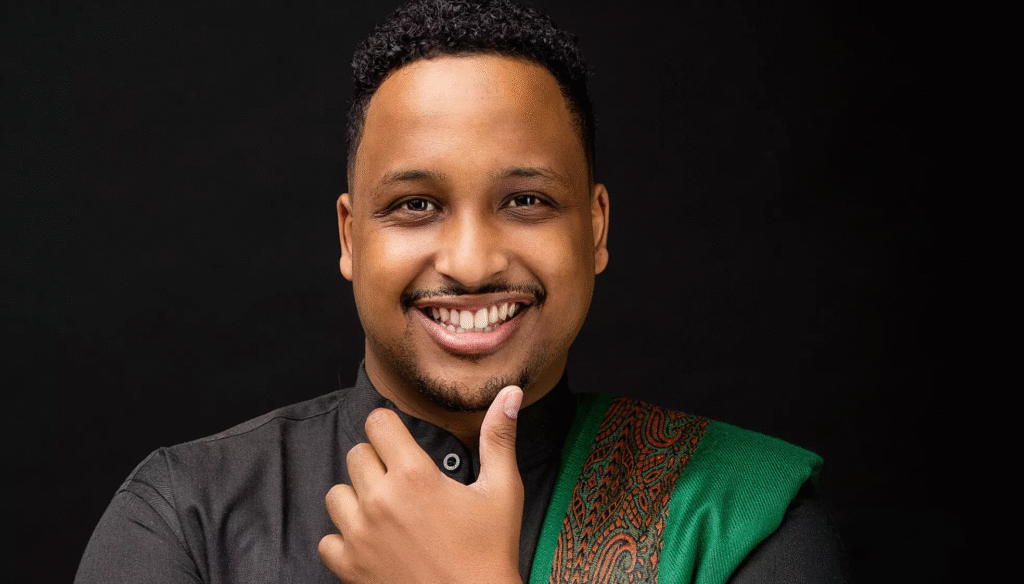

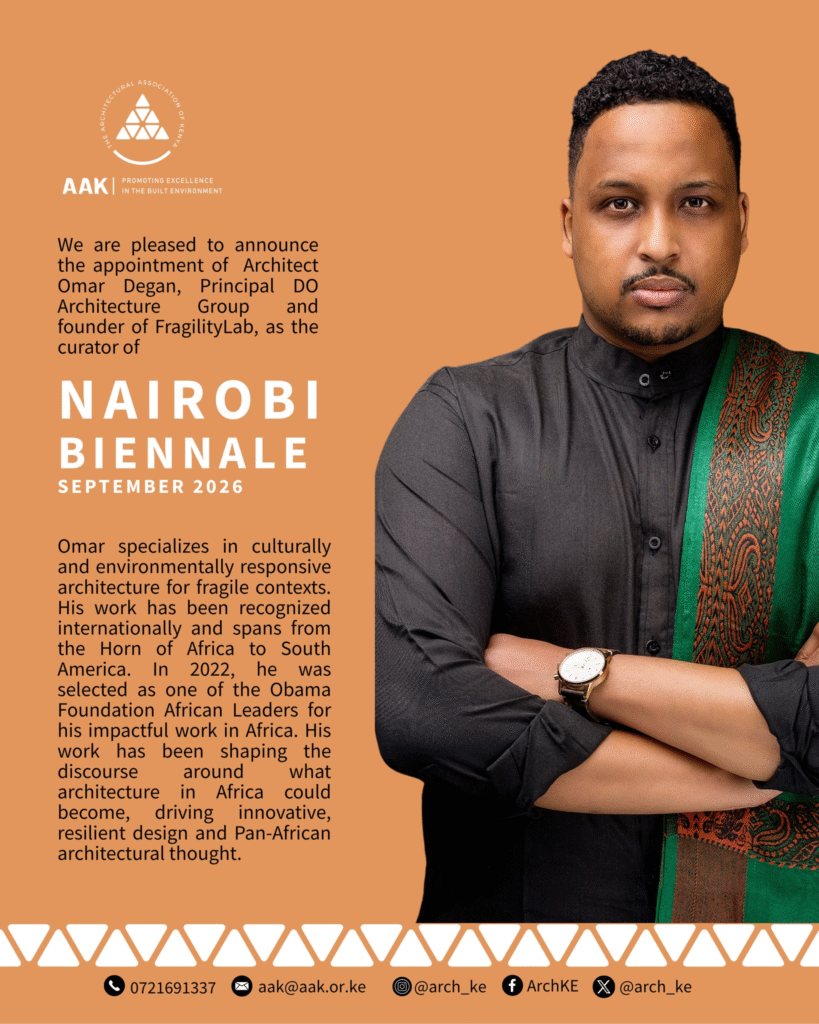

Somali Italian architect Omar Degan, curator of the upcoming Pan-African Architecture Biennale set for Nairobi in 2026, alongside his design of the Wave House in Hargeisa, Somaliland (right), a project that blends cultural heritage with climate-responsive architecture.

This will be the first architectural biennale of it’s kind in that it will be fully conceptualized, curated, and led by Africans. With 54 National Pavillions representing each African country, as well as contributions from African Diaspora, the biennale positions architecture as a political and cultural tool for rewriting how African cities and identities are imagined and built. The theme of the Inaugural edition is “From Fragility to Resilience”.

With roots in both Mogadishu and Milan, and a career that spans creating for conflict zones and refugee camps, Degan brings a perspective that is as global as it is grounded. His vision is ambitious: not only to shift the center of architectural discourse toward the continent, but also to plant the seed for a global cultural movement that may spark new school of thought, design languages and institutions across Africa.

Set to debut in Nairobi in September 2026, the biennale marks the first continent wide-platform where African architects and thinkers reclaims authorship over their built environments and their influence on global design.

Omar Degan, the Somali-Italian architect and curator spearheading the ffirs-ever Pan-African Architecture Biennale.

The question should be: What does it mean to reshape the world through African Eyes, African memories, and African materials?

For Somali-Italian architect Omar Degan, such questions are the foundation of Pan-African Biennale of Architecture, which he has envisioned and it’s positioning as a fully African-led platform for architectural thought. The biennale is a call to re-centre Africa in a long conversation dominated by Western aesthetics and narratives.

“Architecture has always been White and male-dominated”, Degan says. “Africa is the only continent that has been neglected…and even when architecture is celebrated, it is exoticized like safari lodges designed for the Western gaze”.

Degan gave reasons why architecture is political, why Nairobi is the right home for this biennale, and how he hopes it will inspire a new generation of African creators and thinkers.

INTERVIEWER: The Upcoming biennale is billed to include conversations about identity, post–colonial legacy, and African futures. Why is architecture the right platform to have these kinds of discussions?

Kenyatta International Convention Centre, Nairobi

Omar Degan: Africa is always treated as one homogeneous place, not a continent of 54 nations. Even when African architecture is celebrated, it is exoticized like safari lodges designed for the Western gaze. We need to move past that. This biennale is a space of resistance: against colonial legacies, historical neglect, and even internal elitism that distorts our narrative.

A Bold Vision for African Architecture

The Pan-African Architecture Biennale, spearheaded by the Architectural Association of Kenya (AAK) and its president, George A. Ndege, aims to challenge the global narrative that often marginalizes African contributions to architecture. Degan, the founding architect of DO Architecture Group and author of Mogadishu through the Eyes of an Architect (2020), envisions the event as a platform to reclaim African agency in shaping the built environment. Drawing inspiration from Kwame Nkrumah’s call for African unity, the biennale’s curatorial statement emphasizes a dialectic between memory and innovation, survival and imagination.

“This is not just an exhibition—it’s a political act,” Degan said in an interview with Wallpaper. “Africa is not developing; it is recovering from centuries of colonial extraction and misrepresentation. We are here to showcase African-led solutions, to reject Western validation, and to position the continent as the center of global architectural discourse.”

The biennale’s theme, From Fragility to Resilience, reflects this mission. It will highlight African innovation in sustainable design, resilient urbanism, and cultural preservation, addressing critical issues such as land rights, climate crises, and displacement. Projects will draw from vernacular traditions and indigenous technologies, such as earth construction and water harvesting, while fostering radical thought and pan-African solidarity.

The event’s structure is designed to be dynamic and inclusive, featuring:

- 54 national exhibitions, showcasing each African country’s architectural contributions.

- Keynotes and roundtables led by African and diasporic architects, activists, and thinkers.

- Workshops and community installations engaging Nairobi’s residents and the broader region.

- Civic and cultural events, including performances and public rituals, to root the biennale in everyday life.

- Collateral events organized by institutions and collectives across Africa and beyond.

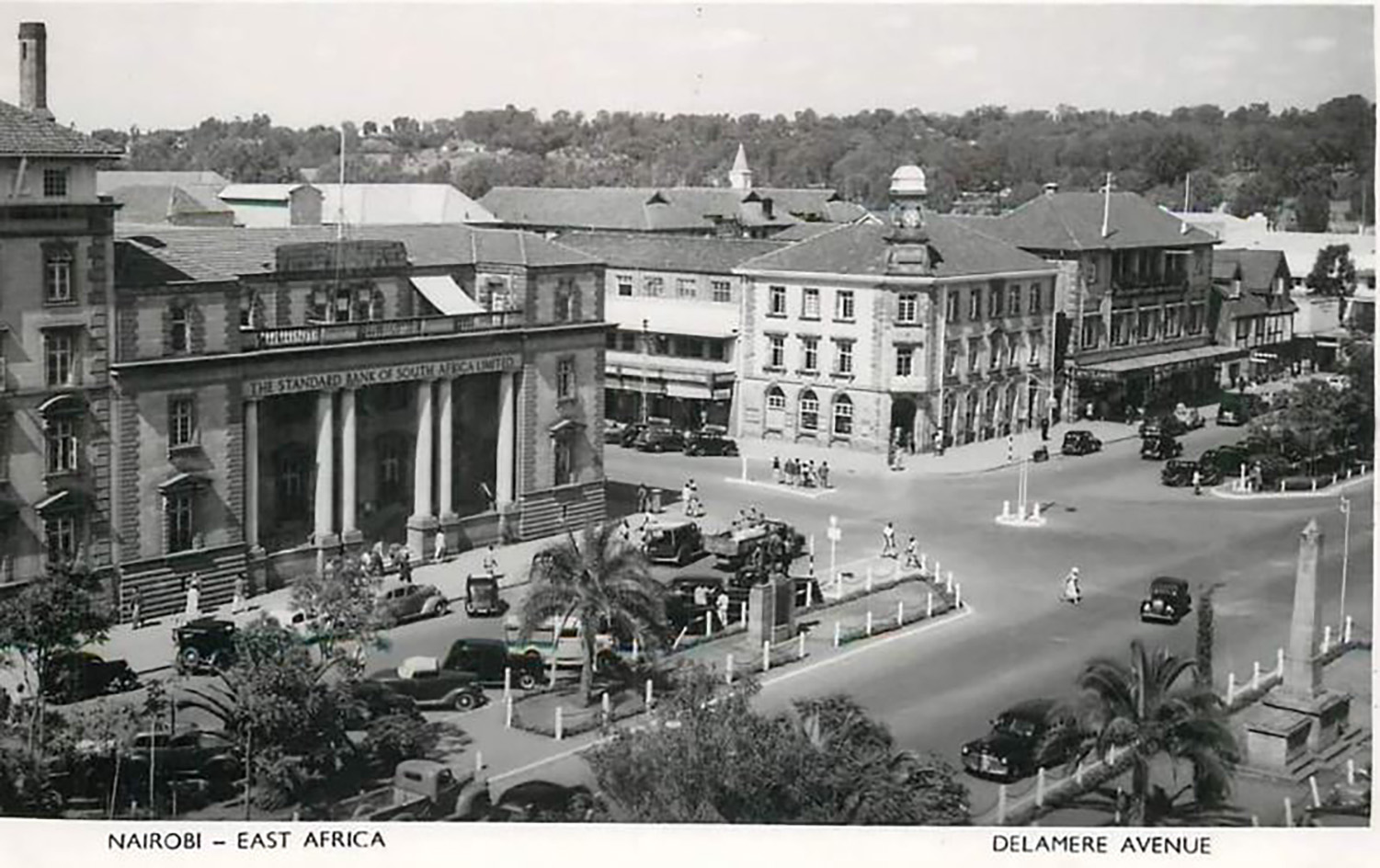

We forget how much the built environments affects us. We spent over 80 percent of our lives inside buildings. That alone should be a reason to talk about architecture. But beyond that, architecture has been instrumental in both oppression and liberation. Beautiful cities make people safe and joyful. But colonialism used architecture to control people, and many African cities still reflects that till this day.

Wave House in Hargeisa, Somaliland, designed by Somali Italian architect Omar Degan

How do you go about centering Africa in a field that has historically responded to the West.

Truth is we are not just centering Africa as it is today. We are recognizing it as the origin of civilization. That means there will be no foreign pavillions. We will have 54 pavillions, one for each African country, plus diasporic and extra-continental contributions. But even then, most of those voices will be rooted in Blackness.

There won’t be, for example, a French pavillion. But there will be participation from people with African descent who are based in France. What people will see in this biennale is that Africa is present both on the continent and through it’s diaspora. The diaspora plays a very important role in shaping Africa, just as Africa has shaped other nations. And being Black is not being a minority everywhere. In Brazil, for example, 55 percent of the population is Black, so there will be representation from there too.

What sparked the idea of the Pan-African Architecture Biennale for you personally?

I grew up Somali-Italian and studied architecture in Italy. My school actually had a rare global focus on Global South. But when I started submitting my work, I realized there were no real African architectural publications or platforms. I had to rely on Western ones, judged by the standards of Rome, Paris, London……

Then I saw the Venice Biennale being called “The African Biennale”. That was it for me. I thought, I thought, “How are we still letting the West defines us? Why should a European event be the one telling African Stories?” That moment really hit me. I said, if we want to be taken seriously, we need to create our own spaces. A place where we are not an after thought, but the starting point. That’s when I started thinking about Pan-African Architecture Biennale.

these stories. People are tired of the one-sided narrative.

A Symbolic Venue for a Historic Event

Designed by architects Karl Henrik Nøstvik and David Mutiso, the KICC opened in 1973, a decade after Kenya’s independence from British colonial rule. The building’s design merges Brutalist principles with Indigenous Kenyan influences, featuring a concrete plinth that supports a futuristic tower topped with a disc for natural shading. Its plenary amphitheater, inspired by the conical thatched homes of rural Kenya, and terracotta-clad exterior make it an architectural icon of pan-African unity. As Degan notes, the KICC’s historical and symbolic significance—coupled with Kenya’s recent policy of visa-free access for most African nationals—makes it an ideal stage for this unprecedented gathering.

“This is a deeply symbolic site, built in the early years of Kenya’s independence,” Degan told The Architect’s Newspaper. “It embodies the spirit of pan-Africanism, and hosting the biennale here sends a clear message: Africa is open, accessible, and ready to lead.”

We are still a year out from the event. How has the idea been received?

You know what? Some people have asked me “How are you going to find architect from every African country?” And I always say: “just because you don’t know them doesn’t mean they don’t exist”. That kind of thinking reflects ignorance. There is a hunger to tell these stories. People are tired of the one-sided narrative.

Why did you choose Nairobi as the host city?

I personally did not want this to default to Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa, which are the usual countries when people think of Africa. I wanted to shift the geographical center, too.

Nairobi works because it is accessible to the continent. Kenyas and Rwandans have some of the most visa-friendly policies for other Africans. Plus, the Kenyatta International Convention Centre (KICC), [which will host the event,] has powerful symbolism. It was part of the Pan-African movement. And Kenya, which was once a major British colony, now gets to host something to shoe that we have moved beyond that.

I am workin with the AArchitectural Association of Kenya as the hosting organization. I somehow convinced them to take this role, and the President, George Ndege, is very intent in reshaping the role of Architectural Association of Kenya as a lead organization in African movement.

biennale will connect those experiences. It is about showing that migration is not an absence. It is a part of our story.

What will set this biennale apart from Others?

First of all, every pavillion will have equal space, no matter how big or rich the country is. Nigeria will get the same space as Botswana. That is non-negotiable.

Second, we are incorporating sensorial experiences. I want people to smell, hear, and feel African spaces. I don’t want them to just take a selfie and leave. And part of the exhibition will be focused on African futures, with contributions from Afro-futurist writers, and sci-fi creators, and people working on AI and design. We are not just referencing the past. We are building the future.

Kenyatta International Convention Centre, Nairobi

Can you speak more to the role the African diaspora plays in this vision?

Definitely A big one. Diasporan often lived in between. They are not African enough to be African, not Western enough to be Western. But they are some of the strongest advocates for the continent. They carries these stories wherever they go, often with pride. This biennale will connects those experiences. It is about showing that Migration is not an absence. It is a part of our story.

You are Somali and Italian, trained in Architecture in the West, but deeply invested in African Spaces. How has that shaped your approach to architecture?

I’ve always lived in between worlds. I was born in Italy, but my identity was always linked to Somalia, that duality made me aware, from a young age, of how space and design can either welcome you or make you feel excluded.

My work in Somalia, and later in places like refugee camps or conflict zones, taught me that Architecture is never neutral. It reflects power, identity, and memory. That’s why I don’t just see myself as a designer of buildings. I see myself as someone trying to rebuild dignity One structure, One Story, One Space at a time.

BRIEF SUMMARY ON THE CURATOR OMAR DEGAN

Omar Degan (born June 1990) is an Italian-born Somali architect, author and academic, he is the principal and founder of DO Architecture Group. Known for his work in Africa and in particular in the horn of Africa, Omar specialized in fragile contexts and urban resilience with a particular focus on minorities and marginalized communities. His work aims to highlight the beauty of our cultural diversity and how architecture could become a means to support peace, development and fight against climate change.

Early life and education

Degan was born in Italy to Somali and Italian parents in June 1990. He studied architecture first at the Politecnico di Torino, and later at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Career

Following graduate school, Degan worked on projects to upgrade slums in Buenos Aires and Hong Kong.

Born in Italy in 1990, Omar dedicated his career to the study of emergency contexts and developing countries focusing on the interactions between cultural diversity and architecture as a mean to support the fight against climate change. The principle of his firm, which is based between Somalia, USA and Italy, lies in designing culturally, historically and climatically relevant solutions to social problems around the world, with a particular focus on the most vulnerable communities and minorities. With his work, he seeks to develop new ways to celebrate the cultural identity of communities around the world through the use of architecture, supporting peace, development and a more sustainable future. In his Tedx “Architecture Identity and Reconstructing Somalia,” he highlighted the power of culture and traditions in architecture and how design can become a tool to promote peace and development around the world. His work has been recognized internationally and has been considered one of the emergent voices of African architecture. His projects include a schools, restaurants and private houses. In 2021 due to the medical crisis in Somalia he designed a portable clinic to facilitate medical aids in rural areas.

In 2017 he received attention for his proposed memorial to the 14 October 2017 Mogadishu bombings.

In 2020 he published the book Mogadishu through the eyes of an architect.

The Pan-African Architecture Biennale will run in Nairobi and started since September 1, 2026

A Somali café by Omar Degan supports community in Mogadishu

Arbe, a Somali café by Omar Degan, offers a gathering hub for the community in Mogadishu in 2023

A new Somali café, Arbe, has been completed in Mogadishu. The space, created by locally based, Somali-Italian architect Omar Degan, was conceived as a key hub to support the neighbourhood’s community in one of Somalia’s most populous cities.

Degan explains: ‘Mogadishu is one of the most fragile cities in the world, but also one of the most resilient, and I think that the story of this city could be an example of how communities work towards a more sustainable and resilient future.’

Arbe: a Somali café by Omar Degan

‘Arbe café wants to respond to the need for spaces for gatherings [within the local community] while challenging the usual design style of restaurants and cafés within the city,’ explains Degan. Located in the heart of Mogadishu’s financial district, the space is defined by its large, arched windows, conceived to connect inside and outside. ‘The arches are inspired by what was once the gold market of Mogadishu, which was located in the historical centre of the city, Xamarweyne – an important market that was characterised by a big central square and porches with round white arches,’ the architect continues.

The bar counter is made out of recycled wood from old furniture and floor planks. A selection of local potted plants serve as a reminder that this was once a very green city. ‘The combination of the palm trees and the white façade with the arches are a tribute to what was Mogadishu before the civil war, a city named the “white pearl of the Indian Ocean” due to the green of the palm trees, the white of the buildings and the blue of the Indian ocean,’ writes Degan.

Degan leads an architecture practice in the country, founded in 2017. He has completed projects such as the multifunctional, leisure and cultural space Salsabii in the city’s Laba Dhagax neighbourhood – aiming to highlight the rich cultural identity and heritage of Somalia.

His work is defined by his passion for Somali culture; this is also expressed in his recently published architecture book, Mogadishu through the eyes of an architect, which offers an engaging tour of the country’s capital through key modern and historical buildings.