In the spirit of Afrofuturism, a cultural practice which imagines Black people living full lives with the agency in both the present and future, the following list provides rich examples of Black people literally writing their own futures, and maintaining control over narratives both real and fictitious.

Perhaps ironically, while the genre is often centered on alternate realities, the work of many Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy writers focuses on creating fictional worlds with diverse characters that encourages readers to think critically about our actual realities. They do so often, by providing social commentary that resonates with the reader through imaginative delivery.

Ask anyone who’s ever read Octavia Butler’s Kindred and we’re sure they can vividly recall stepping into it’s surreal, time-travelling world. It accomplishes what all good science-fiction does: it transports the reader somewhere different, somewhere outside of the ordinary. While the fantasy and sci-fi genres are reserved for white males, there have been several black writers who have followed in Butler’s footsteps to produce classic works within the genre. From N.K Jemisin with her celebrated inheritance Trilogy to novels from the multiple Hugo award winning Nigerian author Nnedi Okorafor, writers from Africa and the diaspora, have consistently crafted some of the most illuminating and visionary works in the literary space.

From the earlier works of Fiction, to more contemporary titles, below are Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Novels (Some of which the PUBLISHING RIGHTS HAS BEEN BOUGHT AND ADAPTED FOR MOVIE CREATION) that will take you on a journey in Another Dimension.

1) FUTURE LAND by WALTER MOSLEY

Future Land consists of 9 short stories, which takes place in a stratified dystopian universe ruled by a greedy elite, and sadly doesn’t sound too far off from current realities in some societies. Each story in the anthology offers satirical commentary on a specific social ill- from Capitalism, to War on Drugs to the Prison Industrial Complex, offering new ways to understand such issues.

Futureland is a series of nine loosely connected short pieces of science fiction by writer Walter Mosley. The novel is set in a postcyberpunk dystopian universe populated by humans living in a shellshocked, unfairly stratified society overseen by super-rich technocrats.

A generation from now, things aren’t much different from today: The drugs are better, the daily grind is worse. The world’s knowledge fits on a chip in your little finger, the Constitution doesn’t apply to individuals, and it’s a crime to be poor.

— Walter Mosley, Warner Books 2001

Stories

Whispers in the Dark – Introduces the early life of one Ptolemy Bent, a young black child who has the greatest IQ the world has ever known, and the purest heart possible in the world he is born into. Because of his IQ, the government wants to take him away from his family to give him education. To prevent this, his uncle sells his organs in order to afford proper education for Ptolemy (known as Popo). The book ends with Ptolemy uploading the digital consciousness of his grandmother and uncle into radio waves as they were both sick. This section ends with him being sent to jail.

The Greatest – Fera Jones rises to the challenge and becomes the first female Universal Boxing Authority World Champion. Along the way, she endures the stress of a risky operation for her father and trainer, Leon Jones, who is addicted to the lethal fantasy-dream drug pulse, which inevitably kills the user as the brain degrades. Pell Lightner, a young man born to permanently unemployed parents, takes up the role of her coach, and gets her through the toughest match of her career.

Doctor Kismet – An interview between the CEO of MacroCode International, the world’s most powerful corporation, and one of the leaders of the Sixth Radical Congress, a movement to strengthen the positions of African-Americans in world society.

Angel’s Island – The tale of a prisoner on the world’s largest privately owned prison and how he came to expose its dark secrets.

The Electric Eye – Folio Johnson is the lead in this more traditional detective following the “last private detective in New York”. Folio is hired to investigate the mysterious deaths of members of an elite Neo-Fascists think tank group known as the International Socialists, “The Itsies”.

Voices – Professor Jones (Fera Jones’, from ‘The Greatest’, father) hears voices in his head after undergoing a brain tissue transplant. His doctor reassures him that it is simply the foreign tissue becoming part of him. Jones meets a little girl in a park who he shows a fatherly affection for, however her existence is eerie. Similar scenes play out throughout the story, making him question what is real and what are dreams, maybe even echoes of his past drug addiction.

Little Brother – Frendon Blythe is a young activist, who must stand courtroom trial for the death of a policeman in Common Ground, where the defendant can afford neither an attorney nor a judge. He is thus tried and matches wits with a judicial automaton programmed with the minds of 10,000 legal experts, trying to win the sympathy of an AI jury of 10,000 digital consciousnesses.

En Masse – Neil Hawthorne, a young man living in a future New York City, works as a “prod,” a job which sends him into nervous panic attacks–these panic attacks could get him diagnosed with acute Labor Nervosa, losing him his job and sending him into permanent unemployment. Then, Neil is suddenly assigned to the GEE-PRO-9 program. With an amazing view of the East River, lax rules, and stimulating development projects, this new program makes Neil immediately suspicious; he becomes anxious that his management is testing him.

The Nig in Me– A biochemically engineered disease–meant for coloured people by the white supremacist technocrats, but sabotaged by a team of activists in En Masse–ravages the world. The only people who are spared are those with “at least 12.5% African DNA.”

2) THE HUNDRED THOUSAND KINGDOMS by N.K. JEMISIN

The HUNDRED Thousand Kingdoms is the first book in the celebrated author’s The Inheritance Trilogy. The fantasy novel-which won Jemisin The Locus Award for Best First Novel in 2011- follows protagonist Yeine Darr, who is named heir to the city of the Sky. However, she later finds that the city has also been promised to the present ruler’s niece and nephew, which causes an intense and often dangerous rivalry between the three characters as they fight for the throne.

The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms is a 2010 fantasy novel by American writer N. K. Jemisin, the first book of The Inheritance Trilogy. Jemisin’s debut novel, it was published by Orbit Books in 2010. It won the 2011 Locus Award for Best First Novel and was nominated for the World Fantasy, Hugo, and Nebula awards, among others. Its sequel, The Broken Kingdoms, was also released in 2010.

Yeine Darr, mourning the murder of her mother, is summoned to the magnificent floating city of Sky by her grandfather Dekarta, the ruler of the world and head of the Arameri family. As Yeine is also Arameri (though estranged due to the circumstances of her birth), he names her his heir but has already assigned that role to both his niece and his nephew, resulting in a thorny three-way power struggle. Yeine must quickly master the intricacies of the cruel Arameri society to have any hope of winning. She is also drawn into the intrigues of the gods, four of whom dwell in Sky as the Arameri’s powerful, enslaved weapons. With only a few days until the ceremony of the Arameri succession, Yeine struggles to solve her mother’s murder while surviving the machinations of her relatives and the gods.

Yeine Darr was born to Kinneth Arameri, who was heir to the Arameri throne but abdicated twenty years before the start of the story to marry Yeine’s father, a Darre man. Kinneth was disowned by Dekarta (patriarch of the ruling Arameri family), and Darr blacklisted by the Arameri (throwing the country into a crippling economic crisis) as a result.

The day she arrives, she meets T’vril, the palace steward, who is also an Arameri (although lower-ranked); the entire palace staff down to the floor cleaning servants is Arameri. This is because only Arameri are permitted to pass a night in Sky, for reasons that T’vril does not immediately explain. T’vril attempts to get Yeine to Viraine—the palace scrivener—to be “marked” as an Arameri before nightfall. However, Scimina, one of the other potential heirs, finds them first. Because Yeine lacks the mark, she unleashes Nahadoth, one of the Arameri’s captive gods, on Yeine.

Yeine flees and is assisted by Sieh, another of the captive gods. Before they can escape, Nahadoth catches up and attacks Sieh, whereupon Yeine stabs Nahadoth to apparent death with her knife. Nahadoth kisses her before he falls, saying he has been waiting for her, much to Yeine’s confusion. Being a god, Nahadoth returns to life shortly afterward. Yeine then meets the other gods—and quickly realizes that they, like the Arameri, have frightening plans for her.

Yeine, however, has her own agenda: still in mourning, she has come to Sky to determine who may have killed her mother before the start of the story. While attempting to forge an alliance with Relad, her cousin and the other potential heir, she also seeks out answers to the mystery of her mother’s past. This leads Yeine to terrifying revelations about herself, her world’s history, and the gods themselves.

As the day of the succession ceremony approaches and Yeine finds herself left with few options, she chooses to ally with the Enefadeh—even though Nahadoth warns her that they want her life in exchange for their assistance. Determined to learn the truth about her mother even if she dies in the process, she agrees to the gods’ bargain. She also begins brief liaisons with first T’vril, then Nahadoth himself, the latter of whom seems equally drawn to her, though his motives are unclear.

The story culminates with the Arameri Ceremony of the Succession, at which Itempas himself—the Skyfather, ruler of the universe—appears, and Yeine makes a fateful choice.

Characters

The following main characters appear in the book:

- Yeine – Yeine Darr (the short form of her full name, which is “Yeine dau she Kinneth tai wer Somem kanna Darre”) is half Arameri and half Darre. Her mother, formerly the Arameri heir, has been murdered when the story opens, and part of Yeine’s goal in the city of Sky is to avenge her death. Yeine is the chieftain, or ennu, of the Darre—an hereditary/figurehead role, though with some representative power. She is considered a barbarian by the Arameri.

- Nahadoth – The Nightlord, otherwise known as the god of night, chaos, and change, is the eldest of the Gods and the most dangerous. He appears in different guises.

- Itempas – The god of law, order, and light, Itempas is worshipped as the Skyfather the world over.

- Enefa – The goddess of twilight, dawn, balance, life, and death, she was murdered several thousand years before the start of the tale.

- Sieh – The Trickster, a godling who chooses to take the form of a nine-year-old boy. In reality he is the eldest of all the godlings, several billion years old. He befriends Yeine for inexplicable reasons.

- Kurue – Another godling, the goddess of wisdom, and the apparent leader of the enslaved gods.

- Zhakkarn – Another godling, the goddess of war and battle.

- Dekarta – As the head of the Arameri family, Dekarta is the “uncrowned” ruler of the Hundred Thousand Kingdoms and Yeine’s grandfather. He summons Yeine to Sky at the beginning of the story, and names her one of his heirs.

- Scimina – One of Yeine’s cousins, a fellow heir. The apparent primary antagonist of the story.

- Relad – Scimina’s younger twin brother and the other potential heir. He is a bitter drunkard, but Yeine’s best chance for an alliance in order to survive the contest of heirs.

- T’vril – A half-blood like Yeine, he is the palace steward. He quickly becomes one of Yeine’s allies.

- Kinneth – Kinneth was Dekarta’s only child, Yeine’s mother.

- Viraine – He is the palace scrivener, a scholar who studies the gods’ language; this language permits him to work limited magic. He too helps Yeine, though his motives are unclear.

Reception

The book was well received. It won the 2011 Locus Award for Best First Novel and the Romantic Times Reviewers’ Choice Award. It was shortlisted for the 2010 Tiptree Award, the 2011 Crawford Award, and was nominated for the 2010 Nebula Award for Best Novel, the 2011 Hugo Award for Best Novel, the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel, the 2011 David Gemmell Legend Award, and the Goodreads Readers’ Choice Award for Fantasy.

3) REDEMPTION IN INDIGO by KAREN LORD

In her debut novel, Barbadian writer, Karen Lord pens a humorous, fantastical tale about a woman, who after leaving her gluttonous husband, is granted a magical stick that allows her to control the world’s forces. This powers indeed makes her a target of a selfish witch doctor who doesn’t want these supernatural capabilities to be shared with anyone else. With it’s rich magical tales, the novel draws on common themes from Senegalese folklore.

Karen Lord’s debut novel is an intricately woven tale of adventure, magic, and the power of the human spirit. Paama’s husband is a fool and a glutton. Bad enough that he followed her to her parents’ home in the village of Makendha—now he’s disgraced himself by murdering livestock and stealing corn. When Paama leaves him for good, she attracts the attention of the undying ones—the djombi— who present her with a gift: the Chaos Stick, which allows her to manipulate the subtle forces of the world. Unfortunately, a wrathful djombi with indigo skin believes this power should be his and his alone.

Bursting with humor and rich in fantastic detail, Redemption in Indigo is a clever, contemporary fairy tale that introduces readers to a dynamic new voice in Caribbean literature. Lord’s world of spider tricksters and indigo immortals is inspired in part by a Senegalese folk tale—but Paama’s adventures are fresh, surprising, and utterly original.

Why did I read this book: A moment of truth (and shame): I don’t remember when or why I bought this book – I seem to recall vaguely a review talking about this book featuring a trickster character and since I love tricksters, it is safe to say this might have been the reason for buying it. Why did I read it now? I recently stumbled upon this book when organising my Kindle folders and it looked good and then I googled it only to learn that it was a World Fantasy Award Nominee for Best Novel (2011) and it won the Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for Adult Literature this year. I needed no more incentive.

Review:

There is a point in Redemption in Indigo when the omniscient narrator says that “tales are meant to be an inspiration, not a substitute”. It is a meaningful line and one that sticks around longer than expected. It is one line among many others within this novel that provokes the reader and stimulates a certain level of engagement about the nature of storytelling and reader’s expectation. It is also an appropriately self-descriptive line because Redemption in Indigo is inspiring.

The story draws inspiration from a folk tale from Senegal about a heroine named Paama. Her story though is only but a starting point for Karen Lord to construct her own fantastical tale – one that includes djombi (spirits that are mainly personifications of ideas or forces such as change or patience), tricksters and a stick that can control the forces of chaos.

Paama is a wonderful cook and her husband Ansige is a glutton. You would think theirs is a match made in heaven but Ansige’s gluttony is accompanied by intolerance, arrogance and stupidity and finally after years of endurance, Paama leaves Ansige. Two years later, the man is finally moved to go in search of his wife, finding Paama living with her parents in her childhood home. Ansige’s penchant to get into silly situations and create a myriad of problems is equivalent only to Paama’s awesome efficiency with dealing with them. It is this mixture of endurance and brilliance that brings Paama to the attention of a djombi in search of someone to carry the Chaos Stick after it was seized from its previous owner – another djombi with indigo skin who misused its power but still insists he is its rightful owner and will do anything in his power to get it back.

What ensues is an extremely elaborate tale that deals with very human feelings against the backdrop of universal- sized problems in a sublime combination of the immediate (and short-lived) and the everlasting (and immortal). On the one hand there lies Paama and her family, their village, their prospects in life. There are dreams to be lived and love to be had as well as hurdles to be overcome. Paama is a brilliant heroine, resilient, brave, vulnerable and uncertain. This is someone who buries her tears and carries her burden and deals with her problems the best way she can.

On the other hand, the immortal djombi and the trickster watch, mingle and affect and are in turn, affected by all this humanity. The principal plot is that between the indigo djombi and Paama and their way of using (or not) the Chaos Stick. The djombi at first shows a disregard for human beings (reason of his downfall) that is equal to Paama’s esteem for them although her gaze turns out be perhaps too short-sighted which is, of course, only to be expected. It is ironic actually that this puny, short-lived human is given the stick by the personification of patience. There is an undeniable gravitas to this story and yet it is deceptively light due mostly to its narrative. As great as the story and the characters are, the omniscient narrator is what tips the scale and sets this story into awesome territory. The narrator tells this story in a way that reminisce oral traditions, that reminds of old times, that invites the reader to come closer and to listen carefully. It is a narrator that is utterly familiar and incredibly original at the same time and equal parts funny, opinionated and wise:

I told you from the very beginning that it was a story about choices – wise choices, foolish choices, small yet momentous choices – for with choices come change, and with change comes opportunity , and both change and opportunity are the very cutting edge of the power of chaos. And yet as the undying ones know and the humans too often forget, even chaos cannot overcome the power of choice.

Redemption in Indigo is a brilliant little gem of a novel, as close to perfect as storytelling can be. It is hard to believe that such an intricate tale could be told in just about 200 pages. It is even harder to believe that this is Karen Lord’s debut given how self-assured the narrative is. But it is extremely easy to see how this book has earned such well-deserved admiration, mine included.

Notable Quotes/ Parts: From the opening pages:

Introduction

A rival of mine once complained that my stories begin awkwardly and end untidily. I am willing to admit to many faults, but I will not burden my conscience with that one. All my tales are true, drawn from life, and a life story is not a tidy thing. It is a half-tamed horse that you seize on the run and ride with knees and teeth clenched, and then you regretfully slip off as gently and safely as you can, always wondering if you could have gone a few metres more.

Thus I seize this tale, starting with a hot afternoon in the town of Erria, a dusty side street near the financial quarter. But I will make one concession to tradition.

…Once upon a time—but whether a time that was, or a time that is, or a time that is to come, I may not tell—there was a man, a tracker by occupation, called Kwame. He had been born in a certain country in a certain year when history had reached that grey twilight in which fables of true love, the power of princes, and deeds of honour are told only to children. He regretted this oversight on the part of Fate, but he managed to curb his restless imagination and do the daily work that brought in the daily bread.

Today’s work will test his self-restraint.

4) MY LIFE IN THE BUSH OF GHOST by AMOS TUTUOLA

This 1954 novel by Amos Tutuola- the Nigerian author of The Palm Wine Drunkard- is a collection of narratives about a young boy who enters the wilderness after being abandoned by his family. During his journey, he comes in contact with various forces and spirits that shape and alter his path. Interesting fact: the debut 1981 album by Brian Eno and David Byrne, is named after the novel, though they admitted to not having read it upon the time of the album’s release.

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts is a novel by Nigerian writer Amos Tutuola, published in 1954. It tells the story of a young West African boy who becomes lost in the wilderness, known as the bush, after fleeing from slave traders with his elder brother. The novel is presented as a collection of related narratives, although not always in chronological order, which adds to its surreal and dreamlike quality.

The protagonist, who remains unnamed throughout the book, is portrayed as young and inexperienced, unaware of the dangers that lurk in the bush, including ghosts and spirits that pose great peril to mortals. As he navigates through this strange and mysterious place, he encounters a series of bizarre and often nightmarish beings and experiences. Tutuola’s use of English, from the perspective of a naive and youthful narrator, creates a unique and authentic voice that adds to the novel’s charm and intrigue.

Like Tutuola’s earlier work, The Palm-Wine Drinkard, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts is heavily metaphorical and autobiographical. Tutuola draws on his own experiences and African folklore to craft a tale that explores themes of identity, culture, and the human condition. The novel’s disjointed narrative structure and fantastical elements, reminiscent of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, lend it a sense of otherworldliness and make it a captivating read that challenges traditional notions of storytelling.

Critical reception

Time magazine selected My Life in the Bush of Ghosts as one of its “100 Best Fantasy Books of All Time”.

The title was Nominee for narrative Strainers in 1984 by Premio Grinzane Cavour.

Tributes

The title of the 1981 album My Life in the Bush of Ghosts by David Byrne and Brian Eno was taken from this novel.

5) BROWN GIRL IN THE RINGS by NALO HOPKINS

In this 1998 “Urban Fantasy” novel Jamaican-Canadian writer, Nalo Hopkins; imagines a futuristic, dystopian version of downtown Toronto, where poverty and crime are rampant. The city is under a control of a drug-lord named Rudy and the heroes of the story are a young Black woman named Ti-Jeanne and her grandmother who use magic and herbal spells to help solve the city’s many social ills.

Brown Girl in the Ring is a 1998 novel written by Jamaican-Canadian writer Nalo Hopkinson. The novel contains Afro-Caribbean culture with themes of folklore and magical realism. It was the winning entry in the Warner Aspect First Novel Contest. Since the selection, Hopkinson’s novel has received critical acclaim in the form of the 1999 Locus Award for Best First Novel, and the 1999 John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer.

In 2008, the actress and singer Jemeni defended this novel in Canada Reads, an annual literary competition broadcast on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

The setting of Brown Girl in The Ring is post-apocalyptic in nature. The story takes place in the city core of Metropolitan Toronto (Downtown Toronto) after the economic collapse. Riots of the past have caused the inner city of Toronto to collapse into a slum of poverty, homelessness, and violence. While the elite and city officials have fled to the suburbs, children are left to fend for themselves and survive on the streets. As a consequence of the Riots, Toronto is isolated from other satellite cities in the surrounding Greater Toronto Area (North York, Scarborough, Etobicoke) by roadblocks and Lake Ontario has become a mudhole. Disappearances and murder are not uncommon, and everyone is left to either fend for themselves or bind together to provide support for each other.

In the twelve years since the Riots, the city is now ruled by a criminal mastermind, Rudy Sheldon, and his posse of criminal thugs. Rudy is commissioned to find a heart for the Premier of Ontario, who needs a heart transplant. Normally, the Porcine Organ Harvest Program is used, but the adviser of Premier Catherine Uttley encourages her to deem the program “immoral” and make a public statement of preference for a human donor instead.

Hopkinson then introduces the heroine of the story, and a very different perspective of life in the outskirt of the city is seen. Ti-Jeanne, the granddaughter of Gros-Jeanne, is struggling with different problems than street survival. Having recently given birth to a baby boy, Ti-Jeanne is forced to move back in with her grandmother to care for her child as a single mother; the child’s father, Tony, suffers from addiction and is a member of the posse. While she loves her Mami, she has difficulty seeing the importance of her grandmother’s spiritualism and medicinal work, and is frightened by her visions of death. Gros-Jeanne has gone to great lengths in the past to share her culture with her family, but has continuously been pushed away by her daughter and granddaughter. In the community, she is a well-respected apothecary and spiritualist who runs an herbal and medicine shop.

Paths begin to cross when Tony is called upon by Rudy. Hopes of leaving his criminal life behind and reconnecting with his love, Ti-Jeanne, are shattered when the threats from the posse leader begin to loom over him. Tony must perform a horrific murder in order to obtain a heart that will save the life of one of the city’s elite. The situation only gets worse when he involves his relationship with Ti-Jeanne and Gros-Jeanne with his business with the posse. He arrives on Gros-Jeanne’s doorstep asking for protection, and Ti-Jeanne convinces her to help him flee the city without harm.

The magic comes alive for the rest of the novel when Tony seeks help from the spiritualism of Gros-Jeanne. In attempts to save Tony, Ti-Jeanne performs the rituals alongside her Mami and accepts her father spirit. When plans go awry, Tony makes a rash decision that forces Ti-Jeanne to be the one to save herself and the city from Rudy’s evil spiritual acts.

Later in the novel, Rudy is revealed to be Ti-Jeanne’s grandfather, Gros-Jeanne’s husband. It turns out that Rudy was an abusive husband and Gros-Jeanne kicked him out and found a new lover, named Dunston, and since Rudy has been vengeful.

Meanwhile, Rudy summons the Calabash Duppy spirit and commands the duppy to kill Gros-Jeanne, Ti-Jeanne and Tony, who was sent to kill Gros-Jeanne and take her heart for Premier Uttley. It’s revealed that the duppy is Mi-Jeanne (Ti-Jeanne’s mom).

In the CN Tower, Rudy sets the Calabash spirit on Ti-Jeanne who has come to confront him after Tony killed Gros-Jeanne. Ti-Jeanne is trapped and injected with Buff, a drug that paralyzes her. While in a state of paralysis, Ti-Jeanne slips into an “astral” state or spirit state, and calls upon the ancestor spirits to help her. They kill Rudy by allowing the weights of every murder he has done fall on him.

Meanwhile, Premier Uttley’s new heart (Gros-Jeanne’s heart) attacks her body. Eventually, it takes over her spirit and when she wakes up from the surgery, she has a change of mind about human heart donorship and declares that she will make an attempt to help Toronto return to a rule of law by funding small business owners.

On Gros-Jeanne’s Nine Night event, all her friends arrive to help out, and so does Tony. Ti-Jeanne has trouble forgiving him for killing Gros-Jeanne, but Jenny tells her “he wants to do penance.” She lets him into the event to say goodbye to Gros-Jeanne and is surprised that Baby doesn’t cry around him anymore. It ends with Ti-Jeanne sitting on her steps, thinking of what she’ll name Baby, who is possessed with the spirit of Dunston, Gros-Jeanne’s former lover.

Ti-Jeanne’s personal growth throughout the novel is evident in her attitude toward her elders, culture, and outlook on life. Through acceptance of her ancestry and culture, she finds power and support to overcome steep odds and end the horrific violence of the posse and their heinous leader, despite her personal connection to the man who took her mother away from her at a young age. The story closes with hope, Ti-Jeanne’s victory is monumental, and the stolen heart possesses the power to permanently change the city of Toronto for the better.

Themes

Themes of feminism in women of color and the use of magic, “Obeah,” or seer women are prevalent throughout this novel. Nalo Hopkinson presents strong female characters who take control of their fate to make change in the world. Her novel is a work of feminist science fiction and shows a realistic perception of the struggles women face as single mothers as well as the struggles women with different cultural beliefs face in society. However, it shows their ability to use their culture, background, and experiences as women to overcome obstacles and show the true strength women possess. In addition, the themes of community and money are seen with the street children.

Reception

F&SF reviewer Charles de Lint declared Brown Girl “one of the best debut novels to appear in years,” although he acknowledged initial difficulty with the novel’s “phonetic spellings and sometimes convoluted sentences.”

Film adaptation

After fifteen years of trying to adapt the novel to film, Canadian director Sharon Lewis decided to create a prequel instead. The film, titled Brown Girl Begins, was filmed in 2015/2016, and premiered in 2017 before going into general theatrical release in 2018.

6)DARK MATTER: A CENTURY OF SPECULATIVE FICTION FROM THE AFRICAN DIASPORA, “edited” by SHAREE THOMAS

This anthology is a great introduction to the world of Black Magic Realism. It’s a collection of fantasy, horror and Sci-Fi prose written by black intellectuals like W.E.B Du Bois- whose short story The Comet, is one of the book’s standouts-and some of the biggest names in the genre, including Nisi Shawl, Ishmael Reed, Octavia Butler and More.

If you find yourself intrigued by the genre, a great place to start would be with “Dark Matter: a century of speculative fiction from the African diaspora,” edited by Sheree R. Thomas, award winning author and current editor of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. The book, published in 2000, is not only the first anthology of science fiction by African American authors but considered by experts as one of the best introductions to the genre.

It includes 25 stories, three novel excerpts and five essays. There are contributions from historical writers like W.E.B. Du Bois (“The Comet,” 1929), well-known authors like Octavia Butler (“The Evening and The Morning and The Night,” 1987) and Samuel R. Delaney (“Aye, and Gomorrah”) and newer writers like Nalo Hopkinson (“Ganger [Ball Lightning]”). Many of the authors will be recognizable to readers, like Walter Mosley, whose “Black to the Future” (1999) is a critical essay on what he believes will be an explosion of Black Science Fiction authors.

Dark Matter is an anthology series of science fiction, fantasy, and horror stories and essays produced by people of African descent. The editor of the series is Sheree Thomas. The first book in the series, Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora (2000), won the 2001 World Fantasy Award for Best Anthology. The second book in the Dark Matter series, Dark Matter: Reading the Bones (2004), won the World Fantasy Award for Best Anthology in 2005. A forthcoming third book in the series is tentatively named Dark Matter: Africa Rising. This was finally published at the end of 2022 under the title Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction, from Tor Books.

In the introduction to the first book, the editor explains that the title alludes to cosmological “dark matter“, an invisible yet essential part of the universe, to highlight how black people’s contributions have been ignored: “They became dark matter, invisible to the naked eye; and yet their influence — their gravitational pull on the world around them — would become undeniable”.

Book I contents

Stories

- Samuel R. Delany, “Aye, and Gomorrah…”

- Octavia E. Butler, “The Evening and the Morning and the Night“

- Charles R. Saunders, “Gimmile’s Songs”

- Steven Barnes, “The Woman in the Wall”

- Tananarive Due, “Like Daughter”

- Jewelle Gomez, “Chicago 1927”

- George S. Schuyler, “Black No More” (excerpt from the novel)

- Ishmael Reed, “Future Christmas” (novel excerpt)

- Kalamu ya Salaam, “Can You Wear My Eyes”

- Robert Fleming, “The Astral Visitor Delta Blues”

- Nalo Hopkinson, “Ganger (Ball Lightning)”

- W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Comet”

- Linda Addison, “Twice, at Once, Separated”

- Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, “Sister Lilith”

- Evie Shockley, “separation anxiety”

- Leone Ross, “Tasting Songs”

- Nalo Hopkinson, “Greedy Choke Puppy”

- Amiri Baraka, “Rhythm Travel”

- Kalamu ya Salaam, “Buddy Bolden”

- Akua Lezli Hope, “The Becoming”

- Charles W. Chesnutt, “The Goophered Grapevine”

- Nisi Shawl, “At the Huts of Ajala”

- Henry Dumas, “Ark of Bones”

- Tony Medina, “Butta’s Backyard Barbecue”

- Kiini Ibura Salaam, “At Life’s Limits”

- Anthony Joseph, “The African Origins of UFOs” (excerpt from the novel)

- Derrick Bell, “The Space Traders“

- Darryl A. Smith, “The Pretended”

- Ama Patterson, “Hussy Strutt”

Essays

- Samuel R. Delany, “Racism and Science Fiction”

- Charles R. Saunders, “Why Blacks Should Read (and Write) Science Fiction”

- Walter Mosley, “Black to the Future”

- Paul D. Miller, a.k.a. DJ Spooky That Subliminal Kid, “Yet Do I Wonder”

- Octavia E. Butler, “The Monophobic Response”

Reviews

- The New York Times Review by Gerald Jonas (2000)

- Scifi.com Review by Joe Monti, Issue 167 (July 2000)

- MAKING BOOKS; Science Fiction, A Black Natural by Martin Arnold, New York Times (2000)

- Steven Silver’s Review

- African American Review by Candice M. Jenkins (Winter 2000)

- Locus Magazine Review by Gary K. Wolfe (July 2000)

- Locus Magazine Review by Faren Miller (June 2000)

- Washington Science Fiction Association (WSFA) Journal Review by Colleen R. Cahill (November 2001)

- Science Fiction Studies at DePauw University Review by Isiah Lavender III (March 2001)

- SF Site Featured Review by Greg L. Johnson (2001)

- A.V. Club Review by Tasha Robinson (2002)

Awards

- 2001 World Fantasy Award for Best Anthology

- 2000 New York Times Notable Book of the Year

- Best SF and Fantasy Books of 2000: Editors’ Choice, Honourable Mention

Book II contents

Stories

- Ihsan Bracy, “ibo landing”

- Cherene Sherrard, “The Quality of Sand”

- Charles R. Saunders, “Yahimba’s Choice”

- Nalo Hopkinson, “The Glass Bottle Trick”

- Kiini Ibura Salaam, “Desire”

- David Findlay, “Recovery from a Fall”

- Douglas Kearney, “Anansi Meets Peter Parker at the Taco Bell on Lexington”

- Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu, “The Magical Negro”

- W. E. B. Du Bois, “Jesus Christ in Texas”

- Henry Dumas, “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?”

- Kevin Brockenbrough, “‘Cause Harlem Needs Heroes”

- Pam Noles, “Whipping Boy”

- Ibi Aanu Zoboi, “Old Flesh Song”

- Walter Mosley, “Whispers in the Dark”

- Tananarive Due, “Aftermoon”

- Tyehimba Jess, “Voodoo Vincent and the Astrostoriograms”

- John S. Cooley, “The Binary”

- Jill Robinson, “BLACKout”

- Charles Johnson, “Sweet Dreams”

- Wanda Coleman, “Buying Primo Time”

- Samuel R. Delany, “Corona”

- Nisi Shawl, “Maggies”

- Andrea Hairston, “Mindscape” (novel excerpt)

- Kalamu ya Salaam, “Trance”

Essays

- Jewelle Gomez, “The Second Law of Thermodynamics”

- Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu, “Her Pen Could Fly: Remembering Virginia Hamilton”

- Carol Cooper, “Celebrating the Alien: The Politics of Race and Species in the Juveniles of Andre Norton”

Reviews

- Locus Magazine Review by Gary K. Wolfe (November 2003)

- Locus Magazine Review by Faren Miller (December 2003)

- SF Site Featured Review by Steven H Silver (2004)

- Scifi.com Review by Pamela Sargent, Issue 354 (2004)

- ChickenBones Literary Journal Review

- BookLoons Review by Martina Bexte (2004)

- Curled Up With a Good Book Review by Brian Charles Clark (2004)

- Austin Chronicle Review by Belinda Acosta (2005)

Awards

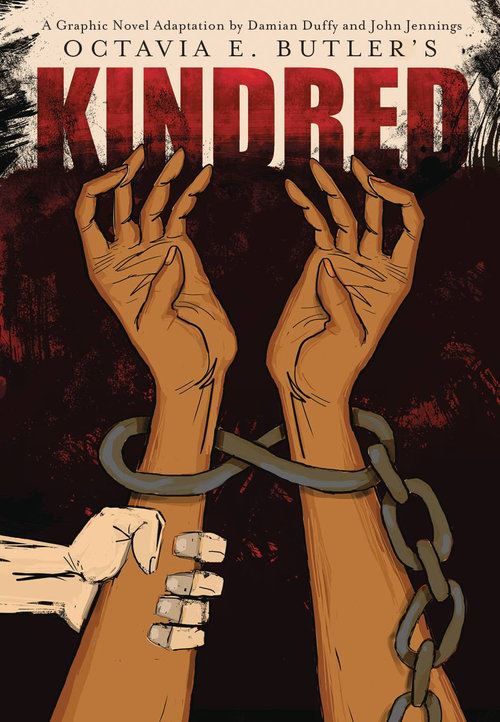

7) KINDRED by OCTAVIA .E. BUTLER

This classic 1979 novel, follows Dana as she travels back and forth between the present day and the Antebellum South. Butler effortlessly parallels the racial tensions of the past and the present day, as the characters explores, first hand, the history of slavery in the United States. She discovers more about herself and her family history in the process. KINDRED is Butler’s seminal work, but really you should try getting more of her books.

Kindred (1979) is a novel by American writer Octavia E. Butler that incorporates time travel and is modeled on slave narratives. Widely popular, it has frequently been chosen as a text by community-wide reading programs and book organizations, and for high school and college courses.

The book is the first-person account of a young African-American writer, Dana, who is repeatedly transported in time between her Los Angeles, California home in 1976 with her white husband and an early 19th-century Maryland plantation just outside Easton. There she meets some of her ancestors: a proud, free Black woman and a white planter who forces her into slavery and concubinage. As Dana stays for longer periods in the past, she becomes intimately entangled with the plantation community. Dana makes hard choices to survive slavery and to ensure her return to her own time.

Kindred explores the dynamics and dilemmas of antebellum slavery from the sensibility of a late 20th-century Black woman, who is aware of its legacy in contemporary American society. Through the two interracial couples who form the emotional core of the story, the novel also explores the intersection of power, gender, and race issues, and speculates on the prospects of future egalitarianism.

While most of Butler’s work is classified as science fiction, Kindred crosses genre boundaries and is also classified as African-American literature. Butler categorized the work as “a kind of grim fantasy.”

Kindred scholars have noted that the novel’s chapter headings suggest something “elemental, apocalyptic, archetypal about the events in the narrative”, thus giving the impression that the main characters are participating in matters greater than their personal lives.

Dana, a young black woman, wakes up in the hospital with her arm amputated. Police deputies question her about the circumstances and ask her whether her husband Kevin, a white man, beats her. Dana tells them that she lost her arm because of an accident and that Kevin is not to blame. When Kevin visits her, they acknowledge being afraid to tell the truth because no one would believe them.

The River

Their lives were altered on June 9, 1976, the day of Dana’s twenty-sixth birthday, in the year the United States was celebrating its bicentennial. The day before, Dana and Kevin had moved into a house a few miles away from their old apartment in Los Angeles. While unpacking, Dana suddenly became dizzy.

When she comes to her senses, she is at the edge of a wood, near a river where a small, red-haired boy is drowning. Dana wades in after him, drags him to shore, and tries to revive him. The boy’s mother begins screaming and hitting Dana, accusing her of killing her son, whom she identifies as Rufus. The boy recovers and a white man arrives and points a gun at Dana, terrifying her. She becomes dizzy again and regains consciousness at her new house with Kevin beside her. Kevin, shocked at her disappearance and reappearance, tries to understand if the episode was real or a hallucination.

The Fire

Dana washes off the filth from the river but dizziness marks another transition. This time, she comes to in a bedroom where a red-haired boy has set his bedroom drapes aflame. He is Rufus, now a few years older. Dana quickly puts out the fire. Rufus confesses he set fire to the drapes to get back at his father for beating him after he stole a dollar. As they talk, Rufus casually uses the N-word to refer to Dana, which upsets her, but she comes to realize that she has been transported in time as well as space, specifically to Maryland, circa 1815.

Rufus advises her to seek refuge at the home of Alice Greenwood and her mother, free blacks who live at the edge of the plantation. Dana realizes that both Rufus and Alice are her ancestors, as they will have a child from whom she will descend. At the Greenwoods’, Dana witnesses a group of young white men smash down the door, drag out Alice’s enslaved father, and whip him brutally for being there without papers. One of the men punches Alice’s mother when she refuses his advances. The men leave, Dana comes out of hiding, and helps Alice’s mother. She is confronted by one of the white men, who attempts to rape her. Fearing for her life, Dana luckily returns to 1976.

Though hours have passed for her, Kevin assures her that she has been gone only for a few minutes. The next day, Kevin and Dana prepare for the possibility that she may travel back in time again by packing a survival bag for her and by doing some research on Black history in books in their home library.

The Fall

In a flashback, Dana recounts how she met Kevin while doing minimum-wage temporary jobs at an auto-parts warehouse. Kevin becomes interested in Dana when he learns she is a writer and they become friends, although co-workers are judgmental because he is white. The two find they have much in common; both are orphans, both love to write, and both their families disapproved of their aspiration to become writers. They become lovers.

Again in 1976, Kevin is preparing to go to the library to find out how to forge “free papers” for Dana. She feels dizzy and Kevin holds her, traveling with her to the past. They find Rufus writhing in pain from a broken leg. Next to him is a black boy named Nigel, whom they send to the main house for help.

Rufus reacts with violent disbelief when he finds out that Kevin and Dana are married: whites and blacks are not allowed to marry in his time, although he knows many white men have enslaved black mistresses. Dana and Kevin explain to Rufus that they are from the future and prove it by showing the dates stamped on the coins Kevin carries in his pockets. Rufus promises to keep their identities a secret, and Dana tells Kevin to pretend that he is her owner. When Tom Weylin, Rufus’s father, arrives with his slave Luke to retrieve Rufus, Kevin introduces himself. Weylin grudgingly invites him to dinner.

At the Weylin plantation, Rufus’s mother Margaret fusses about her son’s well-being and, jealous of the attention Rufus shows Dana, sends the young woman to the cookhouse. There, Dana meets two house slaves: Sarah, the cook; and Carrie, her mute daughter. Unsure as to what their next act should be, Kevin accepts Weylin’s offer to become Rufus’s tutor. Kevin and Dana stay on the plantation for several weeks. They observe the relentless cruelty and torture that Weylin, Margaret, and the spoiled Rufus use against the slaves. They are sadistic and evil, they feel entitled to treat the slaves as property. Weylin catches Dana teaching Nigel, a slave boy, how to read and whips her mercilessly. The dizziness overcomes her before Kevin can reach her, she travels back to 1976 alone.

The Fight

In a flashback, Dana remembers how she and Kevin were married. Both of their families opposed the marriage due to ethnic bias. While Kevin’s reactionary sister is prejudiced against African Americans, Dana’s uncle abhors the idea of a white man eventually inheriting his property. Only Dana’s aunt favors the union, as it would mean that her niece’s children would have lighter skin. Kevin and Dana marry without any family present.

After eight days of being home recuperating without Kevin, Dana time travels to find Rufus getting beaten up by Isaac Jackson, the enslaved husband of Alice Greenwood. Dana learns that Rufus had attempted to rape Alice, who was once his childhood friend. Dana convinces Isaac not to kill Rufus, and Alice and Isaac run away while Dana gets Rufus home. She learns that it has been five years since her last visit and that Kevin has left Maryland. Dana nurses Rufus back to health in return for his help delivering letters to Kevin. Five days later, Alice and Isaac are caught.

Isaac is mutilated and sold to traders heading to Mississippi. Alice is beaten, savaged by dogs, and enslaved as penalty for helping Isaac escape. Rufus, who claims to love Alice, buys her, and orders Dana to nurse her back to health. Dana does so with much care. When Alice finally recovers, she curses Dana for not letting her die, and is wracked with grief for her lost husband.

Rufus orders Dana to convince Alice to have sex with him now that she has recovered. Dana speaks with Alice, outlining her three options: she can refuse and be whipped and raped; she can acquiesce; or she can try again to run away. Injured and terrified by her previous punishment, Alice gives in to Rufus’s desire and becomes his concubine. While in his bedroom, Alice learns that Rufus did not send Dana’s letters to Kevin, and tells Dana. Furious that Rufus lied to her, Dana runs away to find Kevin, but is betrayed by a jealous slave, Liza. Rufus and Weylin capture her and Weylin whips her brutally.

When Weylin learns that Rufus failed to keep his promise to Dana to send her letters, he writes to Kevin and tells him that Dana is on the plantation. Kevin comes to retrieve Dana, but Rufus stops them on the road and threatens to shoot them. He tells Dana that she can’t leave him again. The dizziness overcomes Dana and she travels back to 1976, this time with Kevin.

The Storm

Dana’s and Kevin’s happy reunion is short-lived, as Kevin has a hard time adjusting to the present after living in the past for five years. He shares a few details of his life in the past with Dana: he witnessed terrible atrocities against slaves, traveled farther up north, worked as a teacher, helped slaves escape, and grew a beard to disguise himself from a lynch mob. Disconcerted about his trouble in re-entering his former world, he grows angry and cold. Deciding to let him work his feelings out, Dana packs a bag in case she time travels again.

Soon enough she finds herself outside the Weylin plantation house in a rainstorm, with a very drunk Rufus lying face down in a puddle. She tries to drag him back to the house, then gets Nigel to help her carry him. At the house, an aged Weylin appoints Dana to nurse Rufus back to health under threat of her life. Suspecting Rufus has malaria and knowing she cannot help much, Dana feeds Rufus the aspirin she has packed to lower his fever. Rufus survives, but remains weak for weeks. Dana learns that Rufus and Alice have had three mixed-race “children of the plantation“ and that only one, a boy named Joe, has survived. Alice is pregnant again. Rufus had forced Alice to let the doctor bleed the other two when they had fallen ill, a customary treatment of the time, but it killed them.

Weylin has a heart attack and Dana is unable to save his life. But, Rufus believes she let Weylin die and sends her to work in the corn fields as punishment. By the time he repents his decision, she has collapsed from exhaustion and is being whipped by the overseer. Rufus appoints Dana as the caretaker of his ailing mother, Margaret. Now the master of the plantation, Rufus sells off some slaves, including Tess, Weylin’s former concubine. Dana expresses her anger about that sale, and Rufus explains that his father left debts he must pay. He convinces Dana to use her writing skill to stave off his other creditors.

Time passes and Alice gives birth to a girl, Hagar, a direct ancestor of Dana. Alice confides that she plans to run away with her children as soon as possible, as she fears that she is forgetting to hate Rufus. Dana convinces Rufus to let her teach his son Joe and some of the slave children how to read. However, when a slave named Sam asks Dana if his younger siblings can join in on the lessons, Rufus sells him off as punishment for flirting with her. When Dana tries to interfere, Rufus hits her. Faced with her own powerlessness over Rufus, she retrieves the knife she has brought from home and slits her wrists in an effort to time travel.

The Rope

Dana awakens in Los Angeles, at home, with her wrists bandaged and Kevin by her side. She tells him of her eight months in the plantation, of Hagar’s birth, and of the need to keep Rufus alive, as the slaves would be separated and sold if he died. When Kevin asks if Rufus has raped Dana, she responds that he has not, that such an attempt would cause her to kill him, despite the possible consequences.

Fifteen days later, on the 4th of July, Dana returns to the plantation. There she finds that Alice has hanged herself. Alice tried to run away after Dana disappeared, and as punishment Rufus whipped her and told her that he had sold her children when he had actually sent to them to stay with his aunt in Baltimore. Racked with guilt about Alice’s death, Rufus nearly commits suicide himself.

After Alice’s funeral, Dana uses that guilt to convince Rufus to free his children by Alice. From that moment on, Rufus keeps Dana at his side almost constantly, having her share meals and teach his children. One day, he finally admits that he wants Dana to replace Alice in his life. He says that unlike Alice, who, despite growing used to Rufus, never stopped plotting to escape him, Dana will see that he is a fair master and eventually stop hating him. Dana, horrified at the thought of forgiving Rufus in this way, flees to the attic to find her knife. Rufus follows her there, and when he attempts to rape her, Dana stabs him twice with her knife. Nigel arrives to see Rufus’s death throes, at which point Dana becomes terribly sick and time travels home for the last time. She finds herself in excruciating pain, as her arm has been joined to a wall in the spot where Rufus was holding it.

Dana and Kevin travel to Baltimore to investigate the fate of the Weylin plantation after Rufus’s death in archival records, but they find very little: a newspaper notice reporting Rufus’s death as a result of his house catching fire, and a Slave Sale announcement listing all the Weylin slaves except Nigel, Carrie, Joe, and Hagar. Dana speculates that Nigel covered up the murder by starting the fire, and feels responsible for the sale of the slaves. To that, Kevin responds that she cannot do anything about the past, and now that Rufus is finally dead, they can return to their peaceful life together.

Television

In March 2021, it was announced that FX had given the production a pilot order for a television adaptation of the novel. In January 2022, it was announced that FX had given the production a series order for a first season consisting of 8 episodes, starring Mallori Johnson as Dana, Micah Stock as Kevin, Ryan Kwanten as Tom Weylin, Gayle Rankin as Margaret Weylin, Austin Smith as Luke, Sophina Brown as Sarah, and David Alexander Kaplan as Rufus Weylin. It is produced by FX Productions, with Branden Jacobs-Jenkins as showrunner. The series premiered all 8 episodes on December 13, 2022, on Hulu. The episodes of season one cover the first three chapters of the novel, The River, The Fire, and The Fall, though some major changes from the novel have been made for the series, including setting the current day in 2016 rather than 1976, having Dana and Kevin not married but in a new relationship, and adding Dana’s mother Olivia as a new character who also travels through time. In January 2023, it was reported that the series had been canceled after one season.

Characters

- Edana (Dana) Franklin: A 26-year-old African-American woman writer, she is the protagonist and the narrator of the story. She is married to a white writer named Kevin. She repeatedly travels in time to a slave plantation in antebellum Maryland, where she first encounters a white ancestor as the boy Rufus. There Dana has to make hard compromises to survive and to ensure her life in her own time.

- Kevin Franklin: Dana’s husband is a white writer twelve years older than she. Kevin loves her deeply and became estranged from his family to marry her. When he travels with Dana to the past, he witnesses the brutality of slavery and becomes an abolitionist, also helping slaves escape to freedom.

- Rufus Weylin: The red-haired son of white planter Tom Weylin and his wife; the father owns a Maryland plantation and numerous slaves. As Dana returns, she sees the adult Rufus replace his father as master. Rufus rapes Alice, a free black woman, and their mixed-race daughter Hagar later becomes one of Dana’s maternal ancestors.

- Tom Weylin: The owner of an antebellum Maryland plantation, he is a hard master and father, insisting on obedience from family and slaves. He whips Dana on multiple occasions, and authorizes the selling of his slaves’ children. He is likened to Kevin in looks.

- Alice Greenwood (later, Alice Jackson): She was born free and is a proud Black woman. Later she is enslaved as punishment for having helped her enslaved husband Isaac try to escape. Rufus buys Alice and forces her to become his concubine. Two of their children survive: Joe and Hagar. She hangs herself after Rufus tells her he has sold her children.

- Sarah: The cook of the Weylin household is its domestic manager; she tries to protect the house slaves while making them work hard. Tom Weylin sold all of Sarah’s children except her mute daughter Carrie.

- Margaret Weylin: The plantation owner’s wife indulges their son Rufus. Both she and her husband are abusive to the house slaves. She leaves after her infant twins die and returns with an opium addiction.

- Hagar Weylin: Rufus and Alice’s youngest daughter. Hagar is a direct ancestor of Dana through her maternal line.

- Luke: A slave at the Weylin plantation who works as Weylin’s overseer. Weylin sells him for not being sufficiently obedient.

- Nigel: The son of Luke and an enslaved woman at the Weylin plantation. He and Rufus were playmates as children. Dana secretly teaches him as a child to read and write. When older, he tries to flee, but is captured. Held at the plantation, he forms a family with Sarah’s daughter, Carrie.

- Carrie: Sarah’s daughter is mute, but she helps Dana find the strength for the hard compromises she must make to survive. She becomes Nigel’s wife.

- Liza: An enslaved woman jealous of Dana for what she thinks is special treatment, she snitches on Dana when she runs away. This results in Dana being caught and whipped.

- Tess: An enslaved woman whom Tom Weylin uses sexually.

- Jake Edwards: One of the white overseers on the Weylin plantation, he also abuses Tess sexually.

Main themes

Realistic depiction of slavery and slave communities

Dana reporting on the slaves’ attitude toward Rufus as slave master: “Strangely, they seemed to like him, hold him in contempt, and fear him all at the same time.”

Kindred, page 229.

Kindred explores how a modern black woman would deal with a slave society, where most black people were considered property; it was a world where “all of society was arrayed against you”. During an interview, Butler said that, while she read slave narratives for background, she believed that if she wanted people to read her book, she would have to present a less violent version of slavery than found in these accounts.

Scholars of Kindred consider the novel an accurate, fictional account of many slave lives. Concluding that “there probably is no more vivid depiction of life on an Eastern Shore plantation than that found in Kindred”, Sandra Y. Govan traces how Butler’s book follows the classic patterns of the slave narrative genre: loss of innocence, harsh punishment, strategies of resistance, life in the slave quarters, struggle for education, experience of sexual abuse, realization of white religious hypocrisy, and attempts to escape, with ultimate success.

Robert Crossley notes that Butler’s intense first-person narration deliberately echoes many slave narratives, thereby giving the story “a degree of authenticity and seriousness”. Lisa Yaszek sees Dana’s visceral first-hand account as a deliberate criticism of earlier depictions of slavery, such as the book and film Gone with the Wind, produced largely by whites, and even the television miniseries Roots, based on a book by African-American writer Alex Haley.

In Kindred, Butler portrays individual slaves as distinctive persons, giving each his or her own story. Robert Crossley says that Butler treats the blackness of her characters as “a matter of course”, to resist the tendency of white writers to incorporate African Americans into their narratives just to illustrate a problem or to divorce themselves from charges of racism. Thus, in Kindred the slave community is depicted as a “rich human society”: the proud yet victimized freewoman Alice; Sam the field slave, who hopes Dana will teach his brother to read and write; Liza, who frustrates Dana’s escape; the bright and resourceful Nigel, Rufus’s childhood friend who learns to read from a stolen primer; and, most importantly, Sarah the cook, who Butler develops as a deeply angry yet caring woman subdued only by the threat of losing her last child, the mute Carrie.

Master-slave power dynamics

Rufus expressing his “destructive single-minded love” for Alice in a conversation with Dana:

“I begged her not to go with him,” he said quietly. “Do you hear me, I begged her!”

I said nothing. I was beginning to realize that he loved the woman—to her misfortune. There was no shame in raping a black woman, but there could be shame in loving one.

“I didn’t want to just drag her off into the bushes,” said Rufus. “I never wanted it to be like that. But she kept saying no. I could have had her in the bushes years ago if that was all I wanted.” … “If I lived in your time, I would have married her. Or tried to.”

Kindred, page 124.

Scholars have argued that Kindred complicates a common representations of chattel slavery as an oppressive system dominated by the master and economic goals. Pamela Bedore notes that while Rufus seems to hold all the power in relationship to Alice, she never wholly surrenders to him. Alice’s suicide can be read as her “final upsetting of their power balance”, and escaping him through death. By placing Kindred in comparison to other Butler novels such as Dawn, Bedore explores the bond between Dana and Rufus as re-envisioning slavery as a “symbiotic” interaction between slave and master: since neither character can exist without the other, they are continually forced to collaborate in order to survive. The master does not simply control the slave but depends on her. From the side of the slave, Lisa Yaszek notices conflicting emotions: in addition to fear and contempt, affection may be felt for the familiar whites and their occasional kindnesses. A slave who collaborates with the master to survive is not reduced to a “traitor to her race” or to a “victim of fate.”

Kindred portrays the exploitation of black female sexuality as a main site of the historic struggle between master and slave. Diana Paulin describes Rufus’s attempts to control Alice’s sexuality as a means to recapture power he lost when she chose Isaac as her sexual partner. Compelled to submit sexually to Rufus, Alice divorces her desire to preserve a sense of self. Similarly, Dana reconstructs her sexuality while time traveling to survive. While in the present, Dana chooses her husband and enjoys sex with him. In the past, her status as a black female forced her to submit to the master as sexual property. Rufus as an adult attempts to control Dana’s sexuality, and attempts rape to use her to replace Alice. Dana’s killing Rufus is the way she rejects the role of female slave, distinguishing herself from those who did not have the power to say “no.”

Critique of American history

Dana obeying Rufus’ instructions to burn her paperback on the history of slavery in America:

“The fire flared up and swallowed the dry paper, and I found my thoughts shifting to Nazi book burnings. Repressive societies always seemed to understand the danger of ‘wrong’ ideas.”

Kindred, page 141.

Scholarship on Kindred often touches on its critique of the official history of the formation of the United States as an erasure of the raw facts of slavery. Lisa Yaszek places Kindred as emanating from two decades of heated discussion over what constituted American history, with a series of scholars pursuing the study of African-American historical sources to create “more inclusive models of memory.” Missy Dehn Kubitschek argues that Butler set the story during the bicentennial of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence of the United States to suggest that the nation should review its history in order to resolve its current racial strife. Robert Crossley believes that Butler dates Dana’s final trip to her Los Angeles home on the Bicentennial to connect the personal with the social and the political. The power of this national holiday to erase the grim reality of slavery is negated by Dana’s living understanding of American history, which makes all her previous knowledge of slavery through mass media and books inadequate. Yaszek further notes that Dana throws away all her history books about African-American history on one of the trips back to her California home, as she finds them to be inaccurate in portraying slavery. Instead, Dana reads books about the Holocaust and finds these books to be closer to her ordeals as a slave.

In several interviews, Butler mentioned that she wrote Kindred to counteract stereotypical conceptions of the submissiveness of slaves. While studying at Pasadena City College, Butler had heard a young man from the Black Power Movement express his contempt for older generations of African Americans for what he considered their shameful submission to white power. Butler realized the young man did not have enough context to understand the necessity to accept abuse just to keep oneself and one’s family alive and well. Thus, Butler resolved to create a modern African-American character, who would go back in time to see how well he (Butler’s protagonist was originally male) could withstand the abuses his ancestors had suffered.

As Ashraf A. Rushdy explains, Dana’s memories of her enslavement become a record of the “unwritten history” of African Americans, a “recovery of a coherent story explaining Dana’s various losses.” By living these memories, Dana makes connections between slavery and contemporary late 20th century social situations, including the exploitation of blue-collar workers, police violence, rape, domestic abuse, and racial segregation.

Trauma and its connection to historical memory (or historical amnesia)

Kindred reveals the repressed trauma that slavery caused in the United States’ collective historical memory. In an interview in 1985, Butler suggested that this trauma comes partly from attempts to forget America’s dark past: “I think most people don’t know or don’t realize that at least 10 million blacks were killed just on the way to this country, just during the middle passage….They don’t really want to hear it partly because it makes whites feel guilty.” In a later interview with Randall Kenan, Butler explained how debilitating this trauma has been, as she symbolized by having her protagonist lose her left arm.

She said:

“I couldn’t really let [Dana] come all the way back. I couldn’t let her return to what she was, I couldn’t let her come back whole and [losing her arm], I think, really symbolizes her not coming back whole. Antebellum slavery didn’t leave people quite whole.”

Many academics have extended Dana’s loss as a metaphor for the “lasting damage of slavery on the African American psyche” to include other meanings. For example, Pamela Bedore interprets it as the loss of Dana’s naïveté regarding the supposed progress of racial relations in the present. For Ashraf Rushdy, Dana’s missing arm is the price she must pay for her attempt to change history. Robert Crossley quotes Ruth Salvaggio as inferring that the amputation of Dana’s left arm is a distinct “birthmark” that represents a part of a “disfigured heritage.” Scholars have also noted the importance of Kevin having his forehead scarred during his travel to the past. Diana R. Paulin argues that it symbolizes Kevin’s changing understanding of racial realities, which constitute “a painful and intellectual experience”.

Race as social construct

Kevin and Dana differing in their perspectives of the 19th Century:

“This could be a great time to live in,” Kevin said once. “I keep thinking what an experience it would be to stay in it— go West and watch the building of the country, see how much of the Old West mythology is true.”

“West,” I said bitterly. “That’s where they’re doing it to the Indians instead of the blacks!”

He looked at me strangely. He had been doing that a lot lately.”

Kindred, page 97.

The construction of the concept of “race” and its connections to slavery are central themes in Butler’s novel. Mark Bould and Sherryl Vint place Kindred as a key science fiction literary text of the 1960s and 1970s black consciousness period, noting that Butler uses the time travel trope to underscore the perpetuation of past racial discrimination into the present and, perhaps, the future of America. The lesson of Dana’s trips to the past, then, is that “we cannot escape or repress our racist history but instead must confront it and thereby reduce its power to pull us back, unthinkingly, to earlier modes of consciousness and interaction.”

The novel’s focus on how the system of slavery shapes its central characters dramatizes society’s power to construct raced identities. The reader witnesses the development of Rufus from a relatively decent boy allied to Dana to a “complete racist” who attempts to rape her as an adult. Similarly, Dana and Kevin’s prolonged stay in the past reframes their modern attitudes. Butler’s depiction of her principal character as an independent, self-possessed, educated African-American woman defies slavery’s racist and sexist objectification of black people and women.

Kindred also challenges the fixity of “race” through the interracial relationships that form its emotional core. Dana’s kinship to Rufus disproves America’s erroneous concepts of racial purity. It also represents the “inseparability” of whites and blacks in America. The negative reactions of characters in the past and the present to Dana and Kevin’s interracial relationship highlight the continuing hostility of both white and black communities to interracial mixing. At the same time, the relationship of Dana and Kevin extends the concept of “community” from people related by ethnicity to people related by shared experience. In these new communities, whites and black people may acknowledge their common racist past and learn to live together.

The depiction of Dana’s white husband, Kevin, also serves to examine the concept of racial and gender privilege. In the present, Kevin seems unconscious of the benefits he derives from his skin color, as well as of the way his actions serve to disenfranchise Dana. Once he goes to the past, however, he must not just resist accepting slavery as the normal state of affairs, but dissociate himself from the unrestricted power white males enjoy as their privilege. His prolonged stay in the past transforms him from a naive white man oblivious about racial issues into an anti-slave activist fighting racial oppression.

The meaning of the novel’s title: blood relations and interracial marriage

Kindred’s title has several meanings: at its most literal, it refers to the genealogical link between its modern-day protagonist, the slave-holding Weylins, and both the free and bonded Greenwoods; at its most universal, it points to the kinship of all Americans regardless of ethnic background.

Since Butler’s novel challenges readers to come to terms with slavery and its legacy, one significant meaning of the term “kindred” is the United States’ history of miscegenation and its denial by official discourses. The literal kinship of black people and whites must be acknowledged if America is to move into a better future.

On the other hand, as Ashraf H. A. Rushdy contends, Dana’s journey to the past serves to redefine her concept of kinship from blood ties to that of “spiritual kinship” with those she chooses as her family: the Weylin slaves and her white husband, Kevin. This sense of the term “kindred” as a community of choice is clear from Butler’s first use of the word to indicate Dana and Kevin’s similar interests and shared beliefs. Dana and Kevin’s relationship, in particular, may signal the way for black and white America to reconcile: they must face the country’s racist past together so they can learn to co-exist as kindred.

As Farah Peterson discusses in “Alone with Kindred”, the novel stands out as one of the only works of 20th-century American literature to centre an interracial couple as protagonists and explore interracial marriage as one of its main themes.

Strong female protagonist

Dana explains to Kevin that she will not allow Rufus to turn her into property:

“I am not a horse or a sack of wheat. If I have to seem to be property, if I have to accept limits on my freedom for Rufus’s sake, then he also has to accept limits – on his behavior towards me. He has to leave me enough control of my own life to make living look better to me than killing and dying.”

Kindred, page 246.

In her article “Feminisms”, Jane Donawerth describes Kindred as a product of more than two decades of recovery of women’s history and literature that began in the 1970s. The republication of a significant number of slave narratives, as well as the work of Angela Davis, who highlighted the heroic resistance of the black female slave, introduced science fiction writers such as Octavia Butler and Suzy McKee Charnas to a literary form that redefined the heroism of the protagonist as endurance, survival, and escape. As Lisa Yaszek notes further, many of these African-American woman’s neo-slave narratives, including Kindred, discard the lone male hero in favor of a female hero immersed in family and community. Robert Crossley sees Butler’s novel as an extension of the slave women’s memoirs exemplified by texts such as Harriet Ann Jacobs‘ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, especially in its portrayal of the compromises the heroine must make, the endurance she must have, and her ultimate resistance to victimization.

Originally, Butler intended for the protagonist of Kindred to be a man, but as she explained in her interview, she could not do so because a man would immediately be “perceived as dangerous”: “[s]o many things that he did would have been likely to get him killed. He wouldn’t even have time to learn the rules…of submission.” She realized that sexism could aid a female protagonist, “who might be equally dangerous” but “would not be perceived so.”

Most scholars see Dana as an example of a strong female protagonist. Angelyn Mitchell describes Dana as a black woman “strengthened by her racial pride, her personal responsibility, her free will, and her self-determination.” Identifying Dana as one of Butler’s many strong female black heroes, Grace McEntee explains how Dana attempts to transform Rufus into a caring individual despite her struggles with a white patriarchy. These struggles, Missy Dehn Kubitschek explains, are clearly represented by Dana’s resistance to white male control of a crucial aspect of her identity—her writing—both in the past and in the present. Sherryl Vint argues that, by refusing to have Dana be reduced to a raped body, Butler would seem to be aligning her protagonist with “the sentimental heroines who would rather die than submit to rape” and thus “allows Dana to avoid a crucial aspect of the reality of female enslavement.” However, by risking death by killing Rufus, Dana becomes a permanent surviving record of the mutilation of her black ancestors, both through her one-armed body and by becoming “the body who writes Kindred.” In contrast to these views, Beverly Friend believes Dana represents the helplessness of modern woman and that Kindred demonstrates that women have been and continue to be victims in a world run by men.

Female quest for emancipation

After briefly considering giving in to Rufus’ sexual advances, Dana steels herself to stab him:

“I could feel the knife in my hand, still slippery with perspiration. A slave was a slave. Anything could be done to her. And Rufus was Rufus— erratic, alternately generous and vicious. I could accept him as my ancestor, my younger brother, my friend, but not as my master, and not as my lover.”

Kindred, page 260.

Some scholars consider Kindred as part of Butler’s larger project to empower black women. Robert Crossley sees Butler’ science fiction narratives as generating a “black feminist aesthetic” that speaks not only to the socio-political “truths” of the African-American experience, but specifically to the female experience, as Butler focuses on “women who lack power and suffer abuse but are committed to claiming power over their own lives and to exercising that power harshly when necessary.” Given that Butler makes Dana go from liberty to bondage and back to liberty beginning on the day of her birthday, Angelyn Mitchell views Kindred as a revision of the “female emancipatory narrative” exemplified by Harriet A. Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, with Butler’s story engaging in themes such as female sexuality, individualism, community, motherhood, and, most importantly, freedom in order to illustrate the types of female agency that are capable of resisting enslavement.

Similarly, Missy Dehn Kubistchek reads Butler’s novel as “African-American woman’s quest for understanding history and self” which ends with Dana extending the concept of “kindred” to include both her black and white heritage, as well as her white husband, while “insisting on her right to self definition.”

Genre

Publishers and academics have had a hard time categorizing Kindred. In an interview with Randall Kenan, Butler stated that she considered Kindred “literally” as “fantasy”. According to Pamela Bedore, Butler’s novel is difficult to classify because it includes both elements of the slave narrative and science fiction. Frances Smith Foster insists Kindred does not have one genre and is in fact a blend of “realistic science fiction, grim fantasy, neo-slave narrative, and initiation novel.” Sherryl Vint describes the narrative as a fusion of the fantastical and the real, resulting in a book that is “partly historical novel, partly slave narrative, and partly the story of how a twentieth century black woman comes to terms with slavery as her own and her nation’s past.”

Critics who emphasize Kindred’s exploration of the grim realities of antebellum slavery tend to classify it mainly as a neo-slave narrative. Jane Donawerth traces Butler’s novel to the recovery of slave narratives during the 1960s, a form then adapted by female science fiction writers to their own fantastical worlds. Robert Crossley identifies Kindred as “a distinctive contribution to the genre of neo-slave narrative” and places it along Margaret Walker‘s Jubilee, David Bradley‘s The Chaneysville Incident, Sherley Anne Williams‘s Dessa Rose, Toni Morrison‘s Beloved, and Charles R. Johnson‘s Middle Passage. Sandra Y. Govan calls the novel “a significant departure” from the science fiction narrative not only because it is connected to “anthropology and history via the historical novel”, but also because it links “directly to the black American slave experiences via the neo-slave narrative.” Noting that Dana begins the story as a free black woman who becomes enslaved, Marc Steinberg labels Kindred an “inverse slave narrative.”

Still, other scholars insist that Butler’s background in science fiction is key to our understanding of what type of narrative Kindred is. Dana’s time traveling, in particular, has caused critics to place Kindred along science fiction narratives that question “the nature of historical reality,” such as Kurt Vonnegut‘s “time-slip” novel Slaughterhouse Five and Philip K. Dick‘s The Man in the High Castle, or that warn against “negotiat[ing] the past through a single frame of reference,” as in William Gibson’s “The Gernsback Continuum.” In her article “A Grim Fantasy”, Lisa Yaszek argues that Butler adapts two tropes of science fiction—time-travel and the encounter with the alien Other—to “re-present African-American women’s histories.” Raffaella Baccolini further identifies Dana’s time traveling as a modification of the “grandfather paradox” and notices Butler’s use of another typical science fiction element: the narrative’s lack of correlation between time passing in the past and time passing in the present.

Style