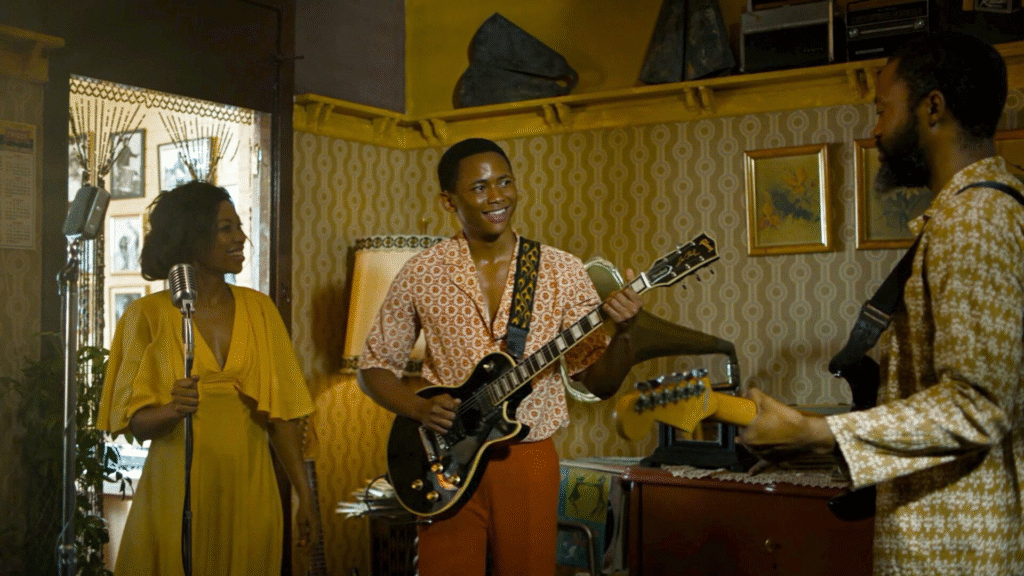

Cast member Ntobeko Sishi plays a guitar during a scene from the movie “Laundry”, which premieres September 5 at the 50th Toronto International Film Festival, in this undated handout still image obtained by Reuters on September 4, 2025. Gabriel Lobos/Handout

A unique arrangement allows protective patriarch Enoch Sithole [Siyabonga Shibe] to operate a family–owned laundry business in a part of town that is labeled whites-only. This operation soon becomes a hub for Black people in the neighborhood. Though technically allowed to work in the neighborhood, the business is not immune to intimidation by oppressive state actors. When the patriarch is targeted and imprisoned, talented sixteen-year -Khuthala [Ntobeko Sishi] takes it upon himself to free his father, even if it means deferring his own dreams of becoming a musician.

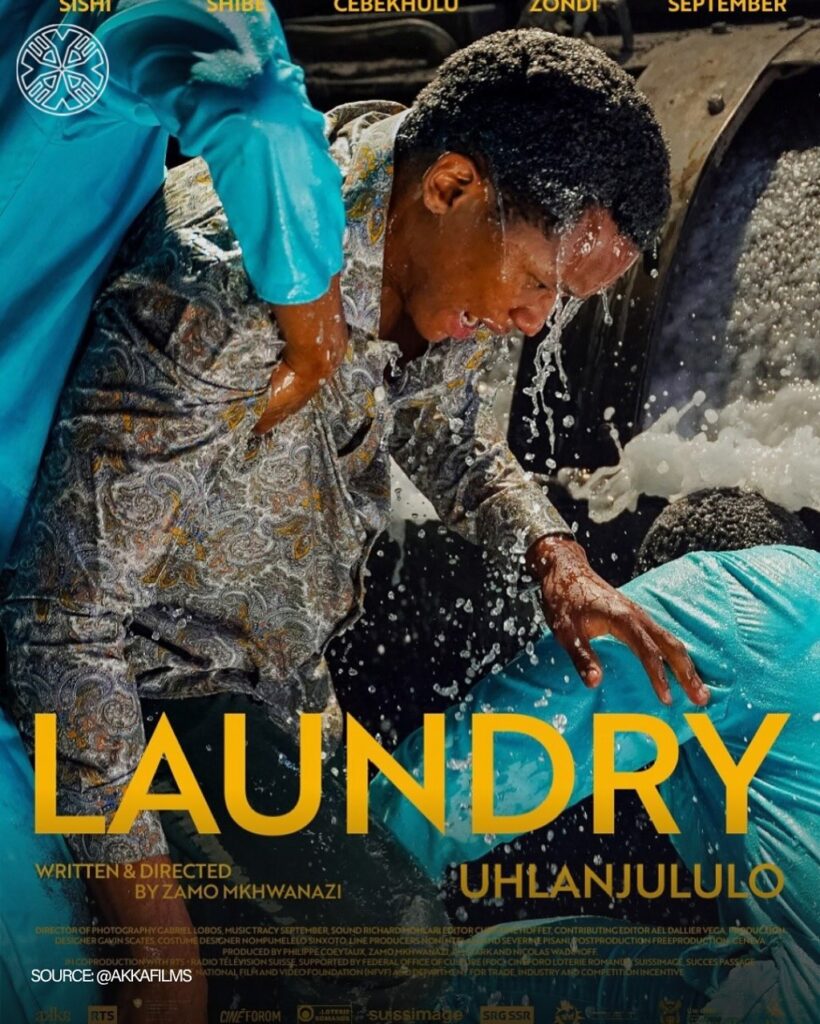

In “LAUNDRY” (UHLANJULULO), Zamo Mkhwanazi’s quietly impactful feature directorial debut, members of a Black Family navigate the social, political, and institutional tensions created by the apartheid system. Set in 1968, Laundry, which premiered in the discovery section of the On-going Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), is a potent period drama that lays bare the challenges and complexities of existing under a brutally racist regime.

This film showed at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival’s (TIFF), explores the human cost of life under an oppressive regime.

“LAUNDRY” is an Ode to artists and the freedom of chasing dreams. The film is also a sober lamentation for the unquantifiable talents lost to a system that viewed Black bodies and minds only as tools for capital.

“The laws in apartheid era South Africa were completely insane, and they were also both inconsistent and inconsistently applied,” Mkhwanazi’s says. But instead of zeroing on the specifics of these indignities, Mkhwanazi is more concerned with the human cost of the oppressive system.

“Laundry” is a sober lamentation for the unquantifiable talents lost to a system that viewed Black bodies and minds only as a “tool” for Capital.

“So–called western civilization is just theft, when you think about it. They steal, they package, they reinvent, and they sell. Music is one those things that they have tried but have never managed to steal from us.”- Zamo Mkhwanazi

Music is a constant element in the film. Enoch Sithole and his family are music connoisseurs. In a scene, Magdalena plays the piano after the day’s work. In another, Khuthala and Ntombentle bond over a speaker blasting music. Enoch supports Khuthala’s music dream. And Khuthala often falls into musical frenzy to deal with emotional stress. He also stalks Lilian (Tracy September), a popular musician. Thus, in the film, music is used as a conduit for stress and familial bond. But, politically, music is also an artistic channeling of pain and rage against the apartheid regime. Music becomes a sonical protest against the foreign establishment.

Also, there is a feeble critique of the patriarchal tendency of Enoch. Ntombentle lives and breathes the family business and not only does she love curating her life and daily activities around the laundry establishment, she’s eager to lead it. But, in Enoch’s socially-approved and patriarchal thinking, Khuthala whose mind is set on his music career, is the ideal heir. The reason is simple: he’s a man. Thus, the film also captures the cultural and institutional neglect of women in society. In another instance, Magdalena can’t bail his husband because she’s a woman. This situation exemplifies the intersection of racial and gender discrimination embedded into the apartheid government’s policies and practices. It’s a denial that reinforces the patriarchal nature of the apartheid regime where women’s public and social roles are controlled. Additionally, it’s a minute indication of the broader systemic inequalities that apartheid enforced, not only along racial lines but also along gender lines. Mkhwanazi’s script glances through these subjects but for the women living these systemic injustices, it limits their economic and personal freedom.

The writing is lacking in most cases. The film frames Enoch’s absence upon his arrest as inspiring chaos and doom into the business. Suddenly, the once peaceful and organized business is running into the ground and once-faithful workers are now rebelling, recalcitrant and stealing from the business. What makes it unbelievable is how, before his arrest, the script doesn’t convey how Enoch’s presence substantially adds to the day-to-day running of the business. Neither does his presence inspire loyalty and discipline amongst workers. Thus, the script’s inability to express this adds a major narrative dent to the film. Until the third act, it isn’t consciously conveyed, the psychological burden Enoch’s arrest has on his family. Enoch’s children and wife are given the air of tourists in their own active history.

Dean Meyers (Robert Whitehead ), a White official, is on Enoch’s payroll. Dean Meyers arms Enoch with necessary documents to triumph over institutional take over. For two decades, this arrangement moves undetected. Prior to Enoch’s arrest, Dean Meyers is portrayed as an unreachable White government official. After Enoch’s arrest, it’s mind-boggling how Khuthala easily gets in contact with him. Another narrative flaw is how the film floats through core political, institutional and personal issues but isn’t able to thread them together.

Zamo Mkhwanazi’s ‘Laundry’ is a potent period drama that lays bare the challenges and complexities of existing under a brutally racist regime.TIFF

How did this idea Crystallize?

Zamo Mkhwanazi: This film is inspired by something that happened to my mother’s family. My grandfather owned a laundry, and in 1954, about six years into the apartheid government, the business was taken away from him, he lost his Livelihood.

The “LAUNDRY” is a key character in the film, and there’s this sense of connection with the space that can be gleaned from the way you filmed it.

It basically has to do with the luck that we had finding this “laundry” that has basically been running since 1949. They still had a lot of the same equipment from the earlier days. But because it is a really big business, we also had to make the location into a family space. The balance we had to find was how to make this industrial–scale operation with big machinery a small enough space to be able to tell an intimate story. Our Production designer, Gavin Scates, was clever, and we had to find very creative ways of hiding modern machinery. This I think, helped create a sense of coziness and depth.

The Cinematography is Ravishing. The actors are photographed so beautifully, but also the spaces and the props. Tells us more about the virtual designs.

I have a very real and strong artistic appreciation of Black skin as a Canvas. This is an aesthetic level, separate from the political. Siyabonga Shibe, who plays the father, Enoch, has got the most beautiful skin complexion, that there was really no kind of lighting that could go wrong on him. When we were grading the film, we had to stop looking at him because he makes everything just looks so nice. It is a pleasure for me to look at Black skin, and because we haven’t seen nearly enough images of us on screen, there’s still much space to explore.

“Laundry” is a period piece. How do you approach creating this world for the screen?

The film was shot in Boksburg and Benoni, east of Johannesburg. It is one of those things where the negative comes with the positive because these are economically depressed areas that have not attracted a lot of investment over the years. A lot of Architecture and Infrastructure still looks the same from back in the day. We were able to find quite a small radius of space, and this allowed us to minimize the amount of work we would’ve done otherwise. The exteriors were there. We then had to do more work on the interior spaces, but even some of them we could work with. Production design was key; we had to get props, classic vehicles, wardrobe, etc.

Is there a particular reason you chose to set the film in 1968, and why does that period speak to you?

1968 marks the end of the sixties and heralds the beginning of the seventies, and to me, that was a pivotal time in South Africa history. The Sharpville Massacre of 1960 was a sort of turning point, as it happened at the same time African countries were getting their liberation through independence. So, there was this understanding that the work wasn’t done. I remember older people telling me that there was huge optimism for the rest of the continent, and there was South Africa in contrast, which remained in the belly of the beast.

For me, this was interesting because it was a key moment in South African history, African history, but also in global Black history. Artists at the time were escaping into exile, were they were speaking out and working extensively for the cause. Miriam Makeba went to the United Nations and hung out with the Black Panthers.

It was a moment of choice for a lot of people: do you leave your home and fight abroad, or do you stay behind and fight the system from within? 1968 was also the year that Martin Luther King Jnr. was assassinated and the year of the summer olympics, with the Black American athletes who held their fists up in protest. The seventies were around the corner, and we know that the seventies were also a period of huge turmoil in South Africa. I wanted to touch the Optimism of the continent that maybe freedom was possible. It felt like it was the right moment to place the Characters.

From a character perspective, how does Khuthala’s musical ambition function as both personal expression and political act in the context of 1968?

I do not believe anyone wakes up in the morning wishing to fight a system or to fight oppression. What people wake up wanting to do is to fight for their dreams. I chose a commonplace dream. Not particularly admirable like being a doctor, or realistic like running a laundry or noble like being a teacher. Just an ordinary, somewhat selfish, possibly foolish dream.

In the context of a world where black bodies were actively being turned into industrial fodder, a dream that does not create goods and services is the antithesis of a body that is meant to be an input of production.

The film also captures the specific cultural and socio-political tensions of the era. The “Dompas,” for instance, was a thing….

The Group Area Act is basically the law you see in action in the film. It states that Black people may not live or own a business in certain areas. But it is a thing that has not entirely worked. This Apartheid-era is notable for how much of it did not work, or worked very badly. Sometimes people just circumvented, ignored, or just kept going until someone physically took them out. That is the kind of resistance that I also wanted to highlight.

A lot of resistance is just ignoring the oppressors and their laws and doing whatever it is you need to do in order to survive. I wanted to put a sense of those laws into the film, but at the same time, I didn’t want to spend a lot of time showing how the system functioned or the specifics of how these laws were applied. I wanted to create a sense of unease so that the audience can understand that mere existing, or walking from Point A to B, is fraught with danger.

And I know that these kinds of things have happened in so many places in the world under different names. Even at the airport, the brown people with their green passports are all waiting in line for two hours while the whites in their blue passport breezes through.

And you have to behave a certain way in line, waiting…….

Exactly. You police yourself even before anyone talks to you. You cannot even asks a question because you know that there will be punishment for you just wanting information. I want you to have the same feeling you do at the airports.

Music is a key part of the film and I am sure you will hear this often, but the film reminded me on some level of Ryan Coggler’s “SINNERS”.

This is the greatest compliment, and no one has said this to me.

The laundry business becomes a gathering place for the Black community in the film. How important was it to show these spaces of connection and mutual support within the oppressive system?

The laundry is a place where they are served according to when they arrive, as opposed to most places where whites would always be served first. This is never explicitly mentioned, but is clear in the way customers line up when Enoch is present. It is also important to make it clear that while the area is declared white, most of the people given patronage or working in the area are black.

Apartheid was incredibly nonsensical; a capitalist system that thought it could thrive by keeping the majority of consumers without any buying power. So places like this laundry show that these laws were nigh to impossible to maintain.

After exploring your family’s past so intimately in Laundry, how has this experience changed your approach to storytelling and what stories you want to tell next?

What changed the most for me was when I had the screening here (in Toronto). Honestly, putting the work in front of an audience that connected so strongly with the work assured me that the issues that interest me remain relevant, even as I feel that political storytelling from Africa, particularly stories that challenge white supremacy, are being strongly discouraged both locally and in the international festival space.

Having an audience that responded to the story with enthusiastic appreciation of the difficult themes was a blessing. My next project retains a strongly political point of view, with feminist themes. It’s set in the future and concerns bodily autonomy.

But it does. Music becomes this “tool” of resistance, and you do have this scene in your film that demonstrates how the music is born out of pain and struggle, literally.

I had to do music, I am South African. I’m sorry. I am not even trying to fight my own conditioning. It’s like “what else can I do?” I often say that music in South Africa is like mustard in Dijon. Everyone’s life in South Africa is touched by or connected to music in some way. Someone asked me if I have musicians in my family, and my response was that everyone in South Africa does. We all qualify for that one.

I also have a great regard for artists in general. That ability to create something out of nothing and to have that creation spread and touch people’s life and make a difference to them, for me, that is a miracle. South African musicians during the Apartheid era did their part, especially when you think about how small the country is in terms of numbers and the things that were taken from us – and they took everything.

I wanted to make a film about something that could not be taken away. So-called western civilization is just theft when you think about it. They steal, they package, they reinvent, and sell. Music is one of those things that they have tried but never managed to steal from us. Even when you see someone else singing that song, it will never be the same. It just cannot be replicated. The artists cannot be replicated.