Okonkwo is in conversation with Gbenga Adesina, a Nigerian poet and essayist. He received his MFA from New York University where he held the Goldwater Poetry Fellowship and was mentored by Yusef Komunyakaa. He has received support from the Poet’s House, New York, Fine Arts Work Center, Provincetown, Colgate University’s Olive B. O’Connor Fellowship, Folger Shakespeare’s Library, Washington DC, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Harlem, and Harvard University’s historic Woodberry Poetry Room. His work has been published in the Paris Review, Harvard Review, Academy of American Poets’ Poem-A-Day, Guernica, Yale Review, New York Times Magazine, and elsewhere, and has been translated into multiple languages. He’s the inaugural Mellon Foundation Post-doctoral Fellow in Global Black and Diasporic Poetry at the Furious Flower Poetry Center, James Madison University.

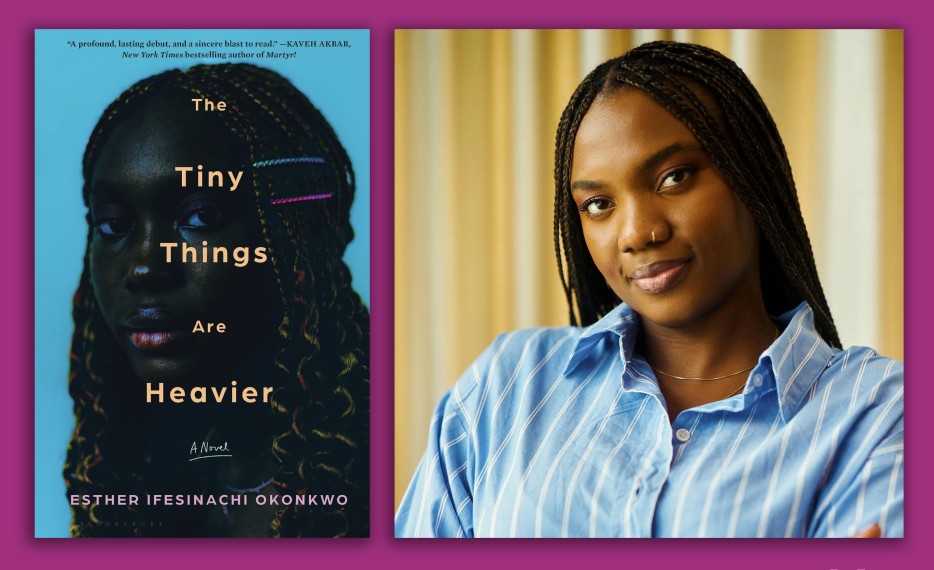

When Nigerian writer Esther Ifesinachi Okonkwo first arrived in America to further her education, she was 23 and a fog sat at the edge of her mind. It was a kind of fog characterized by inexperience, and the acute awareness of that inexperience. “I was trying to figure out who I was. I felt that there was something that I should know that I did not know and that frustrated me a lot,” She says, “There were so many things that were so unclear to me, and then they began to unwrap themselves slowly.”

It is from this feeling of existential cluelessness that she created the emotional composition of Somkelechukwu, the main character in The Tiny Things Are Heavier, her stunning debut novel about a Nigerian immigrant woman and her convoluted journey towards self-discovery.

When we first met Somkelechukwu, who is affectionately referred to as Sommy in the book, she is entering a new country and a new life. In her early twenties, Sommy is at once in awe of everything in this new world and also seriously disoriented by the life that has thrust her into.

‘The Things Are Heavier’ is a stirring and masterfully delivered bildungsroman that followed a young Nigerian woman as she tries to make sense of her new life and what exactly she wants from it.

The book, which will resonates with fans of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah and Nicole Dennis-Benn’s Patsy, follows Sommy’s journey as she navigates life as a graduate student, studying a course she has little interests in, but that provides an anchor away from a life she has been told she must stay away from. The story takes place between Lagos and Iowa, touching on themes of grief, listless essential, belonging and Identity.

In Tiny Things, Okonkwo writes with impeccable observations of the quirks that defines human nature. Nothing escapes her sharp gaze, from the way a character perceives the smell in her space to the way monumental events disrupt their self-perception.

Okonkwo’s writing is often taut and skillfully restrained, even when dissecting a seemingly minor detail for long paragraphs. Her ability to transform small complications into compelling philosophical arguments is masterfully impressive. It’s what makes this book Wise and Thoughtful. Also present is Okonkwo’s understanding of how national tragedies impact the lives of young Nigerians.

“The book started to form for me during the #ENDSARS movement,” Okonkwo explains. “I then began to think about the ways that these sort of big structures can shape your life, can shape the way you love, can shape the way you interact with people, and can even shape the chemicals stimulated in your brain,”.

Okonkwo’s work joins a list of many art pieces that have been born from the #ENDSARS protests that claimed the life’s of many Nigerians who were shot at by Military officers. What Okonkwo does in her debut is settle on the disappointment and sense if despair that comes from living in a country without systems, a country that has it’s arms on your back, pushing you to run as far as you can.

A ‘Coming/Turning’ of Age

On the face of it, “The Tiny Things Are Heavier” could be described as a story of migration. It does feature lot of movements and the feelings of displacements that comes with it. A closer look, however, will reveal that migration function here as a feature, rather than the hearts of the story. More pressing are issues of human character: how do we perceive ourselves and our capacity to be good or bad, the book asks. Who are we when Cultural expectations no longer shape our identity?

Sommy’s ability to have her legs between two worlds shifts her sense of privilege and sense of self. While in the United States, she is forced to grapple more with why she chose to leave and who she has become as a result of that, and back home, she is faced with the guilt of one who has found a way out. With steady emotional agility, the book shifts between Sommy’s complicated relationships with her partner, Bryan, with whom she shares a life-altering connection, and her non-existent relationship with herself.

It’s what’s makes this book a skillfully crafted bildungsroman. “I just didn’t want this to be a migrant novel,” Okonkwo explains. “I wanted it to be a person trying to move from young adulthood to maturity.” Throughoutthebook, Sommy’s faces varying emotional and situational challenges in a way that upsets traditional Categorizations of good and bad behavior. In this book, Okonkwo says she aimed to dissect not the categorization of behavior but it’s ability to exist outside the binary. “I wanted her to go through all that is required to get an understanding of yourself.”

Okonkwo’s works arrives at a delicate time in both the US and Nigerian politics. Like many of the characters in this book, there’s restlessness among young Nigerians that is drawing their gaze away from their own homes. And in the US stricter immigration policies are bringing up questions of who gets to have a better life and at what cost?

By making the characters exhibit both Unkindness and care towards each other. Okonkwo highlights that special ability of humans to love with contradictions.

“I want people to lean into the ugliness of being human. I think we are so preoccupied with the purity in a world that is so Impure,” Okonkwo says. “Look at the world a look at the things that are happening on the world and the decisions that people are making. They don’t come from one big evil act. These are little tiny choices that people make that then lead to all of this sort of destruction that we see. And I think that there’s a tendency for all of is to shy away from those small evils.”

Before writing this book, Okonkwo had pieces published in Guernica, VQR, Catapult, and other places. Writing this book was transformative for Okonkwo. Written over the course of four years, Okonkwo who graduated from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and was a recipient of the Elizabeth George Foundation Grant wrote to herself through a difficult time in her life. “I was terribly unhappy,” she says. “I had not seen my family for a long time as I couldn’t afford to travel as much as I’d like. My father was ill at one point and I couldn’t go back to see him. Normal life challenges, but most of them I had to sort out and figure out alone.” It was from those feelings of stress and relentless unbelonging that she infused her characters with depth.

Okonkwo makes a wise choice to tell this story through Sommy’s compelling close third-person point of view, which portrays her as anxious and exasperated, strong-willed and intelligent, cynical and devoted. She loves her home even as she works to escape it. “If life, she thinks, its surprises, the slices of deep joy contained, its ruggedness and impliability, its contradictions, the implosion of it, the nonsense of it, were a physical place, it would be Lagos.” In returning, Sommy feels “the loss of a place for which to pine. She had gone home, and home did not feel like home.” Through Sommy’s experiences in Nigeria and in Iowa, Okonkwo asks her readers to reflect upon class, privilege, race, gender, and their interlocking power structures, as well as the importance of place to one’s sense of self. The Tiny Things Are Heavier is thought-provoking and unforgettable.

At it’s core, Okonkwo hopes that these books speak to the times, but also to the complexity of the human condition. “I want us to be more comfortable with our mistakes, owning them, then working to change them.”