For those of us in the Northern hemisphere, Summer tends to usher us ample time of relaxation focusing on other recreational activities that brightens our day. This season brings with it plenty of opportunities to lounge outside or by the pool with a book in hand. For an exciting summer read, we’ve compiled a list of novels and short story collections by African authors released within the last decade and forthcoming, that are sure to stimulate, surprise and entertain you in every sense.

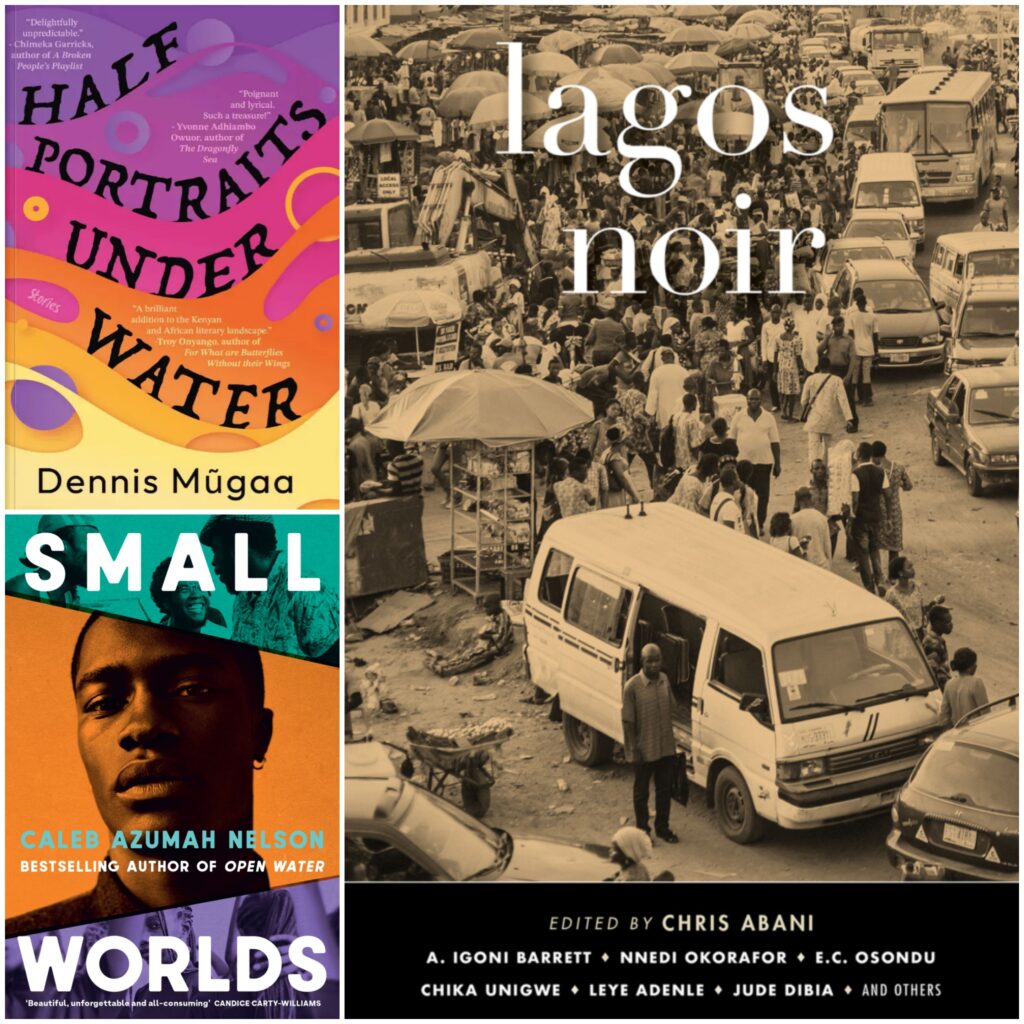

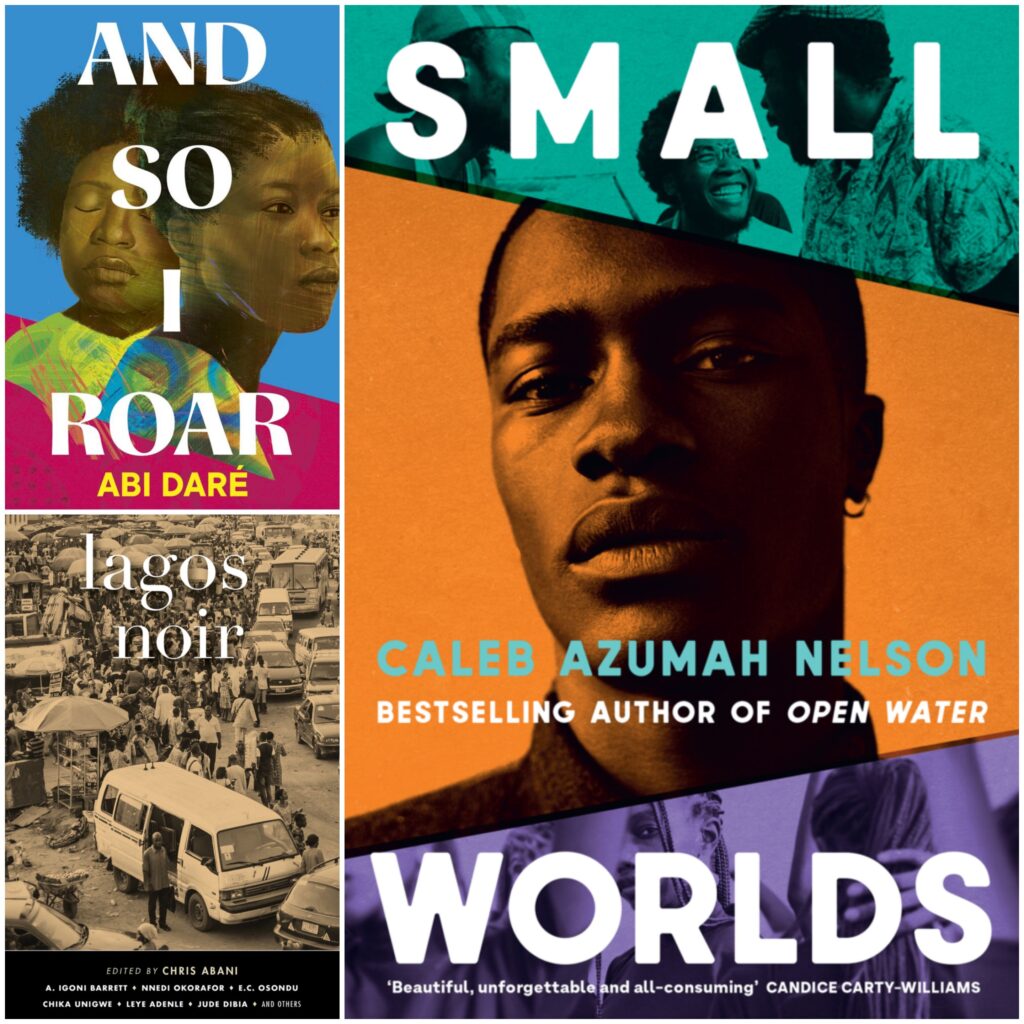

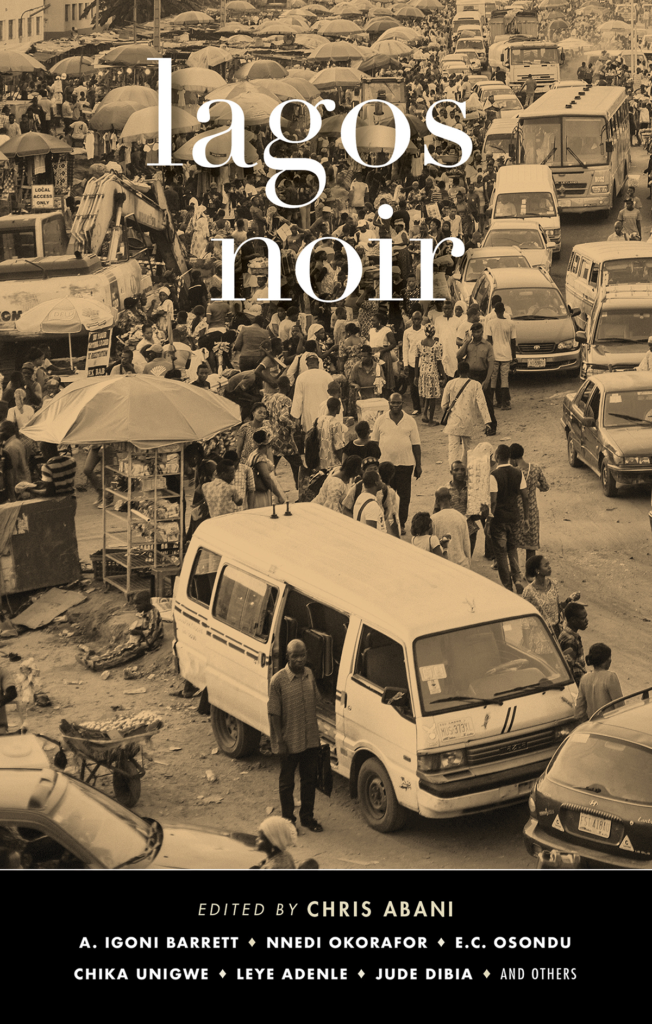

1) ‘LAGOS NOIR’ edited by CHRIS ABANI

Many stories have been written about the continent’s largest megabits, but let’s be honest you can never have enough stories about Lagos. Released in 2018, Lagos Noir is an anthology edited by acclaimed poet and novelist Chris Abani and features 13 stories by writers including E.C Osondu, Nnedi Okorafor, Jude Dibia, China Unigwe, A. Igoni Barrett, Sarah Ladipo Manyika, and Leye Adenle.

Here this beautiful lady talks about getting ‘disgustingly educated’ this 2025!! and listed the following books as her 2025 go-to Classic science fiction stories edited. by Adam Roberts, Lagos Noir edited. by Chris Abani, Face me I Face you by oyindamola, The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, The New York Stories by John O’Hara, Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, In The Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado, The Best American Short Stories edited. by John Updike.

Lagos Noir is the latest in the series of “Noir” books from Akashic Books that have been taking readers on a tour of the backstreets and hidden lives of cities around the world. Featuring stories collected by writers from the city featured, this collection is edited by Nigerian born novelist and poet Chris Abani.

While most readers will associate the designation “Noir” with detective stories featuring hard boiled investigators dealing with assorted villains and femme fatales while trying to solve some sort of nasty murder, it also can refer to any depiction of life that goes on in the shadows. Not necessarily criminal activity, but something unsavoury or unsettling. The collection of 13 stories Abani has put together bings Lagos, largest city and former capital of Nigeria and one of the largest cities in Africa, to life.

From seedy back allies to the houses of the wealthy, we are given a glimpse into a world few North American readers have ever experienced or quite probably, understand. This is a place where corruption among everyone, from police to the lowliest of landlords, is expected. Whether its motorcycle taxi drivers, (known as okada) having to pay a percentage of their takings to random police roadblocks or a person seeking to rent an apartment having to line the pockets of both real estate agents and landlords to even have a hope of finding a somewhat decent apartment.

However, that doesn’t stop people from dreaming of a better life. Yet as we see the obstacles placed in their way are pretty much insurmountable no matter what most of the characters we meet try. There’s the honest cop in the collection’s opening story, “What They Did That Night” by Jude Dibia, who finds not only his fellow cops don’t want him investigating a murder, but his wife aligned with the criminals as well in demanding he take their bribes and look away.

Then there’s the poor okada driver in “Heaven’s Gate” (Chika Unigwe) who just wants to make enough money to help his family back home and rent himself a nice apartment. However you can’t always prepare for the unexpected, and he discovers corrupt cops are just as dangerous as criminals.

The stories aren’t all dark. There’s some wonderful moments of humour as well. Nnedi Okorafor’s “Showlogo” is the story of the so-called indestructible small time criminal known as ‘Showlogo’. When thing get too hot in Lagos for him he stows away in the undercarriage of a plane bound for New York City.

Somehow he not only survives the journey but also the jumping out of the airplane onto a NYC suburb’s sidewalk. His audacity is only matched by his durability as he casually picks himself up off the sidewalk and strolls off to find out what’s what – much to the amazement of the two who witnessed his fall from the sky.

Each story in its turn peels back another layer of the mystery surrounding the city of Lagos. Perhaps not all of the stories are what we would call “Noir”, but they all help to create a sense of intrigue and danger about the city they have in common. Every city has its secrets and dirty linen – these stories give us a glimpse of that reality in Lagos.

Chris Abani has pulled together a wonderful collection of stories form many different voices. In some ways its like having 13 separate tour guides each of whom are dedicated to showing you a different aspect of their city. From roadblocks manned by bandits who demand money and ATM cards so they can steal your cash to even a take on the ‘you’ve been left money by a Nigerian’ scam which plays on European stereotypes of Africans and Nigerians beautifully.

This may not be the book the Nigerian tourist industry wants you to read as an inducement to come visit their country, but it sure is a lot of fun to read. Each of the writers brings their own little piece of Lagos to life with such vividness you can almost hear the rats stirring in the garbage and feel the layers of humidity and heat weighing on your skin.

Akashic Books continues its award-winning series of original noir anthologies, launched in 2004 with Brooklyn Noir. Each book comprises all new stories, each one set in a distinct neighborhood or location within the respective city. Now, West Africa enters the Noir Series arena, meticulously edited by one of Nigeria’s best-known authors.

Brand-new stories by Chris Abani, Nnedi Okorafor, E.C. Osondu, Jude Dibia, Chika Unigwe, A. Igoni Barrett, Sarah Ladipo Manyika, Adebola Rayo, Onyinye Ihezukwu, Uche Okonkwo, Wale Lawal, ‘Pemi Aguda, and Leye Adenle.

From the introduction by Chris Abani: Lagos has, like many coastal cities, a very checkered and noir past. It is the largest city in Nigeria and its former capital. It is also the largest megacity on the African continent, with a population approximating 21 million, and by itself is the fourth-largest economy in Africa…. It is rumored that there are more canals in Lagos than in Venice. Except in Lagos they are often unintentional. Gutters that have become waterways and lagoons fenced in by stilt homes or full of logs for a timber industry most of us don’t know exists. All of it skated by canoes as slick as any dragonfly. There are currently no moonlight or other gondola rides available….

The 13 stories that comprise this volume stretch the boundaries of “noir” fiction, but each one of them fully captures the essence of noir, the unsettled darkness that continues to lurk in the city’s streets, alleys, and waterways…. Together, these stories create an unchartered path through the centre of Lagos and out to its peripheries, revealing so much more truth at the heart of this tremendous city than any guidebook, TV show, film, or book you are likely to find.

“In the introduction to this excellent anthology, Abani welcomes readers to Lagos, Nigeria, a city of more than 21 million and an amazing amalgam of wealth, poverty, corruption, humor, bravery, and tragedy. Abani and a dozen other contributors tell stories that are both unique to Lagos and universal in their humanity…. This entry stands as one of the strongest recent additions to Akashic’s popular noir series.”

“Lagos, the largest city in Nigeria, with a population of 21 million, has, like many coastal cities, a ‘very checkered and noir past,’ writes novelist Chris Abani in his introduction to this anthology.” (BBC Culture)

“The beauty of this book, which contains 13 stories from Nigerian writers, is that it serves as a travelogue, too.” (Bloomberg, included in “The Darkest Summer Reading List for Those Bright, Beachy Days”)

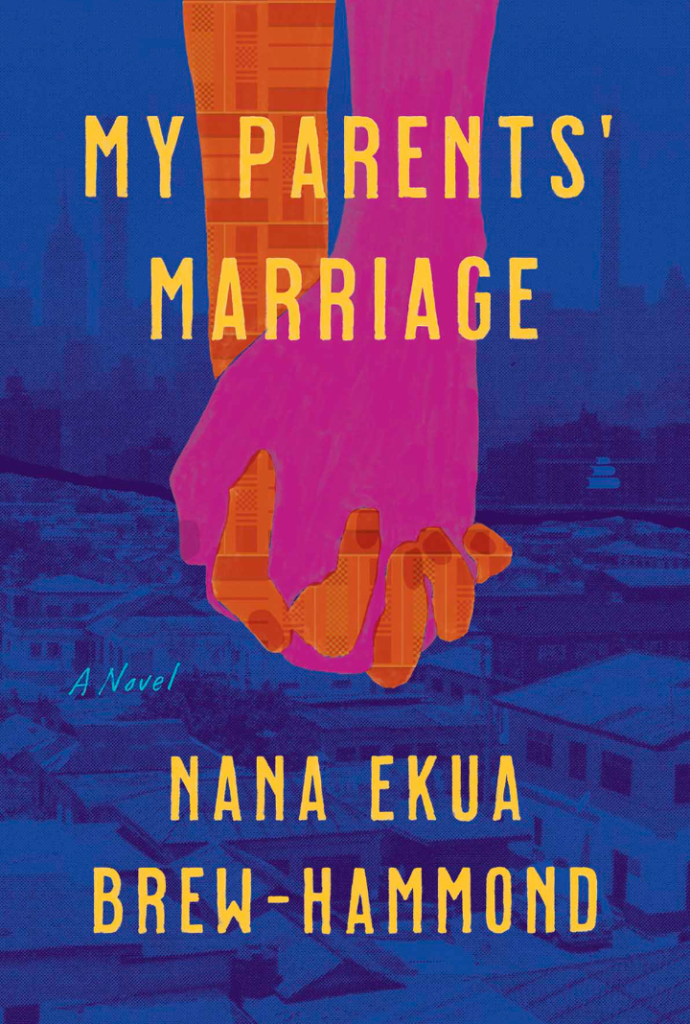

2) ‘MY PARENTS MARRIAGE’ by NANA EKUA BREW HAMMOND

Cultural identities, Intimate relationships, and Family complexities intertwine in Nana Ekua Brew Hammond’s sophomore novel, ‘My Parents’ Marriage. The novel tells about the story of love and understanding through three generations of a Ghanian family. Hammond, a Ghanian American writer, is known for Powder Necklace, and Blue: A History Of Colours as deep as the Sea and Wide as the Sky. Her works have appeared in the Village voice, Metro and elsewhere.

Acclaimed children’s author Nana Brew-Hammond makes her highly anticipated return with this soaring and profound story about love and understanding told through three generations of one Ghanian family.

Synopsis:

Determined to avoid the pain and instability of her parents’ turbulent, confusing marriage, Kokui marries a man far different from her loving, philandering, self-made father—and tries to be a different kind of wife from her mother.

But when Kokui and her husband leave Ghana to make a new life for themselves in America, she finds history repeating itself. Her marriage failing, she is called home to Ghana when her father dies.

Back in her childhood home, which feels both familiar and discomforting, she comes to realize that to exorcize the ghost of her parents’ marriage she must confront them, not only to enable her own healing, but for the sake of her daughter who is considering a marriage proposal of her own.

Tender and illuminating, warm and bittersweet My Parents’ Marriage is a compelling story of family, community, class, and self-identity from an author with deep empathy and a generous heart.

Acclaimed children’s author Nana Brew-Hammond makes her highly anticipated return with this soaring and profound story about love and understanding told through three generations of one Ghanian family.

Determined to avoid the pain and instability of her parents’ turbulent, confusing marriage, Kokui marries a man far different from her loving, philandering, self-made father—and tries to be a different kind of wife from her mother.

But when Kokui and her husband leave Ghana to make a new life for themselves in America, she finds history repeating itself. Her marriage failing, she is called home to Ghana when her father dies. Back in her childhood home, which feels both familiar and discomforting, she comes to realize that to exorcize the ghost of her parents’ marriage she must confront them, not only to enable her own healing, but for the sake of her daughter who is considering a marriage proposal of her own.

Tender and illuminating, warm and bittersweet My Parents’ Marriage is a compelling story of family, community, class, and self-identity from an author with deep empathy and a generous heart.

“You think harmony happens just because two things have come together? No. The two parties have to do what they can to prevent a collision! You have to be alert. You have to keep your hands on the wheel and steer,” she said. “My daughter, you all are just beginning. You have to teach each other how things have to be. You have to correct him and give him a chance to make the correction.” (page 248)

My Parents’ Marriage (MPM) by Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond is a remarkable debut novel. Known for her short stories, picture book, poetry, and young adult fiction, in MPM Brew-Hammond delves into a highly emotive story of 23-year-old Kokui’s desires to escape from a dysfunctional family and pursue freedom by writing her destiny. Set across Ghana, Togo and New York, Kokui’s story begins with a rebellious night out at the Ambassador Hotel for Kokui and her sister Nami. In one the trajectory of her life changes. She meets Boris, whose life plans propel Kokui to chase the freedom she has always yearned for. Brew-Hammond tackles pertinent themes such as family dysfunction, love, womanhood, the mother-daughter relationship, inheritance and the political upheaval of the 70s.

Kokui wants to flee her dysfunctional family, a father who is a big wig and cannot stop amassing women and children. Her desire to escape is inflamed by the arrival of another child, Kofi, younger than Nami (her youngest sister), whose mother curses them. Her father, Mawuli Nuga, navigates society and the political situation easily; he is affluent and can bribe his way into and out of spaces. A man of his stature wields great power, and we see him doing great things at times. At his weakest he is seen abusing and taking advantage of women, first his office receptionist and later Micheline’s housekeeper, Afi. This is exactly the type of man Kokui does not want to end up with: five wives and countless children, but he cannot get enough. “Mawuli Nuga was rich, handsome, and magnetic. Men with that trinity of power could do whatever they wanted to whomever. It was up to the women to leave. But still. As a daughter whose mother had left without fully leaving, Kokui felt the betrayal of, and in, her sex.” (page 6). I questioned if Kokui’s issue was with polygamy itself or the brazen way her father handled it.

In Boris and their future together, Kokui places a great expectation- freedom, fidelity and security. Everything that her parents’s marriage never was. From a simple night when their paths cross, two strangers become two lovers whose young love and marriage are tested by their desires and the waves of life. Life happens. “She had known it wasn’t just her admiration for him that had drawn her in. Boris, too, understood the devastation of abrupt, cataclysmic upheaval in childhood.” (page 60). It is in this love story that Brew-Hammond’s pen shines; Kokui and Boris could not be any more different than together. Kokui has high expectations and is chasing a different marriage. Yet, in running towards that, one could not help but wonder if she was placing a heavier load on Boris without doing the necessary work herself. For Boris, the greatest worry is their compatibility. In Ghana, the class question confronts them, and identity issues arise in the USA. I appreciate how, in this narrative, where there are young people at the centre and a relatively new marriage, they are not spared of the growing pains.

Kokui questions why her mother, Micheline, left her father, left them with him and never divorced him. Here lies an exploration of the mother-daughter relationship, which we have seen take several colours in texts by African women. She does not want her parents’ marriage for herself; they are a couple that does not live together and only see each other for a week in a year. Kokui questions her mother’s love for herself, and even when she declares that everything she has done in life is for Kokui and Nami, she questions what a mother’s love for her children truly means. The betrayal she feels towards her mother evolves into resentment, creating a gaping rift between the two. Two important things happen to Kokui: she marries Boris and has three opportunities to become a mother. In this situation, she is tested. Did she judge her mother harshly? What is a sacrifice too great? “So much of her confusion and resentment over her parents’ marriage was bound up in her mother.” (page 117).

Brew-Hammond adeptly weaves the reader into the web of this relationship; there were times I did not understand Micheline, and even in the end, I wondered if her staying married to Mawuli had been worth it. There were also times when I felt Kokui was unfair to her mother, and even her expectations in life needed a dose of reality. Luckily for her, there are other examples, such as Sammy and Freda, Linda and Mike, Tim and Daphne. But do they do more harm than good?

I went into this read with an open mind, and I loved the writing, especially in the second half. There are other characters who, despite being minor, hold their fort: Nami, Freda, and Aunty Hemma. I am intrigued by Aunty Hemma. I want to know more about her and why she is the woman she is in this book. I would read an Aunty Hemma story any day. At one point, Kokui asks why everything about womanhood is distasteful, and whew! MPM is a gripping read!!.

3) ‘HALF POTRAITS UNDER WATER’ by DENNIS MUGAGA

On December 8th, 2023, Dennis Mugaga did revealed the cover for this amazing short story collection on X. ‘Half Potraits Under Water’ is a debut collection of ten loosely interlinked short stories about love and the interconnected nature of human experiences. Mugaga, a Kenyan Writer, has won the 2022 Black Warrior Review Fiction Contest, was shortlisted for Isele Magazine’s Inaugural Short Story Prize, and longlisted for the 2021 Afritondo Prize. His works often explores the theme of “Human Connection”. He is also a 2021/2022 Miles Morland Scholarship Recipients.

Half Portraits Under Water is a collection of ten loosely interlinked stories that explore love, loss, and the interconnected nature of human experiences.

Half Portraits Under Water is a collection of ten loosely interlinked stories that explore love, loss, and the interconnected nature of human experiences. In Kenya, a politician is murdered in broad daylight and several testimonies narrated to an unseen commissioner tries to get to the truth; a mother desperately tries to protect her freedom-fighting son from a ruthless and vindictive government regime; a young boy in a slum heads to a football pitch with his friend for what would be the last time as his country shifts politically to a new power; in an elite school for gifted young adults, a girl with a despotic father disappears and soon her three friends have to make a deal with the devil in order to hold on to their dreams. Through these stories set against the moving backdrop of sociopolitical changes in different countries, discover the profound connections that shape our lives, intertwining themes of love, grief, and what it means to be deeply, unflinchingly human.

4) ‘SOMEONE LIKE US’ by DINAW MENGESTU

Ethiopian American writer Dinaw Mengestu’s works explores themes of immigration, identity and African diaspora. ‘Someone Like Us’ follows Mamush, the son of Ethiopian immigrants, on a quest to uncover a hidden family story. Mengestu has received several awards and honors for his writing,including being named One of the New-Yorker’s 20 Under 40 Fiction Writers.

The doors are shut and the vehicle is in motion: readers participate in the journey undertaken by characters in Dinaw Mengestu’s fourth novel through the perspective of Mamush. When Someone Like Us opens, this young man—born in Ethiopia, raised in the suburbs surrounding Washington D.C., and now living with Hannah and their two-year-old son in Paris—is returning home to confront the gap between memory and history, to consider where he belongs.

At the heart of Mengestu’s fiction is the figure who has traveled some distance, worked hard to reestablish themself in unfamiliar places, and redefined their understanding of kinship. In his 2007 debut, The Beautiful Things that Heaven Bears, Stephanos comes to America with dreams of owning a deli but begins as a valet. In How to Read the Air (2010), Jonas struggles to reconcile his personal past with his work with refugees. And the core of 2014’s All Our Names is the silence where Isaac’s story resides, where he inhabits memories rather than share them with his social worker, Helen.

These characters have routines but not security, ties but not connections, and relationships but not commitments: Mamush, too, feels restless and rootless as he moves through space and time. His present-day reality is absorbed by his travels: in concrete terms, towards a suburb in Virginia; in psychological terms, through a past characterized by unanswered (often even unspoken) questions.

Readers’ security resides in total immersion in Mamush’s perspective and in Mengestu’s plain-speech recounting of events and his clear-eyed view: crucial when navigating uncharted territory between imagination and knowledge, truth and facts, isolation and connection. Mamush once created an entire backstory for the name applied to the fake I.D. card he later tucked between the pages of a book. He’s concerned with how people fully inhabit their lives—their day-to-day and the expanse of their being—and he’s become uneasy in his own skin.

There is an element of suspense in Someone Like Us, a slow reveal of what’s known and what cannot be known. While preserving those specifics unspoiled, one could say it’s akin to Jonas’s process in an earlier novel, where he expands the stories of refugees to satisfy bureaucratic requirements, expands the stories of strangers on the street even, as a means of expanding his understanding of history: if he “could imagine where they had come from and how they had gotten here,” then he could “add their stories to [his] own basket of origins.”

Also significant is the relationship between the truth of the experiences of key adults in Mamush’s life—initially his mother and Samuel and, later, Elsa, after Samuel marries her—and what facts remain as evidence (in court documents, for instance). Photographs are interspersed with narrative, images which draw attention to what’s beyond the frame of the image, to what readers and other observers cannot see or know, but what’s significant for characters in the novel. The text elucidates the characters’ truths, and readers recognize the invisible elements, the importance of what’s left unsaid and unaddressed.

Above all, matters of isolation and connection proliferate in the story. With Hannah, Mamush has a unique and intimate understanding. “We had built a dictionary of gestures and symbols that we trusted more than any phrase precisely because multiple meanings were always possible.” Silence, here, is not isolating: the absence of language is an opportunity for clarity. And opportunities to congregate might not always be joyful. Mamush is told: “If you want to be a writer… come to more funerals. It’s beautiful what we can make up.”

Thematically, this is where the bulk of the novel’s emotional power resides. As with writers like R.O. Kwon, Edward P. Jones, Amor Towles, Elizabeth Strout, Randall Kenan, and Bryan Washington, Mengestu is building a fictional universe, where characters who are central characters in one story appear on the margins of another story. Samuel, for instance, “often joked that if he didn’t find a new job, he was going to gather all his friends to form an Olympic team of parking garage attendants.” Readers familiar with Mengestu’s backlist will recognize Stephanos immediately. “We are world-class parkers,” Samuel declares, “We will take gold every time.”

Someone Like Us opens with a description of suburban Maryland apartment complexes, arranged as if “someone had drawn circles on a map and said these people will live here, and these here, and never shall they meet.” But the novel closes with one man’s story that traces the travels of these circles’ inhabitants. A single finger can trace the route between these seemingly isolated circles and remind readers that we can choose to meet. That if we can imagine it, we can make it true.

Dinaw Mengestu’s haunting novel about 21st-century American life starts with a sudden death. The deceased man is Samuel – a charismatic, witty, enigmatic Ethiopian immigrant whom our narrator, Mamush, thinks of as his father. But Samuel’s life will turn out to be every bit as mysterious as his demise, and as full of contradictions as America itself.

When Mamush learns of Samuel’s death, he leaves his wife and child behind in France and returns to the close-knit Ethiopian community in Washington DC that shaped his childhood. He’s propelled forward by feelings of personal grief, but also a professional urge to investigate the truth. Mamush is a journalist who, not unlike his creator – the recipient of the Guardian first book award for his fiction, and also accolades for reportage – has had success writing about conflicts at home and abroad. But he has grown tired of covering “long-simmering border conflicts and the refugee crises that grew out of them”, and meeting the needs of editors for whom, he drily notes, “dictators were once again all the rage”.

Samuel’s death gives Mamush a reason to undertake a journey across America – but how self-serving might that be? As his inquiries into the end of his father’s life unfurl, the question of what really happened to Samuel becomes something with more immediate, evolving stakes: what has really happened to Mamush? In chasing his father’s ghost, is he hoping to exorcise demons of his own? Hints of past addictions haunt his present sobriety. And his marriage to a photographer, who “takes pictures of apartment buildings on the verge of collapse”, feels like its own half-ruined structure awaiting demolition. His unappeasable mother gets one of the novel’s best lines when she questions how well her son’s expensive western education has served his overall happiness: “How can I get my money back. This is America. Refund.”

Someone Like Us starts out like a mystery novel but becomes something more like a ghost story

But reimbursements aren’t offered on the American dream. Before his body was found in suspicious circumstances, Samuel had been working as a taxi driver. He had harboured grand plans to expand his business: hiring drivers in Chicago, Ohio, Kentucky, he tells Mamush, will enable him “to get across the country”.

But a man who drives for a living also “knows better than anyone when someone is in the wrong place”. Samuel’s ambitions in America were never realised, and thoughts of his past life in Ethiopia left him feeling stuck in a state of not-quite-belonging – an inbetweenness that is beautifully baked into the very structure of Mengestu’s novel. The book’s main narrative journey is tightly stretched across three days. But that is just a frame for its constant, restless movement between past and present. Samuel’s life, chapter by chapter, rises up through the cracks caused by his death. Flashbacks continually resurrect and revise him until his enigmatic existence can be glimpsed from all angles.

“If this were a crime novel,” our narrator wryly admits midway through, “this would be the moment when Samuel confessed to having done something terrible.” But instead of blockbuster revelations, we get meandering Sebaldian reflections on selfhood, and ghostly photographs of buildings and faces inserted intermittently into the text. All of this increases the book’s exquisite sense of alienation. Like Teju Cole’s Open City or Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland, Someone Like Us is perfectly attuned to what it means to roam freely as an immigrant in America – a country that contains shards of all the other places its occupants have called home. A feeling of exile permeates Mengestu’s book to such an extent that the title comes to feel like its own quiet challenge: who do you picture when you read the words Someone Like Us? Is it a person of the same skin colour, class background, age? Or can our idea of the US – or any western country – be big enough to offer a more inclusive answer?

Someone Like Us starts out like a mystery novel but becomes, in the end, something more like a ghost story: a meditation on the ways we can be part of a place yet simultaneously separate from it. It is the kind of book Mamush’s father says he plans to write one day: a paean to the beauty and hardship present in his native Ethiopia, but also alive and present in every corner of the United States. “When I am finished,” he tells Mamush, “no one will believe a country can be so rich and so poor at the same time.”

5) ‘AND SO I ROAR’ by ABI DARE

Abi Dare first entered the literary scene with her Bath Winning novel, The Girl with the Louding Voice, a compelling account of an ambitious and resilient young Nigerian girl. Five Years Later, she returns with ‘And So I Roar’, a novel exploring themes of family secrets, identity and self-discovery. The story follows Tia, a young woman who overhears a conversation between her mother and her aunt that reveals a long hidden family secret. This discovery sets Tia on a journey to uncover the truth About her family’s past and her own identity.

Anyone who loved “The Girl with the Louding Voice” was hoping for a sequel, right? And here it is, “And So I Roar”. Warning: this does put one through the wringer rather – but justifiably so, I think.

Please listen, Ms Tia – so that you can count how many lucky you have in this life. Know this, your lucky is not because you are better than any one of us or because you have more intelligence, but because life make a choice for you to be born in another place at another time. So, to not listen to our stories is to believe that you are better than us. She’s right. But also wrong. We, the city-born and raised Nigerian women from middleclass and wealthy families, might be free of some harmful traditions and customs, but we still get the short end of the stick.

The essence that grounds “And So I Roar“ is rooted in Adunni’s resilience. Being resilient is remarkable, yet damning when it overextends to undue hardship or injustice. Abi Dare invites us again into Adunni’s world, a girl who remains an irrepressible force in the face of tradition and adversity. She is now fourteen and excited to begin school in Lagos. However, her journey is disrupted when a call from her village, Ikati, pulls her back to confront her past, sparking a pivotal conflict in the story.

This conflict sears the fabric of the plot and leaves gaping destruction in its wake. What is meant to create a rift between Adunni and her guardian, Tia, becomes a tightening bond. Their relationship beautifully mirrors the fierce protectiveness seen in Amaka’s relationships with her girls in Easy Motion Tourist. Tia isn’t just a guardian; she’s a haven for Adunni, much like Amaka is for her girls. Their connection is grounded in love, with Tia’s wisdom guiding Adunni as she bravely navigates the challenges of her past while easing her into a future filled with possibilities.

This highlights what being genuinely invested in someone means. It’s a heartwarming reminder that when women come together, they can uplift and empower one another to find and assert their voices. Tia’s journey of self-discovery runs parallel to Adunni’s struggle for independence, creating a rich dynamic where both characters learn from and lean on each other. The fierce love and protectiveness Tia shows are not just about saving Adunni but about challenging the societal norms that constrain women’s freedom and futures—and, perhaps, about saving herself, too.

The return to Ikati village is a symbolic journey for Adunni. More than just a setting, Ikati represents the weight of tradition, a place where girls’ futures are often decided by others, not themselves. Adunni’s return to Ikati feels like a confrontation with the ghosts of her past, and her fight for freedom is not just personal—it becomes a battle for the liberation of the girls in her community. Ikati is both a reminder of what Adunni seeks to escape and the ground where her ultimate test of strength and courage plays out.

Adunni’s resilience is central to her character’s journey in the story but reflects a nuanced journey. Her life is marked by hardship, yet she remains determined to find her voice and claim a future beyond society’s limitations. Throughout the story, Adunni demonstrates resilience not just by enduring her struggles but by seeking ways to overcome them and grow. Adunni’s resilience is not passive endurance; it’s about actively pursuing change through education, standing up for herself, or advocating for others like her. Abi Dare doesn’t romanticise her resilience as something she should aspire to at all costs. Instead, she portrays it as a necessity born from an unjust system. Adunni is resilient because she must be to survive and thrive in a world that frequently denies her autonomy and opportunities.

Abi Dare’s storytelling is ensconced in themes of empowerment and transformation, and in “And So I Roar,” this is made manifest in the clash between tradition and change. As Adunni and Tia confront the forces that threaten to silence young women, the novel spotlights the radical change that could happen through solidarity and the courage to claim one’s voice. Zenab, a remarkably bright young girl, fiercely displays this courage. From the onset, she ensures her voice is heard loud and clear regardless of the restraints on her freedom. She fights, sometimes physically, for justice and her beliefs. Spending time with her and knowing her reminds Adunni that her roaring voice should be heard even beyond her reach.

Abi Dare masterfully combines these themes with the vibrant cultural backdrop of Ikati, making it a force in its own right. The descriptions of the villages and the human activities punctuating the day are filled with masterful intent to explore the soul of Ikati. We’re shown how beautiful the land is and how the beauty is fast fading due to illegal deforestation. Abi Dare takes on different themes in this narrative, but the most sensitive one is showing women that they are not the blight that society makes them to be. This sequel reminds readers of the importance of stories and, more importantly, of the voices that rise from places like Ikati to demand change and assert their right to be heard.

This novel opens directly after Tia has rescued Adunni from modern slavery as a maid. Adunni’s got a place at school and all seems amazing and bright, then two envoys arrive from her village insisting she returns to take part in a ritual to a) help protect the village from the effects of climate change, and b) prove her innocence or otherwise regarding the death of her pregnant friend. Tia goes with her and the narrative alternates between their two voices, Adunni in her usual charming dialect, Tia in a much more Westernised and educated voice: these comparisons also allow Daré to make comparisons between their reactions to being in the village and rural conditions and making sense of their environment. She’s very clever: although we encounter various horrors such as child marriage, FGM, rape, child rape, murder and unpleasant ritual, not every Yoruba rural tradition is thrown out as outdated and horrible: mothers and daughters are close, everyone looks out for children and the community is everything, and we contrast that with Tia’s rather cold life back in the city. Tia also has issues with her family and husband, and has been put through a horrific fertility ritual by her wealthy mother-in-law, so no one is spared the horror.

The two voices are supplemented by others, for example the almost completely Westernised Zenab, asking for an iPhone and WiFi or the elderly woman who narrates Adunni’s family story. Once in the village, the girls who have been put together to perform the ritual tell their stories to each other: Tia is warned at one point not to look away from the horror of their stories, a reminder not to hide behind one’s White privilege either and look away.

I will say the story is quite slow at the beginning, and I wasn’t as interested in Tia’s story as in Adunni’s, even though Tia was meant to be more relatable to the Western / Westernised reader, I think. A decent follow-up though nothing will ever have the impact of the first book, and it raises interesting questions about women’s role in modern and traditional Nigeria and female education. I’m glad I read it, even though I had to steel myself at times.

Thank you to Hodder & Stoughton for approving my request to read this book. “And So I Roar” was published on 08 August 2024.

This probably isn’t a proper Bookish Beck Serendipity Moment as there were some books in between, but it was noticeable that this novel mentions the harsher effect of climate change induced by the Global North on the Global South, with African countries as the example, here in Nigeria, as “A Bigger Picture” did regarding Uganda and other African countries including Nigeria. Also, illegal logging plays a role in the plot and the environment, as it did in “The Friend Zone Experiment” which I read directly before this one.

Abi Dare is the author of The Girl with the Louding Voice, which was a New York Times bestseller, a #ReadWithJenna Today Show book club pick, a BBC Radio 4 Bookclub Pick,and an Indie Next Pick. Translated into 20 languages (till date) and studied on curriculums across the world, the Girl With The Louding Voice tells the story of Adunni, a 14 year old girl who is desperate for an education. The novel has received critical acclaim and has been shortlisted for several awards including The British Book Awards Best Book of The Year , The Nigeria Prize for Literature (Africa’s largest literary Prize), and in 2020 was named as the legendary Dolly Parton’s favourite of 2020 as well as selected as an Amazon Best Book of The Year for July 2020.

Abi grew up in Lagos, Nigeria and went on to study law at the University of Wolverhampton. She graduated as Best Performing Student in her MSc in International Project Management from Glasgow Caledonian University, and acquired an MA (with distinction) in Creative Writing from Birkbeck, University of London. A well-sought after speaker and teacher , Abi is passionate about storytelling and recently delivered a storytelling masterclass at Harvard Business School. In 2022, Abi was appointed as Board Member for the BIC Corporate Foundation. Abi lives in Essex, UK with her family.

6) ‘SMALL WORLDS’ by CALEB AZUMAH NELSON

Small Worlds focuses on love, identity, and belonging through the life of a young Black man in London. The novel portrays his relationships, personal struggles and search for a sense of home in a diverse city. Acclaimed for his lyrical prose and poignance, it builds on the acclaimed style of Azuma Nelson’s Debut novel, Open Water. In May 2024, Nelson was awarded the Prestigious Dylan Thomas Prize for Small Worlds.

An exhilarating and expansive new novel about fathers and sons, faith and friendship from National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree and Costa First Novel Award winning author Caleb Azumah Nelson

Peckham, a district of south-east London formerly associated with substandard housing, tabloid reports of criminality and overpolicing, has been in the throes of a remarkable transformation over the last decade. Not only has it witnessed gentrification but, as seen in the recent film Rye Lane and in Caleb Azumah Nelson’s novel Small Worlds, it is increasingly a site of inspiration for creative artists.

Small Worlds, the follow-up to Nelson’s multi-award-winning debut Open Water, focuses on Stephen, a teenage second-generation migrant of Ghanaian parents, Eric and Joy. Theirs is an involved and loving family. Stephen’s closeness to his mother is especially apparent in their tender biweekly visits to the Peckhamplex cinema.

The family’s small world is populated by a host of characterful Ghanaians, including the entrepreneurial Uncle T, whose “mouth [is] full of gold like its own sunshine”, and the shopkeeper/cafe owner Auntie Yaa, whose stock of yam, plantain and Supermalt brings a little bit of back-home to Peckham. Yaa’s also a quick-thinking peacekeeper. When youths chase after a local boy who runs into her shop, Yaa distracts the would-be assailants with homilies and questions about their parents.

Favorite Quotes

I don’t know what it means to move from one place to another, to make a home for yourself; to try and build a life from uncertainty. To have to do this alone, away from the people you love. I don’t know how this feels, so sometimes, like today, I ask

With every year that passes, the bond between my parents and Ghana begins to weaken. When they go back, they are treated like foreigners who have suddenly realized their heritage and are making a big return. They are expected to care for everyone, in monetary form or in gifts. To go back home is to wrangle with who you are against who everyone thinks you should be. It must be a strange feeling that this place my parents have longed for, a place they used to call home, could also reject them in their current form, could ask them to be someone else.

…grief makes language useless, and that only sounds might suffice

I pray then, like I’ve never prayed before, asking not for money, or a job, but that this new world I’m walking out into, this new world I’m building for myself, I ask that it be constructed from peace.

Sound helps us get closer to what we feel. Besides, language always has to be so exact and I never know exactly how I feel

Small Worlds is determinedly not another rehearsal of the kind of voyeuristic tabloid interest in Black people’s lives marked by violence and social deprivation; rather, it’s a love story. At least it sets out that way.

Some novels announce their intention from the first page. Here the burgeoning romance between Stephen and his fellow sixth former, Del, moves glacially from a beginning that risks appearing banal to an affecting meditation on the migrant experience.

Though a perceptive narrator, Stephen is frustrated by his own inarticulacy. Del is sassy and beautiful. “I want to say this to her,” he admits, “but outside of song and film, I’ve never heard this spoken.” It might help Stephen if he was more familiar with his parents’ mother tongue, but he informs us: “Mum always says my Ga has come home in a suitcase, like I’m a visitor in my own language.”

The novel would also benefit from a more generous inclusion of the rich hybrid of London/Ghanaian vernacular. One of the challenges Nelson wrestles with is how to make soap opera-ish everyday dialogue support the narrator’s intimation of the characters’ sophisticated interior lives. Their language may falter, but music and the capacity to dance liberate both Stephen’s peers and his parents’ generation from the daily oppression of Peckham life. In a two-step, swaying in the pews at church, Eric, Joy and other elders can trade sorrow and shame; and youths achieve much the same at the local dancehall.

The narrator returns to this motif repeatedly, but though Stephen is a jazz-loving trumpeter, his description of music’s power of transcendence is often overwrought – perhaps on purpose, to reflect Stephen’s earnest youth: “I play until I am spent, until the lines dividing who I am and the sound I’m making blur and thin.”

To deepen the portrayal of his characters, Nelson relies mostly on reportage. Del has been shaped by being an orphan. “Her life is informed by loss but because she’s lost, she loves freely, openly, with all she can.” We’re told that music is key to understanding Del’s character, but the author offers little to fire our imagination that how she plays the double bass, for example, might be a manifestation of her grief.

The novel works best when we’re given hints – to suggest, for instance, that the dark side of an otherwise happy family, the tension between father and son, has arisen from a glimpsed moment of intimacy between Eric and another woman which may have been misinterpreted by Stephen.

Other pivotal scenes, such as Stephen’s trip to Elmina Castle in Ghana, from where enslaved Africans were shipped to the Americas, are bolted on, and read like a shortcut towards unearned gravitas. In a novel told in three sections, not only is there a mystifying shift in register from a gentle love story in part one to the opening of part two, with the killing of Mark Duggan and the riots of 2011, but the narrator’s reflections on the ensuing conflagrations, though sincere – “We’re watching a group of people who are tired of being erased” – are unconvincing.

Intergenerational trauma is characterised by the estrangement of fathers and sons, stemming from paternal disappointment and rejection, following the sacrifices that come with migration. Towards the conclusion it becomes a governing theme, and although it works well as a coda it would have been more impactful had it been signposted earlier.

There’s a confident thrum of poetic prose in much of the writing, especially in the depiction of the reconciliatory tenderness between Stephen and his father. Overall, though, Small Worlds feels hurried. It’s only two years on from the much admired debut of this talented writer; Nelson would have been better served had the fruit of his writing not been plucked and forced to ripen before it’s ready.

Praise for Small Worlds:

Winner of the Dylan Thomas Prize

Shortlisted for the Orwell Prize for Political Fiction

Shortlisted for the Pattis Family Foundation Creative Arts Book Award

Longlisted for the Jhalak Prize

A Most Anticipated Book of the Year for The Millions, i-D Magazine, Esquire (UK), TheGuardian, Huffington Post (UK), BellaNaija and Literary Hub

A Best Book of Summer from Elle, Time, Times (UK), Marie Claire, Literary Hub, the New York Times, the Boston Globe, the Minneapolis Star Tribune, and the New Statesman

A Publishers Weekly Best Book of 2023

“Masterful.”—Minneapolis Star Tribune

“Small Worlds also shows how language, particularly narrative, can repair relationships or mend bridges between people . . . The point of language in moments like these . . . [is] simply to make a thoughtful offering in the hope that it meets with understanding, and maybe to build community. This, I believe, is the most important work that Nelson is doing with his words, and I look forward to seeing what he does with them next.”—Brooklyn Rail

“An ode to the West African immigrant community in London, a coming-of-age tale of young love and yearning, and a quietly powerful meditation on intergenerational conflict and trauma… Small Worlds is an achingly tender, exquisitely rendered portrait of a truly beautiful soul.”—Literary Hub

“There’s something wide-eyed and lovely about the way Caleb Aumah Nelson writes about what it is to be young and alive to the world… This novel is about the dynamic between a father and son over three summers in London and Ghana, but it is also about music, and dancing, and those pleasures in life that are simple and yet also everything.”—Esquire, Most Anticipated Books of 2023

“Finely drawn and lyrical.”—GQ

“Observed with candour and flowing clarity.”—Financial Times

“Deeply intimate and poetic.”—Marie Claire (UK)

“Emotionally astute… not only touching but well formed.”—New Statesman (UK)

“Small Worlds resonates and reverberates with the true language of our souls. Drop the needle on it.”—Irish Times

“Both intimate and international, anchored by a timeless story of friendship and growing up.”—The Millions

“Written in exquisite prose infused with lyricism, the book examines the unexpected repercussions of life decisions and explores such themes as faith, friendship, and authenticity.”—Christian Science Monitor

“A beautifully rich novel celebrating love and art and conducting an in-depth exploration of the joys and pains of Black youth.”—Booklist

“Astonishing… Nelson’s assured writing captures the pulse of a dance party, the heat of a family’s bond, and the depth of spiritual fervor to conjure a story as infectious as a new favorite song.”—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“The musicality of Nelson’s language underscores this vibrant and deeply moving tale of love, family, and coming of age. While stories of conflict between first-and second-generation immigrants are common, the cultural richness and specificity of Nelson’s narrative rises above tropes and stereotypes.”—Library Journal, starred review

“Azumah Nelson’s characters are intelligent, and his poetic, elastic, bright prose has an uplifting energy, even when he’s writing about the pain of loneliness… Azumah Nelson is something new: an unashamedly clever, spiritual, angry, loving voice in fiction, just when we need it most. Small Worlds is a book for everyone… No one could fail to feel the message, of always striving for emotional honesty and hope, that is at the heart of this uplifting symphony of a summer read.”—Times (UK)

“An affecting meditation on the migrant experience.”—Guardian (UK)

“Nelson is a rhythmic writer, using repeated motifs—variations on phrases about what we remember and what we forget, about dancing to solve problems, about the way the sun catches the back of a loved one’s neck—to make this touching novel perfectly formed too.”—New Statesman (UK)

“Rare life ripples through this hymn to a city’s rhythms.”—Daily Mail (UK)

“What makes Azumah Nelson so seductive is the way he nails how it feels to be young, in love, in London in the summer, with possibility stretching out ahead. His territory is the after-hours funk clubs of Deptford and Peckham frequented by black people in search of music and kinship; the Caribbean cafés that stay open into the small hours; the journeys back home on the night bus. Thanks to his supple, lambent prose, it’s a landscape that dazzles.”—Telegraph (UK)

“Small Worlds is a miracle of observation, of attention and attunement. Caleb Azumah Nelson writes prose that is unmatched in its musicality and sensitivity. A gorgeous, rhapsodic, wise novel.”—Katie Kitamura, author of Intimacies

“The rhythms of Small Worlds are a feature of Nelson’s quiet, particular ear and of a profound engagement with music. Nelson writes about closeness, with family, with lovers, with art, as careful, essential labour.”—Raven Leilani, New York Times bestselling author of Luster

“A novel that feels as intimate as it does expansive; Caleb Azumah Nelson has given to us a love story that goes beyond two people. Instead, there are no bounds to his exploration of exactly what the heart can feel. Beautiful, unforgettable and all-consuming.”—Candice Carty-Williams, Sunday Times bestselling author of Queenie

“In his beautiful new novel Nelson summons the sounds of Black Youth, love and discovery to the page. A celebration of the heart.”—Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, author of Friday Black

“Touching, heartfelt, and musically rich.”—Diana Evans, author of Ordinary People

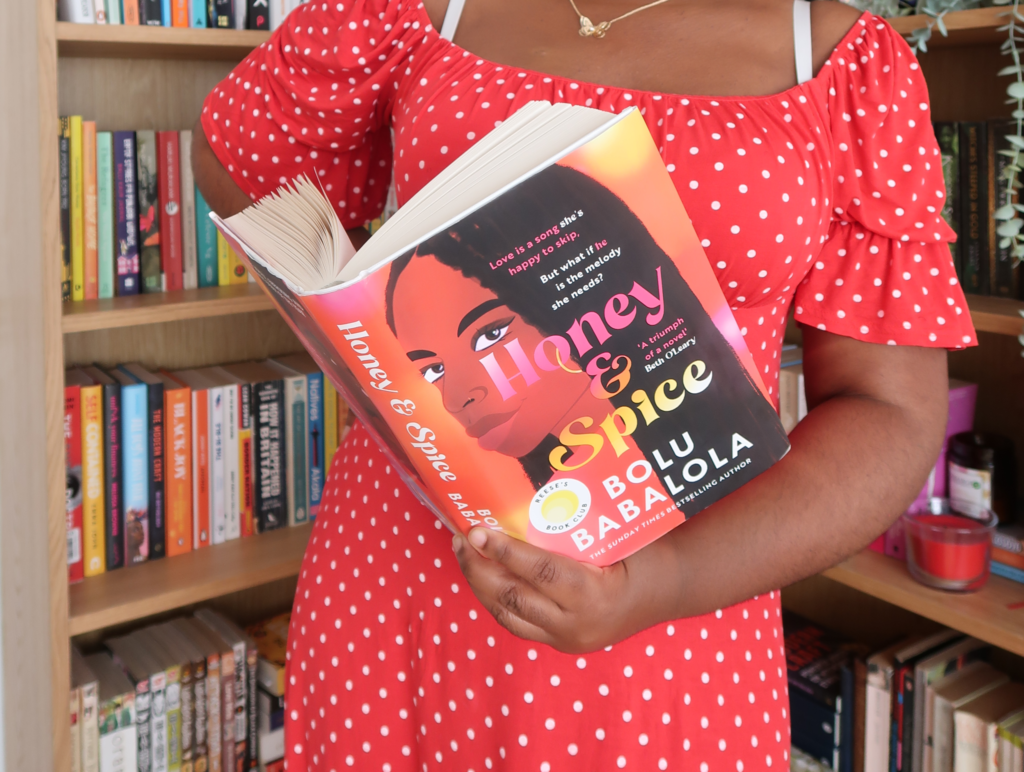

7) ‘HONEY AND SPICE’ by BOLU BABALOLA

A student falls for a guy who seems too good to be true in Babalola’s witty and charming debut novel

From the author of the bestselling short story collection Love in Colour comes this funny and charming debut novel, a university romcom geared towards young adult readers who like a touch of snark with their love stories. The plot of Honey & Spice is simple: Kiki is a self-controlled, ambitious and intelligent heroine who prides herself on being able to see through charming seducers, play them at their own game and emerge emotionally unscathed. One day, however, she meets a new student called Malakai. Handsome, clever, secure and nice, he must be too good to be true. Or is he exactly what he seems – and just what she needs?

Bolu Babalola with a Her colleague and fellow writer Caleb Azumah Nelson

The author teases out the traces of vulnerability and wariness beneath Kiki’s bravado

The book unfolds with the ease of a Netflix algorithm-generated miniseries. The usual romcom impediments arrive in the form of gossip, scheming, deception, bad timing and misunderstandings. But Bolu Babalola also teases out the traces of vulnerability and wariness beneath Kiki’s bravado, the mistrust and fear that underscore the female characters’ interactions with the young men in their lives. As Kiki confesses to Malakai: “You’re the only guy who’s ever held my hand without the intention of getting something from me. You just hold my hand to hold it. To hold me. Like you like doing it or something.”

Kiki makes for an entertaining narrator and the novel’s countless witty lines come mainly from her inner monologue. As the book opens, she is fleeing after a one-night stand with a fellow student who fancies himself as the campus Casanova but whose “50-thread count sheet scratched against my calves”. He embraces her cheesily in front of a mirror: “It only took a few seconds for his eyes to flit from me, from us, to his own reflection. His bottom lip had tucked in. It was honestly like a very uncomfortable threesome where two people were way more into each other than they were you.”

Immediately after this, Kiki meets Malakai and the real engine of the novel starts up. The story often drifts into a heavily Americanised snap’n’sass sitcom register, which sits oddly with its UK redbrick university setting, while the general descriptions, reported actions and exchanges between characters can be strained and clunky. However, the central couple have a beguiling sweetness and Babalola skilfully imbues their scenes with a tender innocence that is romantic.

Honey And Spice, a novel by Nigerian British writer Bolu Babalola is A Booktok Book Of The Year Award Winner and a Reese’s Book club pick. Set at a London University, it follows Kiki, am outspoken and ambitious student. The 2022 novel explores themes of culture and romance, providing an insightful look into the experiences of Black British Students.

INSTANT NATIONAL BESTSELLER • A REESE’S BOOK CLUB PICK • A TIKTOK BOOK CLUB PICK!!!

“Sexy, messy and wry, Honey and Spice more than delivers.” — New York Times Book Review

“A vibrant debut novel . . . Babalola is incisively funny, capturing the kick and sweetness of her title with her words.” — Entertainment Weekly

Named a Best Book of the Year by Time • Esquire • Vanity Fair • Oprah Daily • Cosmopolitan • Elle • Harper’s Bazaar • Southern Living • Buzzfeed • Women’s Health Magazine • AudioFile • Popsugar • and more!

Introducing internationally bestselling author Bolu Babalola’s dazzling debut novel, full of passion, humor, and heart, that centers on a young Black British woman who has no interest in love and unexpectedly finds herself caught up in a fake relationship with the man she warned her girls about

Sweet like plantain, hot like pepper. They taste the best when together…

Sharp-tongued (and secretly soft-hearted) Kiki Banjo has just made a huge mistake. As an expert in relationship-evasion and the host of the popular student radio show Brown Sugar, she’s made it her mission to make sure the women of the African-Caribbean Society at Whitewell University do not fall into the mess of “situationships”, players, and heartbreak. But when the Queen of the Unbothered kisses Malakai Korede, the guy she just publicly denounced as “The Wastemen of Whitewell,” in front of every Blackwellian on campus, she finds her show on the brink.

They’re soon embroiled in a fake relationship to try and salvage their reputations and save their futures. Kiki has never surrendered her heart before, and a player like Malakai won’t be the one to change that, no matter how charming he is or how electric their connection feels. But surprisingly entertaining study sessions and intimate, late-night talks at old-fashioned diners force Kiki to look beyond her own presumptions. Is she ready to open herself up to something deeper?

A gloriously funny and sparkling debut novel, Honey and Spice is full of delicious tension and romantic intrigue that will make you weak at the knees.

“A smart, sexy summer read, which hits your brain and your romance buttons in one shot.” — Los Angeles Times

“The ultimate summer romance . . . It’s got all the juiciest, most satisfying romance tropes, but in Babalola’s capable hands, the story feels fresh and unique.” — The Cut, New York magazine

“Divine summer reading. Hilarious, hot, and heartfelt. ” — Meg Cabot, #1 New York Times bestselling author

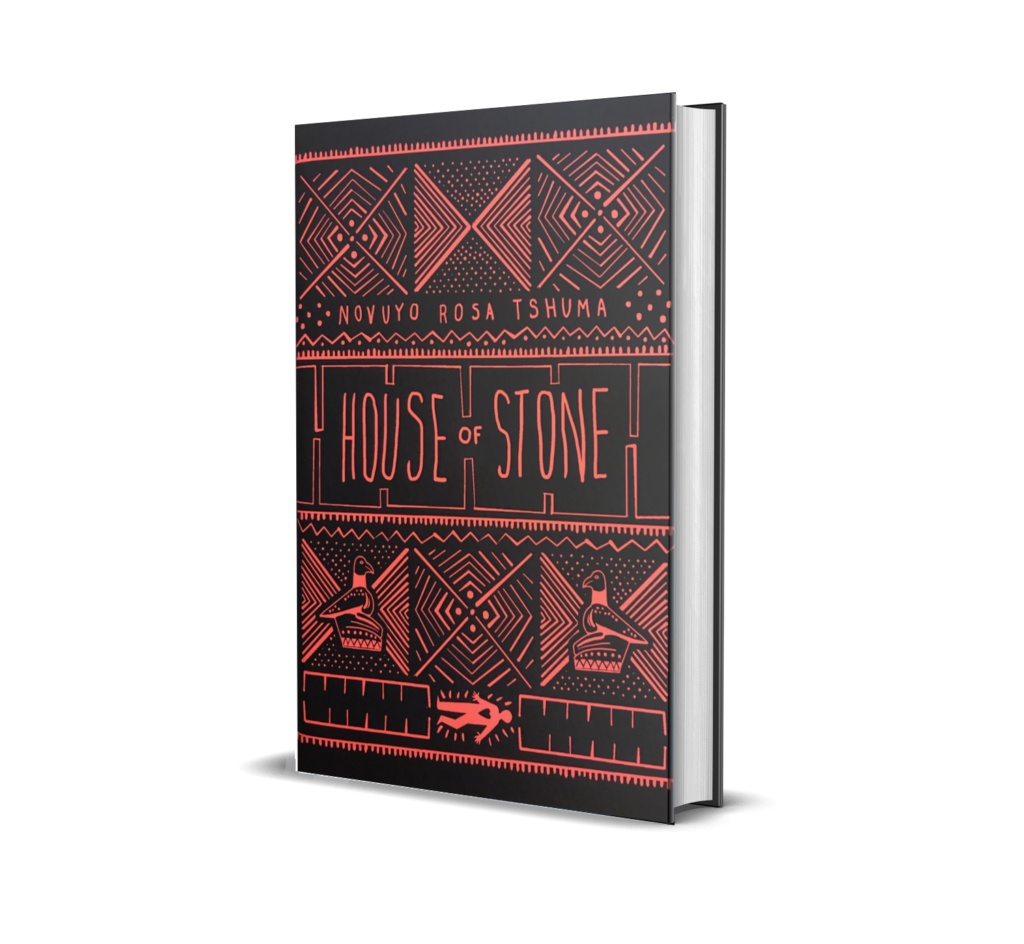

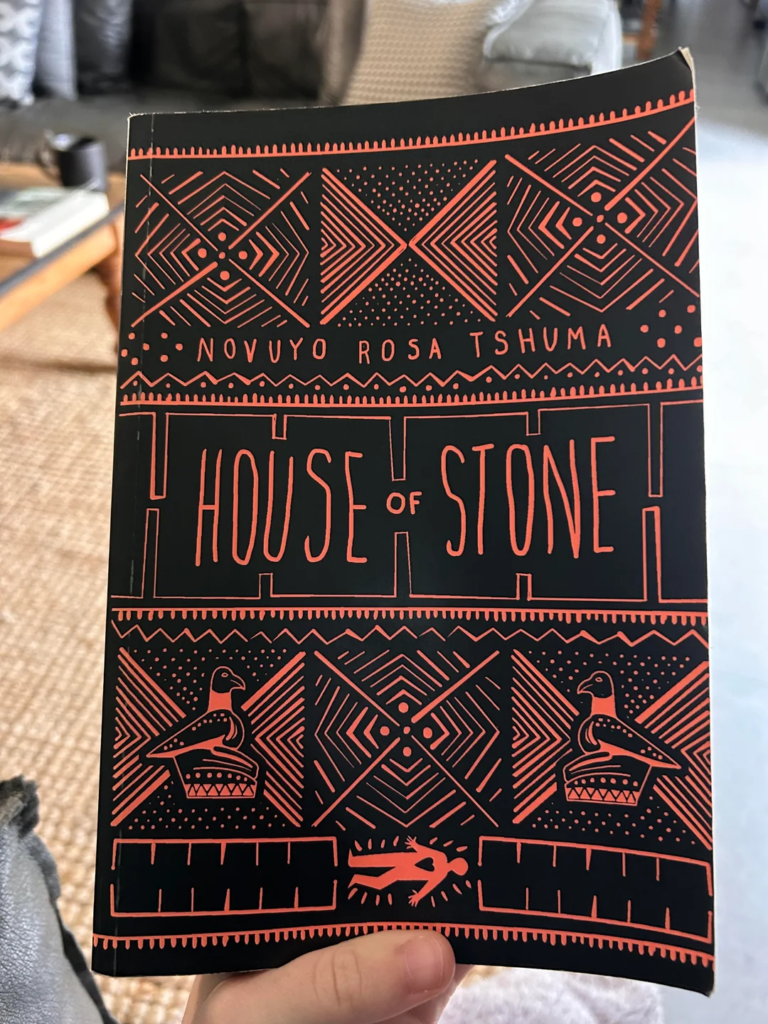

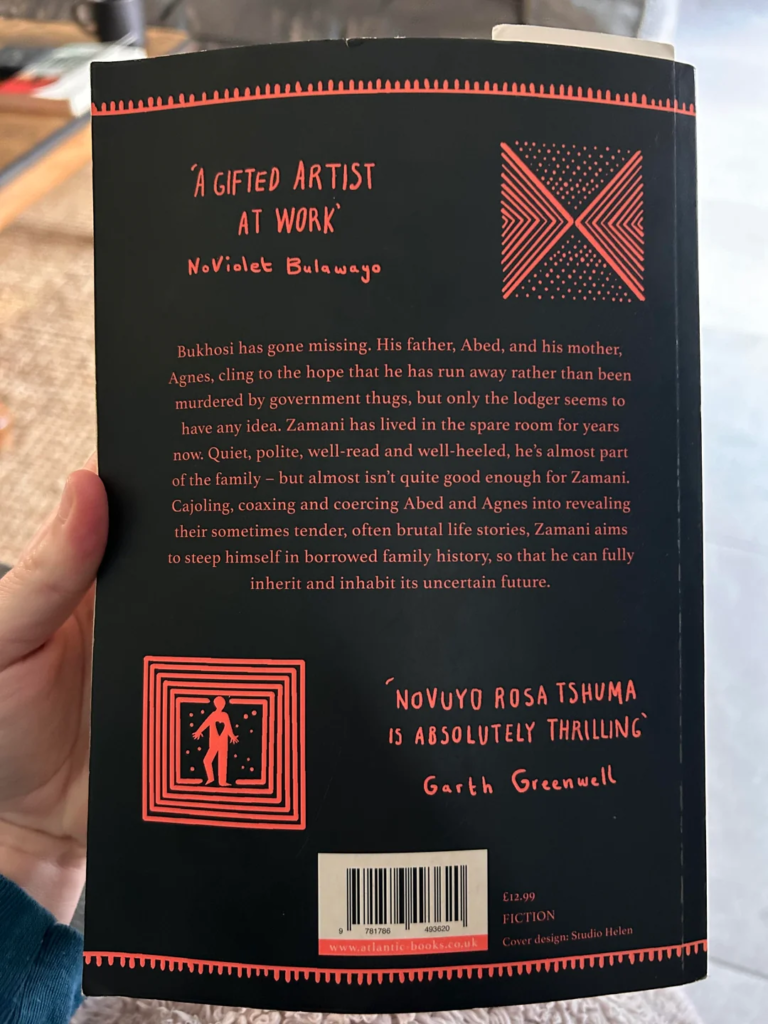

8) ‘HOUSE OF STONE’ by NOVUYO ROSA TSHUMA

Digest this!!! Do you need an epic story if you’re Zimbabwean? Your novel is called ‘HOUSE OF STONE’. Novuyo Tshuma gives just that in the 2018 Book that spans 50 years, shifting how we read, invent, and rediscover national histories. This books follows Zamani, a lodger in the Mlambo house, who helps the Mlambo’s search for their missing son Bukhosi, and in the process ends up inhabiting the home and their family history.

Remarkable … In his excess, [Zamani] has more in common with Saleem Sinai, the narrator of Salman Rushdie’s classic “Midnight’s Children”… in his usurpation of facts and stories [he] resembles Charles Kinbote in Vladimir Nabokov’s “Pale Fire.””

— Dinaw Mengestu, The New York Times

“* 2020 Lannan Foundation Fellowship Award

* Winner – 2019 Edward Stanford Travel Writing Award

* Winner – 2019 Bulawayo Arts Award for Outstanding Fiction

*Shortlisted – 2019 Orwell Prize for Political Fiction

*Shortlisted – 2019 Dylan Thomas Prize

*Shortlisted – 2020 Balcones Fiction Prize

*Longlisted – 2019 Rathbones Folio Prize”

Zamani is a psychopath. Not like Patrick Bateman in American Psycho, but the protagonist of Novuyo Rosa Tshuma’s affecting novel, House of Stone, is disturbing. He uses slyness, technology, gas lighting, propaganda, other people, expensive alcohol and magic potions to turn his landlords into his surrogate parents. He’s likeable in the pitying way you fall for Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Ugwu in Half of a Yellow Sun. He’s also charming in the annoying way that mad men can be.

House of Stone is a book of historical fiction. The backdrop of Tshuma’s book is the twenty first century agitation of the Mthwakazi secessionist group – a movement hinting at the separation of a portion of Zimbabwe into a country inhabited by the Ndebele people and commemorating Queen MuThwa, the first ruler of the Matebeleland region of Zimbabwe. The instigating force of the movement can be traced to the late 1980s genocide called Gukurahundi where Ndebele civilians were massacred. Zimbabwe experienced tribal friction after the loosening of the grip of the British empire. This script of one region of a country looking to amputate itself is common across the continent; from the formation the Republic of Biafra in the late 1960s by the Igbo people of Nigeria, to the Anyanya Rebellion of the late twentieth century between northern and southern regions of Sudan. Canibalisation seems to be the fate of most African liberation movements. The heady thrills of conquering an oppressor yield a voracious appetite for civil war and blood. Tshuma describes a horrific Gukurahundi scene in House of Stone, where a militia man with the nickname Black Jesus slices open a woman’s pregnant belly, spilling the contents onto the dusty grounds of the village he invades, before he sets a hut full of children ablaze. This is above and beyond the rape and dismemberment that assault the reader in a wrenching lesson in Zimbabwean history. The savagery belies twenty first century modernity. It is scary to think that contemporary violence and censorship in Zimbabwe refuse to harken to this bloody and recent past.

Zamani is an orphan. He was ferried by his Uncle Fani straight from the amniotic fluids of his mother’s womb and out of a concentration camp. Uncle Fani raises the boy, although Zamani does most of the work as he wades through Uncle Fani’s post-traumatic stress disorder which overflows in liquor and tears most nights. Zamani stays afloat until Uncle Fani’s death bed. On this last day Zamani catches square on the chest the anchor that is his birth story, which Uncle Fani throws at him in a last-ditch attempt to free himself from the memories of Gukurahundi. A dumbstruck Zamani goes on to organise himself a change of scenery in a paid internship as a nurse in London. Here he seemingly attains proclivities to literature, philosophy and poetry. Throughout the book he quotes the likes of Nabokov, Wittgenstein, Goethe, Bergson, Wordsworth and displays depth of character and history in sophisticated turn of phrase that denies his psychotic ways.

On returning to the old country, Zamani finds his Uncle Fani’s house now belonging to Abednigo and Agnes Mlambo. What is offered to the young man is a room in the backyard for rent (which, in the vivid language of Tshuma’s writing, is referred to as a pygmy room). He however seeks more than this. He sees a home; complete with a mom, a dad and a little bro in the landlords’ son Bukhosi. Zamani fantasises about a life where his identity is not anchored on a genocidal conception but a wartime love affair. He begins the process of excavating the back stories of his landlords in order to bury himself in their memories and co-opt their past as his. With his prized MacBook he literally re-writes the pluming family tree of the Mlambo’s. It’s an innocent enough venture. Until it’s not.

And that’s when Bukhosi goes missing. From then Zamani uses a variety of tactics and tricks to try and replace the absent son. The manipulation ranges from the sinister to the menacing. He takes advantage of Abednigo’s vulnerability by pushing him off the wagon, force feeding him whiskey and a magic potion called ubuvimbo. He stokes the embers of Abednigo’s domestic violence, placing Agnes in the line of fire so that he can swoop in to nurse her burns afterwards. This, all in order to get close enough to pry open their locked pasts and incept in there the idea of himself as a worthy replacement son. His efforts are espionage like when he entraps a nosy priest interfering in plans of erasing the memory of Bukhosi. The reverend is silenced by multiple photos on the front pages of a local newspaper carrying his rump peeking from the splayed legs of a Sister Gertrude, mid-coitus, curtesy of Zamani’s phone camera.

Tshuma couples Zamani’s charm and wit with a desperation and sensitivity that make you feel for the man. As with most psychopaths there is a severe insecurity that underlies a need for recognition. The slightest of rebuffs from either Abednigo or Agnes sets him off in streams of tears. A day after one of Abednigo’s Zamani induced drunken stupors, the young man tries to seduce the older man with tea laced with ubuvimbo. Abednigo, tired of the incessant presence of Zamani around the house, chases him away;

‘Can you go away. Can you just get out of here. Fuseki, bye bye!’

I cupped my ubuvimbo-laced tea and crawled away, back to the stifling confines of my pygmy room. I wept as I looked at our selfie on my Nokia, before stuffing it under my pillow. I don’t know what to do; I’ve been trembling all afternoon; I feel…lost. (p 95)

House of Stone uses the facility of domestic politics to display the global phenomenon of historical revisionism that plagues many African countries. The intentions of many an African leader who tries to induce a sense of unity after apartheid are noble, until those intensions extend themselves to the ambition of uniformity. At that point memories become weaponised. In London, Zamani meets a fellow Zimbabwean named Dumo. There the pair grow close as they imagine and conceive together the secession project. At home however, a rift grows between the two as Dumo’s revolution becomes dogmatic. Zamani finds it difficult to adopt wholesale some of Dumo’s polemics against the Shona people. For Dumo, the end holds all justifications. While Zamani is no Leon Trotsky or Joshua Nkomo, seeing the movement become the violence that it rebukes causes an undoing of his conviction. At a secret meeting, Dumo confronts a face he doesn’t recognise within the congregants. The stranger is identified as a Shona person. He is then summarily beaten. Escaping from the brawl, Zamani contemplates the end game of Dumo’s ambitions;

What kind of country would our Mthwakazi be? Would we continue the legacy of violence? Could we imagine into being the country as a Manifestation of Love? It was at this point, as I walked and thought the thoughts I thought … that I wondered what my own contribution to our hi-story had been, would be, could be. (p 339)

It is impressive that House of Stone is a debut novel. The book has a maturity about it, delivered in descriptive but crisp language with a style that is distinct. As an example, the quotidian enterprise and routine of Mama Agnes and her side hustle of selling oil, all while harbouring a personal secret and a traumatic past, is relayed with the mature energy that Nuriddin Farah injects in his 2018 novel North of Dawn – where the drama of elders is portrayed as only bubbling under the surface, never quite spilling out into epic scenes. But Tshuma takes this motif and upends it with dizzying twists. The book is also of cultural relevance, said to be a fitting companion to Panashe Chigumadzi’s These Bones Will Rise Again in relaying the anxieties of Zimbabwean youth about their country’s history and insistently problematic contemporary politics. And even though the book has not gotten wide enough distribution in her native country, Tshuma is assuredly at home on the pages of literary fiction.

“Novuyo Rosa Tshuma has written a towering and multilayered gem. House of Stone is one of the greatest-ever novels about Zimbabwe. What a timely, resonant gift.”

— NoViolet Bulawayo, author of WE NEED NEW NAMES

“To call [House of Stone] clever or ambitious is to do it a disservice – it is both, but also more than that…Tshuma is incapable of writing a boring sentence…She has managed to not only sum up Zimbabwean history, but also all of African colonial history: from devastating colonialism to the bitter wars of independence to the euphoria of self-rule and the disillusionment of the present. It is an extraordinary achievement for a first novel.” – Helon Habila, author of Oil on Water, for the Guardian

“With luminous language, Novuyo Rosa Tshuma explores the treacherous terrain of colonization and decolonization, remembering and forgetting, and love and betrayal. The result is a gripping account of revolution and its aftermath, both for a country and for one man.” – Viet Thanh Nguyen, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Sympathizer

“Written with biting humor, fierce insight, as well as tenderness towards each of the characters, House of Stone captures Mugabe’s Zimbabwe and a broader political environment both geographically and historically. Be prepared to laugh, shed tears and marvel at this young author’s debut.” – Yiyun Li, Vanity Fair

“Perhaps one of the most underrated novels of the year is Novuyo Rosa Tshuma’s House of Stone — an expansive tale that celebrates a nation through a central character. Were it written about any western country, this novel would have been much talked about, but we are talking Zimbabwe here. It is an ambitious and daring novel from a promising writer.” – Chigozie Obioma, the Guardian

“House of Stone is the novel devastated Zimbabwe had to have written. Now Novuyo Tshuma has written it. Bayethe to her scintillating talent! In the most original and fearless prose I’ve read in years, Tshuma’s scheming narrator, Zamani, reveals the personal and political disintegration that was Zimbabwe’s undoing.” – Tsitsi Dangarembga, author of Nervous Conditions

“House of Stone by Novuyo Rosa Tshuma is a literary, historical page-turner – a tall order that Tshuma achieves in this exceptional debut. There are several gasp-out-loud twists and a narrator who charms and offends in equal measure, even as the novel thoughtfully examines a brutal period in Zimbabwe’s history.” – Lesley Nneka Arimah, the Guardian

“House of Stone is a novel of such maturity, such linguistic agility and scope that you’ll scarcely believe it’s a debut. Tshuma has set her formidable talents to no less a subject than the emergence of Zimbabwe from the darkness and tumult of colonialism. It’s fierce and energetic right to the end, and whip smart to boot.” – Ayana Mathis, author of The Twelve Tribes of Hattie

“Tshuma’s House of Stone is a devastating and inviting piece of fiction that is earning its raves as a beyond notable first novel…Her book slips like sands through fingers through time and voice, masterfully condensing the history of Zimbabwe to the point where the back story is informative and provocative but not cumbersome…Tshuma deftly tells a story of colonization and decolonization both with a wide focus on the nation and a tight focus on a few people. The latter serves as a tragic microcosm of the former…Her balance between the tightest and the broadest focus is admirable and efficient.” – Andrew Dansby, Houston Chronicle

“No story I have read yet tells the story of marginalization of a people in Zimbabwe quite as well as House of Stone does. In weaving fact and fiction as effortlessly as she does, Tshuma makes us believe the truth of E.L.Doctorow that “There’s really no fiction or nonfiction; there is only narrative.” And what a painful narrative skillfully told House of Stone is. If Tshuma never writes another book (I really hope she does) she has entrenched her place into the history of literature with this book. A must read for lovers of history and good writing.” – Zukiswa Wanner, author of London-Cape Town-Joburg

“Tshuma’s debut novel is an astounding tapestry of national, familial and personal histories, woven together in one seamless narrative…The strength of [Zamani’s] voice carries House of Stone from one deception to the next, yet the heart of the novel remains a tender exploration of what it is to have firm roots in both family and country. House of Stone is a remarkable novel, using the intimacy of personal narratives to sculpt the history of Zimbabwe for the contemporary reader.Tshuma has shown a rare talent for creating blisteringly real characters, somehow cementing their authenticity in the unreliable histories narrated by Zamani.” – Beth Cochrane, The Skinny

“Tshuma’s writing is smart, original, feisty, brutal and gorgeous. She hits the perfect note on every single page in this gripping novel about history, belonging and power. This is the work of an incredible, incredible talent.” – Chika Unigwe, author of On Black Sisters’ Street

“House of Stone’ is that rare thing, a truly original work of art whose author’s risk taking pays off on the page. Zamani is a complex, compelling and ambiguous narrator. Utterly stunning.” – Tendai Huchu, author of The Maestro, the Magistrate and the Mathematician

“An enthralling novel that has it all: pathos, humour, and an insightful engagement with the history of Zimbabwe. With audacious style, Tshuma manages to step over the pitfalls that would swallow a lesser talent, and in so doing announces herself as a huge talent.” – Brian Chikwava, author of Harare North

“In this strong first novel for Zimbabwe-born Tshuma, narrator Zamani possesses many qualities of the classically defined unreliable narrator, particularly deception…A fascinating, often disturbing metaphor for Zimbabwe’s struggle to emerge from its colonial past and remember rather than erase its history; highly recommended.” – Library Journal, starred review

“Easily the best debut I’ve read this year, Tshuma’s novel is both hilarious and horrifying, filled with compassion, anger and despair.. [Zamani] is an unreliable narrator of the kind that deserves to be remembered up there with Humbert Humbert—a more recent comparison of a similarly playful, amoral narrator would be from Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathiser.” – Kim Evans, Culture Fly

“Reading House of Stone is like being punched in the stomach and tickled at the same time.” – Ranka Primorac

“House of Stone ties together intimate moments of love and family in the midst of revolution and turmoil, perfecting the balance of the personal and the political…a powerful meditation of identity, politics, and what makes a nation.” – Mya Alexis, Foreword

“Tshuma’s ambitious debut tells the story of the country’s bloody, complicated past—and also a carefully unfurling thriller evoking The Talented Mr Ripley and the film Six Degrees of Separation.” – Emerald Street

“A fantastic piece of literature that tells the Zimbabwean story through the story of Zamani an unreliable narrator seeking to weave his way into the love of the aggrieved family.” – Wisdom Mumera, Kalabash

‘“For all the violence Tshuma exposes in House of Stone, unavoidable when dealing with Zimbabwe’s history, she leavens the load with a sparkling exuberance, punctuated by passages of poetry and song, and an abundance of humour and tenderness.” – Linda Herrick, The New Zealand Listener

“Tshuma is our Zamani—feeding us the sweet nectar of historic lyricism, of which we can’t get enough.” – Books and Rhymes

“It is rare to encounter a character who is as terrifying as the above quoted Black Jesus, Tshuma’s masterful creation of inhumane terror…House of Stone is a fascinating blend of history, storytelling, violence, love, patriarchy, and unreliable narration.” – Tommi Laine, Helsinki Book Review

“This stunning novel weaves together the personal and national history in a compelling narrative about the bloody birth of modern Zimbabwe.” – Rabeea Saleem, Book Riot

Pulsing with wit, seduction, and dark humor, House of Stone is a masterful debut that explores the creative—and often destructive—act of history-making.

Amid the turmoil of modern Zimbabwe, Abednego and Agnes Mlambo’s teenage son has gone missing. Zamani, their enigmatic lodger, seems to be their only hope for finding him. As he weaves himself closer into the fabric of the grieving community, it’s almost like Zamani is a part of the family…

Zamani—one of the great unreliable narrators of contemporary world literature—knows that the one who controls the narrative inherits the future. As Abednego wrestles with alcoholism and Agnes seeks solace in a deep-rooted love, each must confront the burdens of history. Written with dark humor, wit, and seduction, House of Stone is a sweeping epic that spans the fall of Rhodesia through Zimbabwe’s turbulent beginnings, exploring the persistence of the oppressed in a young nation seeking an identity

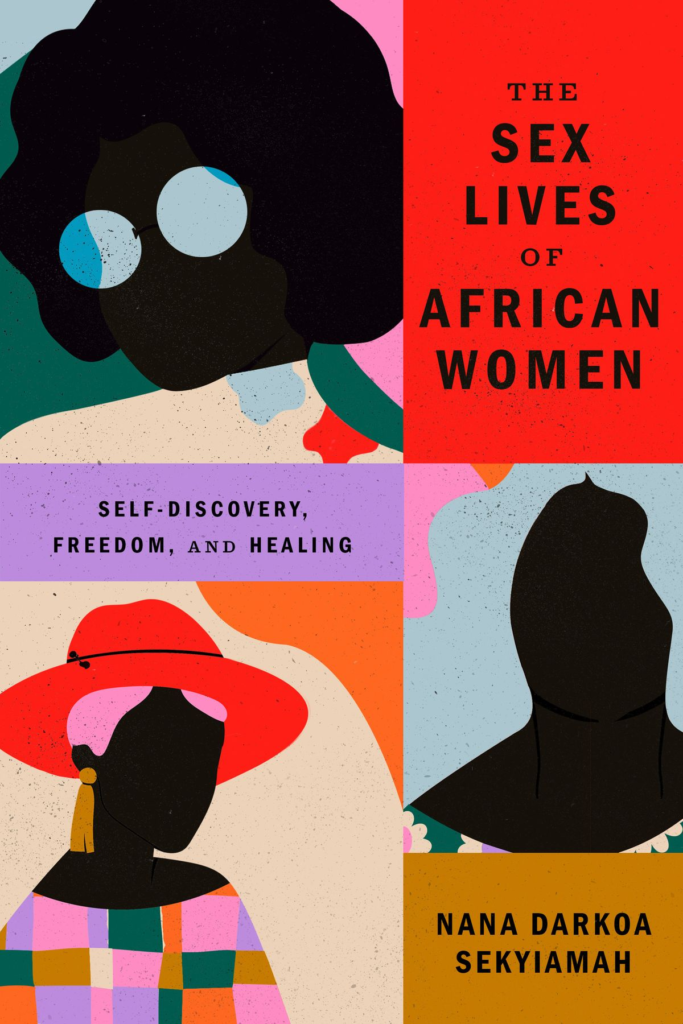

9) ‘THE SEX LIVES OF AFRICAN WOMEN’ by NANA DARKOA SEKYIAMAH

Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah, named on BBC’s 100 Women list of 2020, is a Ghanian writer and co-founder of the Award-Winning Blog, Adventures from the Bedrooms Of African Women. She has written widely on women’s sexuality and feminist subjects. Her anthology, The Sex Lives Of African Women was released in July 2021 to wide acclaim.

Ghanaian author Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah is the featured author in our series on what African writers are reading. Sekyiamah is a feminist writer and blogger. She co-founded the blog “Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women” and has written articles featured in The Guardian and Open Democracy. Her new book, titled The Sex Lives of African Women, contains groundbreaking interviews about women’s sexuality and freedom on the continent. Sekyiamah tells us what she is currently reading but also shares her to-be-read list, in addition to recommending books she’s read in the past and really loved.

Here is a book like none you will have read before. It draws on interviews conducted over six years by Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah – a Ghanaian feminist activist and award-winning blogger – with more than 30 black and Afro-descendant contributors from across the African continent and its global diaspora in Europe, the Americas and the Caribbean.

A conversation starter like Three Women but centering the experiences of women of color: a mellifluous chorus celebrating the liberation, individuality, and joy of African women’s multifaceted sexuality.

Thanks to her blog, Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women, Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah has spent decades talking openly and intimately to African women around the world about sex. For this book she spoke to over 30 African women across the globe while chronicling her own journey toward sexual freedom.

We meet Yami, a pansexual Canadian of Malawian heritage, who describes negotiating the line between family dynamics and sexuality. There’s Esther, a cis-gendered hetero woman studying in America, by way of Cameroun and Kenya, who talks of how a childhood rape has made her rebellious and estranged from her missionary parents. And Tsitsi, an HIV-positive Zimbabwean woman who is raising a healthy, HIV-free baby.

Across a queer community in Egypt, polyamorous life in Senegal, and a reflection on the intersection of religion and pleasure in Cameroun, Sekyiamah explores the many layers of love and desire, its expression, and how it forms who we are.

In these confessional pages, women control their own bodies and pleasure, and assert their sexual power. Capturing the rich tapestry of sex positivity, The Sex Lives of African Women is a singular and subversive book that celebrates the liberation, individuality, and joy of African women’s multifaceted sexuality.

It both documents and legitimises the desires and sexuality of African women, beyond every conceivable stereotype, in three sections: self-discovery, freedom and healing – and if the first two feel more substantial than the third, that reflects real life, just as at the heart of it all is the desire for freedom to be oneself. No topic is off limits as these conversations reveal and explore similarities and differences, about questioning societal norms, religious edicts, confronting the trauma of sexual abuse and searching for new narratives and identities on the path towards wholeness.

The women speak openly and invariably for the first time about their experiences of sex and relationships as they seek to claim individual agency, however that expresses itself. They share emotion-filled stories with honesty, addressing everyday personal dramas within the wider context in which self-worth and confidence are affected by racism and patriarchy, with revolution in the streets and revolution in the sheets being two sides of the same coin.

The quest for self-discovery may involve a literal journey, moving to another country for the sake of love, or an exploration of the unfamiliar. Bravery and vulnerability are apparent in equal measures. Growing up as the offspring of monogamous parents can be tough preparation for the challenge of being one of several wives. Heterosexuality and celibacy are just two of a vast range of options. While one participant is “pansexual, polyamorous and kinky”, others identify as bisexual, transexual, queer, or simply “a work-in-progress sexually free woman”.

With sensitivity, this book has facilitated astonishing breaking of silences. The ending may not be “and they lived happily ever after”, but if the conversations have proved therapeutic for those involved, that is its own reward. One piece ends with the observation: “I’ve learnt to ask myself every day: Are you happy today? And if the answer is no I make a change.”

Sekyiamah has delivered an extraordinarily dynamic work, true to her own precept that “Freedom is a constant state of being … that we need to nurture and protect. Freedom is a safe home that one can return to over and over again.”

“Ghanaian activist and blogger Sekyiamah debuts with a dazzling series of soul-searching and taboo-breaking conversations with women throughout Africa and the diaspora about relationships, sex, and identity…Marked by the diversity of experiences shared, the wealth of intimate details, and the total lack of sensationalism, this is an astonishing report on the quest for sexual liberation.” – Publishers Weekly (starred review)