes around self-identity and beauty ideals, marriage, teenage pregnancy, gender-violence, youth unemployment and religion mostly embedded in a township setting.

Naledi Kwena

Rooted in her funny popcorn knotted hair the main character Naledi Kwena better known to her friends as Ledi, is a lover of jazz and poetry trying to find her voice in a chaotic world. Referred to as “Myamane” by her estranged father she sometimes finds herself an outcast due to her dark skin. At the beginning of this novel, we catch Naledi as a twelve-year-old teenager and follow her narrative into her twenties. We empathise; get angry; laugh and cry with her at every twist and plait of her life. From her first kiss; battle with understanding boys and sexuality; her questioning of the role of religion in a changing world and adapting to tertiary life.

Strong Black Women

Naledi’s mother Dineo, although an irresponsible parent addicted to slay-queening and the belly-popping-blesser lifestyle, is still feisty and can stand up for herself when it suits her. Mazibuko navigates us between this unpleasant mother-daughter relationship whereas a reader you wonder whether the relationship could be salvaged or not. The same can be said about the mother-daughter relationship between Mama Norah, Naledi’s grandmother, and Dineo. A matriarch of note with unshakable and uncompromising Christian values, Mama Norah is highly protective of Naledi mainly because she doesn’t want her to fall into the trap of teenage pregnancy and otherworldly sins. This prayer warrior, who wastes no time to remedy a devilish situation with a Bible verse or two, is a representative of many grandmothers across rural and township South Africa.

They are the custodians of love, wisdom, humility and faith with the best interest of their children and grandchildren tucked unconditionally in their hearts. These grandmothers know all about holding the knife’s edge without flinching. This mission however may come across as incredibly strict and unfair to those under their guardianship as was the case with Naledi. To this strictness, Naledi states “My grandmother’s voice had been thick and heavy, like the bags beneath her eyes. It had shaken everything- from the walls of our four-room house to every hair on my body”. Just like a hairband, Mama Norah is one of the woman characters that firmly hold together the essence of this book.

“Moriri oa mosali ke lesira”- A woman’s hair is her veil

As a teenager “Rasta” was the prestigious title, to the disdain of my parents. I earned from some Kasi residents due to my green-bar-Sunlight-twisted dreadlocks. At some point, there were street sage recommendations to use Coca Cola or Fanta Orange cold drink to get the shiniest and steadiest dreadlocks. Failing to follow through, there were also short-lived periods of S-curl and Cut, even cornrows. Now in my adult life, I find comfort in my chiskop, however, hair and beauty issues are not much of a comfortable topic to explore especially amongst African black women as compared to us men. One character that unapologetically tackles these issues is Itu, the new friend Naledi meets through the pastor’s daughter Minenhle, known as Minnie.

Itu is a firebrand of a personality that challenges societal constructs and the hypocrisy of patriarchy with her political-feminist views. To the long-held debate that black African women straighten their hair and make other body alterations due to low-esteem and self-hatred, Itu responds with unwavering might. She states “when Kourtney puts on hair extensions, fake lashes and gets a nose and boob job, Kourtney is so sexy, but when Khetiwe does it, she’s not proud to be an African woman”. With the plaited and twisted popcorn knots most of her life, for Naledi her hair has not been the main priority compared to other girls like Minnie. Echoing one of India Aria’s songs this book prompts one to question if we are really our hair. To this Itu argues “It’s not just hair…even though hair is one way we use to express ourselves. It’s our hair, our fashion, our language, history, culture and even our beliefs“.

A celebration of African township culture

Bantu Knots is also a celebration of township culture that I related to, having grown up in Mabopane, a township north of Pretoria. I was familiar with the imagery of the women characters wearing nightgowns during the day with pantyhose on their heads; counting money at the front seat of a taxi, and the infamous old orange sack used to wash dirty bathtubs.

These are the things we grew up with and it is still the current reality for many South Africans. For those readers who have climbed the social class ladder, this book will serve a nostalgic Kota feast you wouldn’t want to end. Although the author does a decent job of translating some vernacular words, not all parts in South African languages are translated. This prevailing tone of township dialect through the book could mainly appeal to black township audiences and thus risk sidelining other audiences interested in the book. Additionally on whether the overall theme of the politics of Bantu hair was fully explored is another thing the readers will have to conclude on.

Over and above that Bantu Knots is a worthy fictional contribution to this political issue particularly from an African Black hair perspective. This beautifully written novel is not only a story of a young woman finding her voice to stand by her decisions but also pays lovely tribute to all African black women who rise above adversaries, forgive and get reborn.

Johannesburg based, Rolland Simpi Motaung is an Entrepreneur, Facilitator and Book Reviewer. He is passionate about entrepreneurship, education, creative arts, media and gender studies particularly from an African context

8) ‘RECLAIMING THE SOIL’ by ROSIE MOTENE (Published 2018)

Justas Matiwa’s debut novel Coconut explores the Cultural Confusion and Identity crises, that result in Black children raised in a white world, so too does Motene’s book. In contrast, however, RECLAIMING THE SOIL: A Black Girl’s struggle to Find her African self is instead a non-fictional and biological account set during Apartheid South Africa. As a young Black girl, Motene is taken in by her Jewish family her mother works for. And why she is exposed to more opportunities than she would have had she chose to remain with her Black parents, hers is a Story of tremendous sacrifice and learning to rediscover herself in a world not meant for her.

The power in this story is Rosie’s acknowledgement of her part in it. The part where she wanted, with all her heart, to shed her black skin and all that which came with it. The poverty and the lack. The shame of her mother’s job. Her mother was a domestic for the Finkelsteins. And Rosie treated her with utter disdain. Rosie did everything in her power to fit in with the Finkelsteins. As an adult, Rosie wanted to go back to her people. The journey was a long and painful one but, she persevered. She hasn’t completed the journey yet but, she still soldiers on.

Rosie’s story is a reminder to society that when races are pitted against each other, it’s the children who suffer most. These children grow into lost and wounded adults if not healed. We end up with hurt adults wondering aimlessly through their lives because they don’t have a firm grounding in anything. There’s nothing concrete grounding them and they use substances as a salve on porous foundations.

Reclaiming The Soil is a powerful journey of a black woman brought up in whiteness, not just whiteness but Caucasity, to reclaiming her blackness against all odds.

9) ‘WE HAVE EVERYTHING WE NEED TO START AGAIN’ by KOLEKA PUTUMA (Published 2024)