When the Nigerian writer Dami Ajayi co-founded Saraba Magazines in 2009 alongside fellow writer Emmanuel Iduma, they were at the door way of a Renaissance in the African Literature Ecosystem. The internet as just exploding in Nigeria, and ambitious writers were taking advantage of it’s global connectivity to build mostly online publications and literary townhalls.

Writers like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Binyavanga Wainana, Tope Folarin, Noviolet Boluwayo, and Teju Cole were gaining recognition on the international literary scene. Soon, other publications like Expound, Praxis, Omenana Magazine, Bakwa, Munyori Journal, and Jalada Africa began to emerge. It was the era of Afro-politans, a term coined by Taiye Selasi to explain the globally mobile and culturally aware African, which saw a blending of worlds between African writers in the West and those on the continent. Attention from the West on African Literature was blossoming and so was a local taste for change. Essentially it was a great time to be an African writer.

The Late 2000s to late 2010s were an era of vibrant publications, literary prizes and the emergence of incredible literary talents. All that has been replaced with a loss of community and dwindling literary spaces… A key part of what defined the AfricanLiteratureEcosystem in the 2010s was that it established a kind of cycle for many African writers.

“People were interested in books, people who read, people who wrote were able to come together, meet writers that they would never met previously”. Ajayi says.

At the time, there was a sufficient level of incentive to be an African Writer, whether material or reputational. “There were numerous blogs for genre fiction, literary fiction, Poetry, and creative non-fiction” says Enajite Efemuaye, a writer and editor who previously worked at Fafarina Books, one of the foremost publishers of African literary fiction with a roster filled with writers like Chimamanda, Caine-Prize winner E.C Osundu, Etisalat Prize Literature winner Jowhor Ile, Akwaeke Emezi, Yewande Omotosho and Others.

A Brief Biography by Dr. Dami Ajayi

My name is Dami Ajayi. I studied medicine and surgery in Nigeria. I trained in psychiatry at the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital, Lagos. I am a member of the West African College of Physicians and the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Dami Ajayi is a Nigerian-born music writer, poet and psychiatrist based in the United Kingdom..

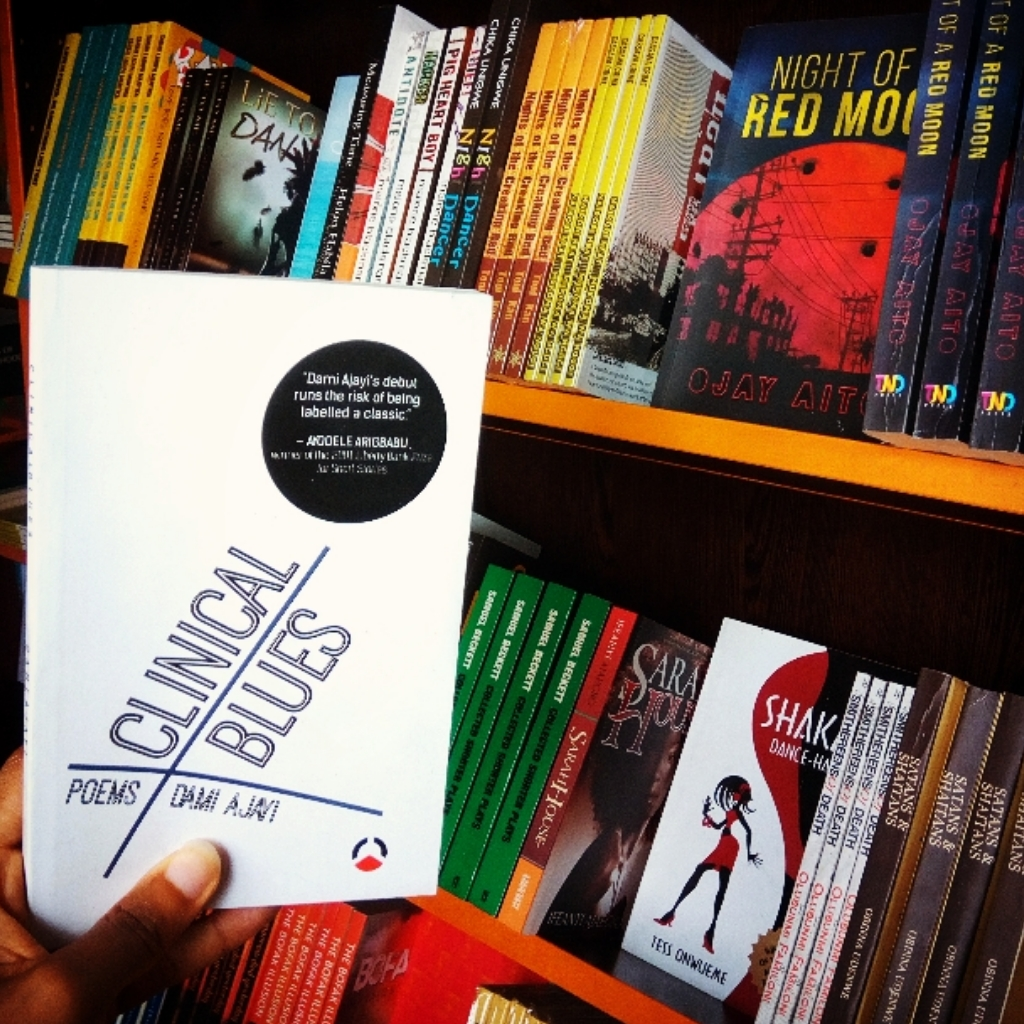

My first volume of poems, Clinical Blues (Write House, 2014), was shortlisted for the inaugural Melita Hume Prize in 2012 in manuscript form. It was also longlisted for the Wole Soyinka Prize for African Literature in 2017 and named First Runner Up for Association of Nigerian Authors Prize in 2015.

My second volume, A Woman’s Body is a Country (Ouida Books, 2017), was a finalist of the Glenna Luschei Prize in 2018. Bernadine Evaristo, the prize judge, remarked about me, “A dexterous and versatile poet who flexes his linguistic muscles with surprising revelations that offer new perspectives as he illuminates the slips between memory and desire, family, community, and place.”

My third book, Affection & Other Accidents (Radi8, 2022), was named the bestselling book of poems in 2022 by Open Magazine and Roving Heights Bookshop, Nigeria. It was also named as the best poetry collection at the Port Harcourt Poetry Festival in 2023.

I curated and co-edited Limbe to Lagos: Creative Non-fiction from Nigeria and Cameroon, published in Africa and North America, and praised by Ellah Wakatama as being “at the forefront of a wave of African non-fiction writing – an area that has long lacked representation.”

My fiction has appeared online in ITCH magazine, Kalahari Review, AFREADA, Brittle Paper, and in print anthologies Gambit: Newer African Writing and Songhai 12: New Voices of Nigerian Literature.

I have written about music consistently since 2007. What initially began as an opportunity to explore a non-literary interest has become a passion for music writing, particularly for Afrobeats, a genre of music that developed as I came of age.

I was hired as the music critic by OlisaTV magazine and wrote weekly music reviews and feature articles from 2014 to 2016. Then I was headhunted to write “The Good Doctor,” a weekly column on music for the culture blog, This is Lagos, from 2017 to 2019. I co-founded an online culture magazine, The Lagos Review, in 2019 and until recently served as an editor.

My essays and commentary on music and culture have appeared in the Africa Report, Chimurenga Chronic, Afropolitan Vibes Magazine, Lost in Lagos Magazine, Global Voices, Music in Africa, The Republic, The Elephant and elsewhere.

I have been consulted for music writing in feature articles in the Financial Times, African Arguments, Al Jazeera, The World and Weekendavisen.

“You had writing communities on websites and social media, which served as spaces for writers to get honest critique on their works, feedback, and encouragement,” Efemuaye says “These communities fueled and challenged the writers, and as a reader, you could see the quality of writing from the writers improves over time because they weren’t working in the Silos. They were also reading and having conversations about writing, which is important for any literary ecosystem.”

A Comprehensive Interview with the Managing Editor of Farafina Books, Enajite Efemuaye Talks Writing and Publishing in Nigeria

Farafina Books — the literary imprint of publishing house, Kachifo Limited — is home to books by Nigerian authors Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Lesley Nneka Arimah, and Ben Okri, amongst others. I spoke to their managing editor, Enajite Efemuaye about her (very cool) job, how she got there, her work in training editors, and book publishing in Nigeria.

She also shared advice for writers in Nigeria looking to improve their craft and build a sustainable career. I loved reading Jite’s answers and I think her advice for writers is spot on!

What do you do for a living and what does your job entail?

I read for a living. That’s the answer I like to give even though what I do is a lot more than that. I’m the managing editor at Kachifo Limited. Most people know us by our literary imprint, Farafina.

I’m like the production manager at a factory with books as the final product. I work with a team of editors, graphic artists, illustrators and sometimes photographers and translators. I also work with writers, agents, and other publishers. This means I send and receive a lot of emails.

How did you end up working as a managing editor at a Nigerian publishing house?

In 2016, I had just quit my job as editor at Sabinews (at the time owned by Toni Kan and Peju Akande) to go back to school for a masters degree when I was invited to temp as an editor at Farafina because the managing editor was going on a road trip around Nigeria with Invisible Borders. After the two-month stint, I was offered a full-time position, and I took it. I started as the enterprise editor, which saw me managing the publishing services imprint, Prestige and when my boss left for grad school, I was promoted to managing editor.

Before Sabinews, I spent two and a half years volunteering with a youth development NGO in Nnewi Anambra state. Before that, I was a graphic artist/editor at a print press in Awka Anambra state for about three years.

What is your favorite part of your job?

The favorite part of my job is reading a manuscript that blows my mind from the first chapter. We get tons of submissions, and most of them are really bad. So when I get a book like Of Women and Frogs by Bisi Adjapon from the submissions editor, it’s like getting soft ponmo from the ewa agoyin woman who is notorious for jaw-breaking ponmo. Another favorite part of my job is the spontaneous conversations we often have about literature and all the gentle shade we throw at writers and readers.

Which parts of your job are the most “stressful”?

I can’t really think of any particular part of my job that is stressful. There are stressful situations from time to time, and that happens when you’re working with deadlines, but nothing specific to the job that I’d consider stressful.

What do many people not know about the publishing industry in Nigeria? What would you change about it if you could?

Publishing is a business first and foremost. We worry about the bottom line like other businesses. We face the same challenges with power and poor infrastructure and government policies and corruption. That we work with books does not put us in a celestial plane.

Very little about the publishing industry in Nigeria is unique to it when you look at it as a business. If I could change anything, I’d make it easier to do business in Nigeria. I’d fix the educational system. Build libraries in every local government. Make sure people have enough to eat so buying books stops being a frivolous luxury for many.

I know you’re passionate about training more editors. What’s the motivation behind that passion?

I am a mostly self-taught editor. I learned by doing, googling a lot of things, taking paid online courses. I want to take the knowledge I have gathered and pass it on — even if it’s just to give directions on where to go for what kind of resource. I didn’t have anyone doing that for me and it made the learning process in the early days somewhat difficult. It doesn’t have to be.

Also, we don’t have enough good editors in Nigeria and I would like to see that change.

What do you think writers and editors could do to improve their craft? What advice would you give them about navigating the world of writing and building a sustainable career?

They should stop folding their arms and expecting to be spoon-fed success. There is so much talent that won’t lead anywhere because the people who house them don’t think self-development is important. They believe in “inspiration” and the “muse.”

So, I’ll say, read. Read a lot more than you’re writing. Read good writing. Read classic and contemporary literature. Read romance and memoirs. Read profiles and essays about food.

Research on your own. Find out how the publishing process works. Keep your eyes peeled for opportunities.

Network. This doesn’t necessarily mean form cliques, but cliques are not all a bad thing if you spend the time helping and challenging yourselves. Attend literary events – book readings and launches, festivals and so on.

Do the work. And put yourself out there as much as you can.

Would you consider yourself a morning or night person? What three things are part of your morning routine?

I’m a morning person. I go to bed as early as 9 p.m. and I’m up at 3 a.m. I do my morning devotion, read emails and check my notifications on social media.

What do you like to do in your spare time?

It goes without saying that I read a lot in my spare time. I also watch Netflix and YouTube and stare into space.

What is the future of the Nigerian publishing industry? Can we expect any cool things from Farafina this year?

The Nigerian publishing industry is a many-pronged thing. There are publishers of educational books, religious books, fiction and so on. I honestly cannot predict the future of the industry. We just plan for it as much as we’re able to.

I will say though, that a lot more people are self-publishing and that’s a good thing for the industry.

Aren’t we always doing cool things?

Enajite Efemuaye is the managing editor at Kachifo Limited, an independent publishing house in Lagos Nigeria. She is a sometimes writer and retired graphic artist, with a chemical engineering degree which she has never used.

All of this began to change as the late 2010s rolled around. Lack of funding and economic hardships intensified across the continent, particularly in countries like Nigeria, which was regarded as a forerunner in the African Literary space. Highly regarded publications like Saraba, which published writers like T.J Benson and Ironsen Okojie, began to fold-up (Saraba halted operations in 2019, but an archive of it’s public works remains live). Online literary communities began to vanish, shuttering spaces for communal critique and avenues to discover new exciting voices.

More than a decade since that glorious era, the African literary ecosystem is now experiencing a drawn-out lull, what Kenyan Writer and editor Troy Onyango describes as “the silent era”.

Onyango himself emerged during that golden era of African Literature. First, as a writer before co-funding one of the most Prestigious publications at that time, Enkare Review. Enkare Review, during it’s time, published esteemed authors like Namwali Serpell, as well as an interview with David Remnick, the editor-in-Chief of The New Yorker. It was an audacious publication that bravely brought the international community to Africa, offering up a lineup of brilliant voices with each issue. The publication folded up in 2019, it’s third year in operation.

And while Onyango has gone on to experience immense literary success and has now founded Lolwe, one of the very few African literary magazines still in operation, there is according to him, a clear distinction between the quality of work being submitted now and 10 years ago.

“The quality of work has gone down,” Onyango says. “even the output. We used to have African writer’s publish 10-15 short stories in a year. And that’s one single writer. I published about 8 stories in 1 year. And now we no longer see that. We see one or two people publish like maybe three stories max, or four stories max,”

Another important aspect of that cycle was collective responsibility. African writers who achieved success were known to give back, often by supporting existing publications, mentoring emergence writers, or even founding their own publications and prizes to nurture other literary talents. There is now a break in that cycle.

There are significantly fewer Literary African publications in operation now than they were six years ago. Alongside Lolwe, publications like Akpata magazines, The Republic magazines, Brittle Paper, Open Country Magazines, and Isele Magazines are amongst the few enduring platforms still holding the fort. In Nigeria, book publishing has shifted from literary works to commercially driven titles, with publishers like Farafina, Cassava Republic, and Parréssia publishers scaling back their operations and publishing fewer titles. In Kenya and other parts of the continent, book publishing continues to dwindle. And most dangerously,the online spaces that facilitated healthy conversations in favor of the Ecosystem have All but disappeared.

Many of the people who were part of that Era, like Ajayi and Efemuaye, says the decline can be traced back to 2020. In Nigeria’s case, many of the brilliant writers of that Era suddenly found themselves compelled to pursue better opportunities outside the country after leaving through a disastrous economy and experiencingthe 2020 #ENDSARS protests. Between 2022 and 2023, more than 3.6 million people emigrated from Nigeria, according to Nigeria’s Immigration Service.

“Culture is the first casualty of a credit crunch and it’s the first thing to go,” Ajayi says. “When the economy began to collapse, and ENDSARS happened, a brain drain that had already begun to intensified. So everyone who had the wherewithal to move, moved.” As Ajayi sees it, these writers are still dealing with the task of adjusting to new realities, which often forces them to solely focus on their work and their survival, leaving little room to contribute to the well-being of a dying industry.

Onyango believes that funding and economic upheavals have long plagued the industry; however it’s not the only thing currently stymying it. There is a dearth of dialogue that has also contributed immensely, Onayonga offers, “Younger writers are coming up, and they don’t see writers of the previous generation, when writers were on social media, they would produce all these essays. They would have blogs. I don’t even remember the last time I read a blog. I don’t even know if people still blog anymore.”

This vacuum of conversations has created a chasm of Understanding between OLD and NEW writers.

As JudithAtibi, a TV anchor and producer who has hosted numerous literary shows and events, sees it, this lull is costing the literary community. “We are losing richness that comes from rigorous editorial systems, spaces where a writer could be challenged, and with Challenges comes Growth. Atibi says.

“We are losing the diversity of voices, regionally, linguistically, and experimentally. Literary careers are not being nurtured in a way that builds longevity.”

According to Efemuaye, “Writers learn craft through multiple rounds of editing and feedback from editors since their work had to meet certain editorial standards. These thorough editorial processes are being replaced by the instant gratification that comes with self-publishing because writer’s bypass the developmental stage of working with Skilled Editors who can help them refine their voice and writing styles”.

The effects are already showing. Books are expensive, and book prizes, which once boosted Sales, are no longer available, leaving many African writers to compete with those still living in the West. And in the Past Five years no African Writer has been nominated for the Booker Prize.

Despite the dire state of things, Ajayi is optimistic. And according to him the way forward is to hold institutions accountable. While individuals should build what they can, Ajayi believes the administrative support will go a long way in subsidizing the cost of running literary institutions in the interest of preserving literary traditions and keeping the arts alive especially in times like these.

And as Onyango sees it, the way to avoid this lull is by institutionalizing African Literary Spaces so they are formidable enough to last beyond whoever funded them. The first step to overcoming this lull is to acknowledge the problem while also recognizing that small support for the few existing Literary publications and institutions can go a long way. The best kind of support isn’t always in funding.

“We need to be more conscious about how we build structures that outlasts the founders,” Onyango says. “I don’t get why we are not more involved in the building. Even if you are not able to build your literary magazine, even just saying, “I volunteer 20 hours a month at ISELE Magazine just editing; it’s very helpful!

In conclusion, African Writers needs to be more involved in the literary production process that just the creative aspect. Editors are needed and need to be trained, It is just not enough to have people who Writes.

KEY NOTES TO TAKE HOME

Nigerian writers Dami Ajayi and Enajite Efemuaye have discussed the challenges facing African literature, thus attributing the continuous decline of the African Literature Ecosystem to a lack of Institutional support, insufficient patronage for writers, and societal disregard for creative expression. They highlight the deterioration of the former vibrant literary communities that once fostered growth, leading to writers being forced into “writer-for-hire” roles rather than making a sustainable living through their craft.

Key Issues for the Decline

- Lack of Institutional Support: There is a recognized need for more structured support for the literary arts, which was once provided by dynamic reading communities but is now insufficient.

- Insufficient Patronage: The literary landscape suffers from a lack of financial backing for writers, making it difficult for them to pursue writing as a sole profession.

- Societal Disregard: The societal value placed on creative expression is low, which further contributes to the lack of resources and opportunities for writers.

- Loss of Communities: A significant factor in the decline was the erosion of the strong, interconnected reading and writing communities that once thrived, providing crucial support and fostering improvement among writers.

Consequences for Writers

- “Writer-for-Hire” Roles: Many writers who remain in the field must take on various writing jobs to make ends meet, as they are unable to sustain themselves through their primary literary work.

- Unsustainable Livelihoods: The lack of robust support systems means that writing cannot be a sustainable livelihood for many, forcing them to find alternative means of income.

In essence, both Ajayi and Efemuaye point to a systemic problem where the structural and cultural conditions that once supported African literature have weakened, leaving writers to struggle for recognition and financial stability.