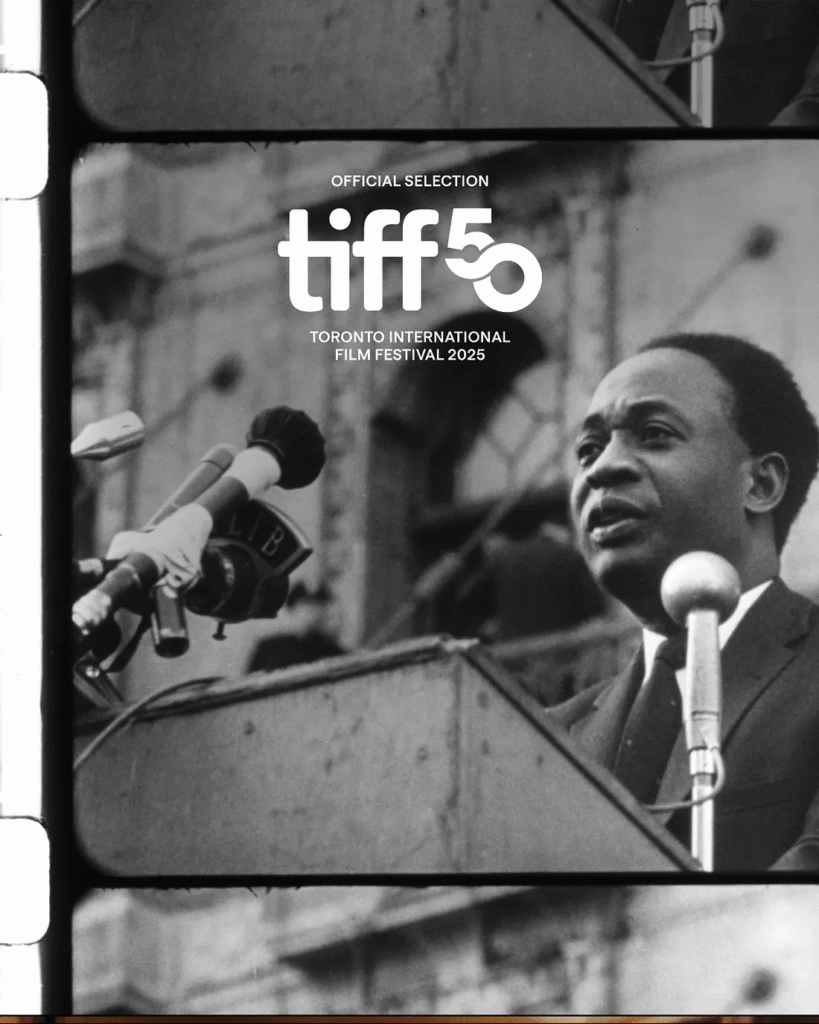

Over 50 years since his death and nearly 60 years after his overthrow, Kwame Nkrumah’s vision for not just Ghana, but Africa at large has played a massive role in Barrack and Michelle Obama- produced documentary, THE EYES OF GHANA directed by Ben Proudfoot. The film, which made it’s World Premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival as the Opening documentary, has received enthusiastic reviews.

While studying in the United States at Lincoln University, a historically Black college in Pennsylvania, Nkrumah saw the role Cinema played on American Life and Culture. That realization played a crucial role in how he governed Ghana and interacted with other African Leaders, who, at the time, were seeking to gain independence for their own countries, just as Ghana had. That is why he established the Ghana Film Industry Corporation (GFIC), and he shared his philosophy and mission with Rev. Chris Hesse, the Cinematographer and Filmmaker who documented his life and travels as President. And who is often referred to as the protagonist in The Eyes of Ghana

BELOW IS A MUST WATCH INTERVIEW… THE INTRIGUES, THE PULSATING CRINGING TRUTHS AFRICAN REVOLUTIONALIST GO-THROUGH….mehnnnn!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

“There was a sense of urgency in the way [Kwame Nkrumah] wanted this to happen: ‘Let’s have a viable film industry. Let’s reverse the image that the colonizers showed. Let’s build our own film industry and show us in a much better light.’” – Anita Afonu.

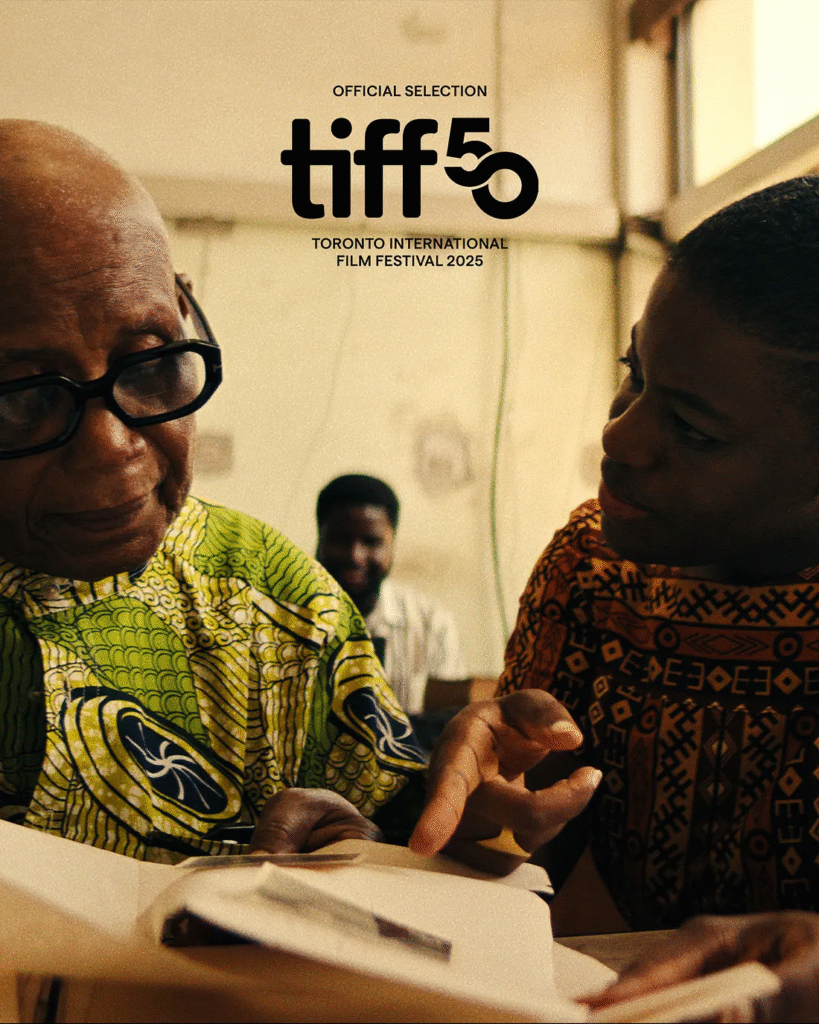

The film is about Chris Tsui Hesse, aged 93 now, who was Nkrumah’s personal cinematographer and film chronicler for Ghana’s early years of independence. It is from the eyes (both literal and metaphorical) of Hesse that we catch a glimpse of a youthful independent Ghana: a country resolved that it had to tell its own stories in an attempt to reverse the colonial stereotypes. Hesse chronicled not only political events and speeches, but talks with world leaders, journeys across newly independent Africa, and the texture of daily life in a government teeming with promise.

Proudfoot and his team members found out that Hesse, who is now 93 years old, is the keeper of Kwame Nkrumah’s belief that cinema was a key component to shaping African Liberation.

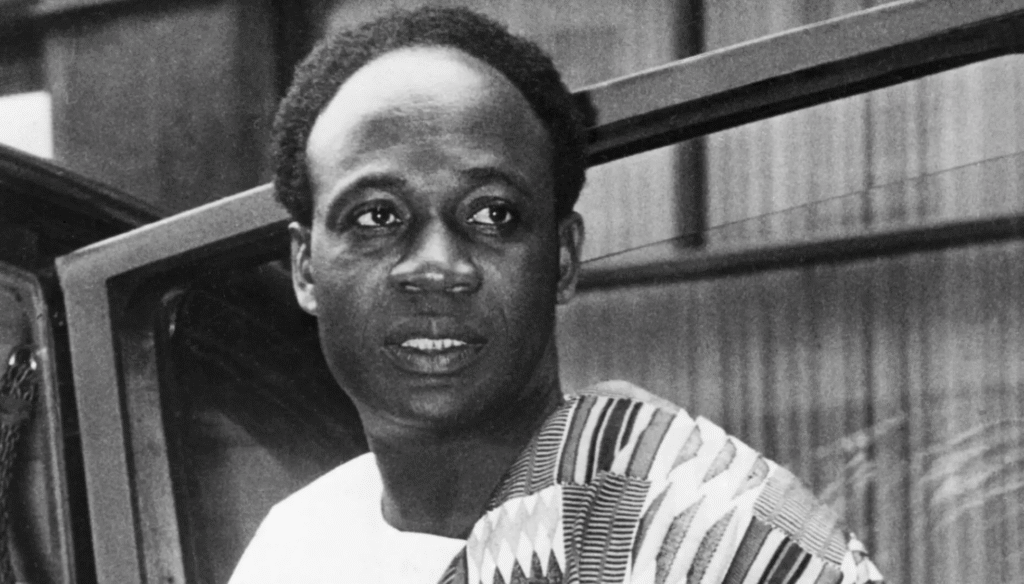

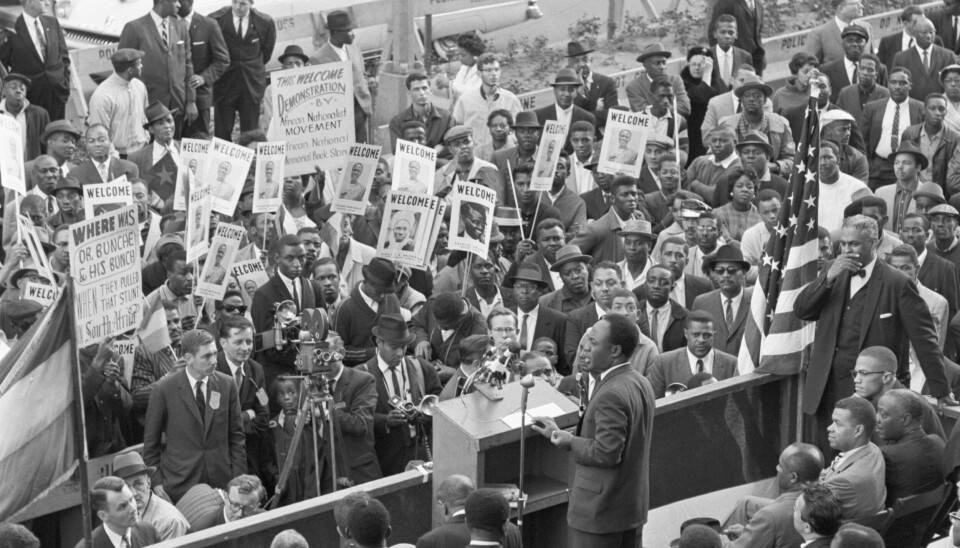

The first President of Ghana Kwame Nkrumah

Unlike other documentaries, Hesse doesn’t just speak to the camera, instead we learn of the message, and mission organically through his grandfatherly relationship with fellow filmmaker Anita Afonu, who is also one of the documentary producers

Afonu’s 2013 40-minute short film Perished Diamonds, featuring Hesse and Edward Addo, who worked as a Projectionist, for the outdoor Rex Theatre in Accra, helped Proudfoot, and fellow producer Nana Adwoa Frimpong find a foundation for THE EYES OF GHANA. “Ben (Proudfoot) would say he couldn’t have made this film without Anita [Afonu], Frimpong says.

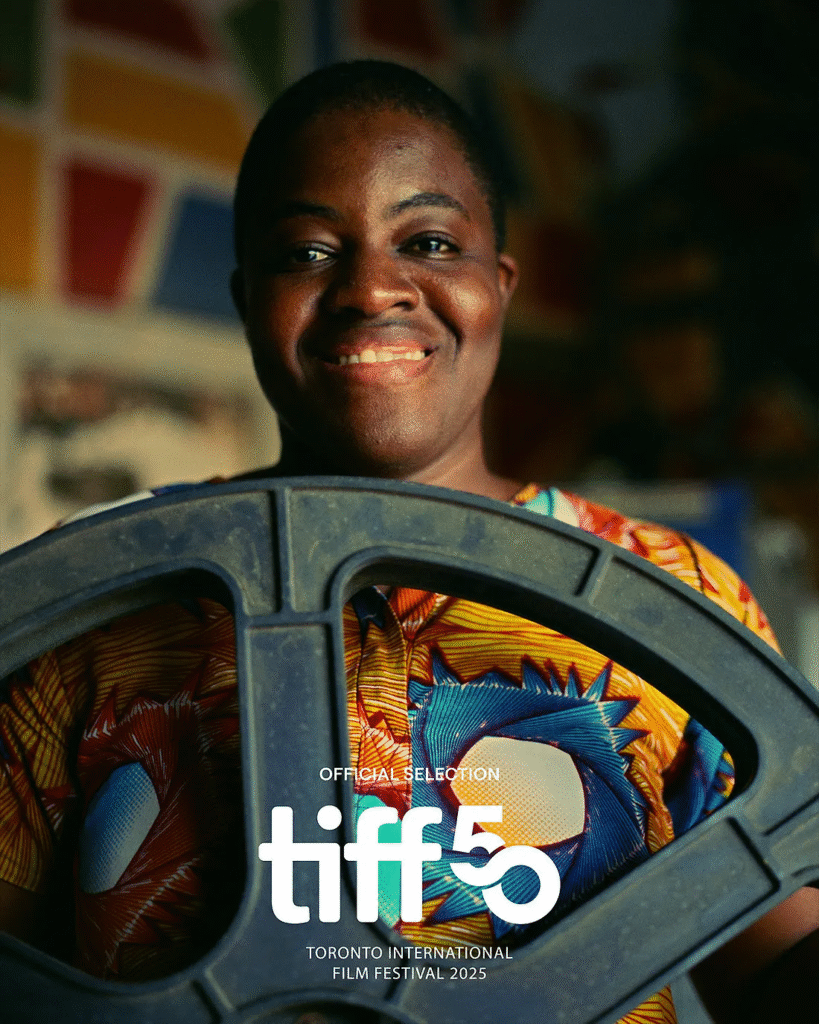

Filmmaker Anita Afonu

But this reclaim had its glitches. Some of Hesse’s film reels were thought to be destroyed or lost in the aftermath of political unrest. The Eyes of Ghana reconstitutes what remains, afraid footage, restored screenings, public cinema theatres like the Rex Theatre in Accra, and pairs them with contemporary voices: Anita Afonu, filmmaker and producer, and “Mr. Farmer-driven. Addo, the activist projectionist, rescues outdoor theatre exhibitions. These figures bridge past and present, reminding viewers this isn’t nostalgia, but a continuing struggle over control of image and memory.

A still from ‘The Eyes Of Ghana’ documentary showing celebrated cinematographer Chris Hesse wearing a yellow, brown, blue, and green-patterned African print shirt and smiling.

Working with former U.S. President Barack Obama and Higher Ground Production was also Organic, Frimpong says. “I remember we had a meeting about it and was like, well “who is sort of this access point [for the film], and it was Barack Obama, like the African and the American. And there is also the fact that Kwame Nkrumah was inspired by African American Civil rights leaders. So it was like it goes bothways, and we had worked with Higher Ground on another film, and they had been great partners there, and so, when we brought this to them, they were like, “Yeah, we see a connection here.”

As the daughter of Ghanian immigrants to Canada, Frimpong is also very personally connected to the documentary, “This film has really felt like an invitation for me to really get curious about where I come from,” Frimpong says, who grew up as one of the handful of Black students in her schools until she went to college in Toronto.

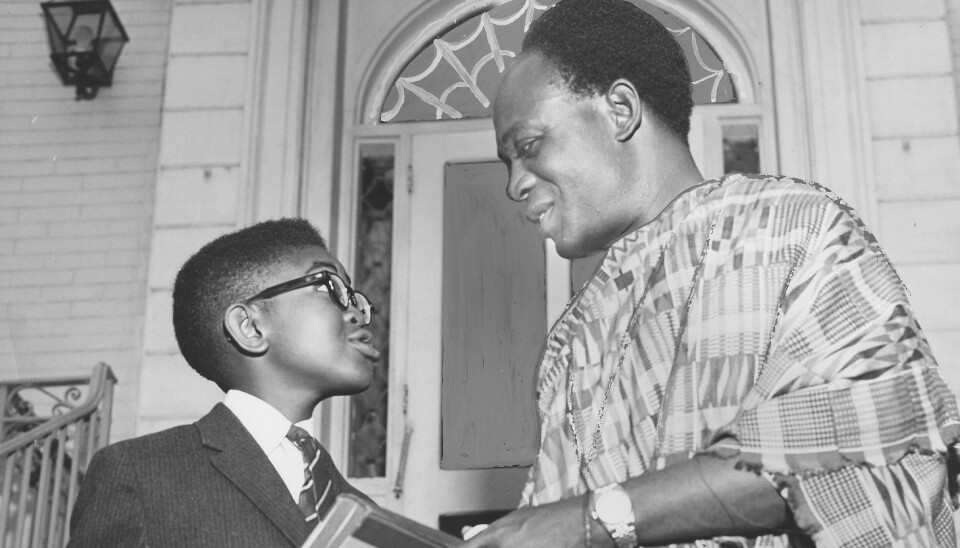

Filmmakers Chris Hesse and Anita Afonu

“Meeting Chris Hesse, meeting Anita [Afonu], hearing their stories, I was like, “Oh, wow. Here are people who know why this is so important, because they are literally showing us the thing that I so desperately needed and didn’t even know… When I see the people on screen dancing, and they’re joyful, and they looked like my parents, I’m like, “Okay, that’sthething that I have been searching for. That’s the range of possibilities that I’ve been hoping to see.”

Frimpong, who attended the University of Southern California Film school in Los Angeles. “I had a very limited scope of what it meant to tell a story about a Black person, about an African person, and I think it’s also because the world unfortunately expects a limited characterization of us.”

That realization is perhaps what makes Hesse shares about Nkrumah’s vision all the more powerful. Unlike Frimpong, Afonu did learn of Hesse in film school but had no idea of what a great treasure he truly was. “They talk about him, but they don’t teach about him,” she says. “But there was never any instance where he was invited to talk to us or anything like that.”

Needing to piece together her own sense of the Ghanian film industry in many ways led her to Hesse. But where Perished Diamonds focuses on Ghanian film industry as a whole, the Eyes of Ghana zones more into Hesse and Nkrumah. What viewers learn is how“Central” Nkrumah viewed cinema’s role in African Liberation, in the fight against Colonialism.

“There was a sense of urgency in the way he wanted this to happen: “Let’s have a viable film industry. Let’s reverse the image that the colonizers showed. Let’s build our own film industry and showed us in a brighter light,” She paraphrased. “We all learn about Nkrumah in history class, but it’s only like a surface scratch, something o to just pass to get to the next level. And I feel like this film is quite a history lesson, even for Ghanians.”

One of the unifying threads that runs throughout ‘The Eyes of Ghana’ is urgency. Nkrumah did not simply see film as a work of art, but as a weapon: an antidote to caricature colonialism had made of Africa. He drew inspiration from his own experience as an international student in the U.S., where he observed the impact of film on public opinion, identity, and community, and believed Ghana could establish its own film industry (the Ghana Film Industry Corporation, GFIC) to portray its people with dignity and complexity.

Hesse’s films of Nkrumah, previously believed to be destroyed, are vital to the documentary. He captures him addressing the United Nations, meeting with American President John.F.Kennedy, as well as some of his many secret meetings with Africanleaders. But the Filmmaker-turned-Reverend is very clear that what he captured was very intentional on Nkrumah’s part. In many ways, he knew that this footage would remain important long after his death. And it’s why Rex, protected by Addo, also plays an important role in the documentary.

Projectionist Edmond Addo

For Afonu, the film is coming at a great time. “I would say on the last five to eight years, there has been a resurgence of Kwame Nkrumah, especially in Ghana and especially with millennial generation,” she says. “And so with this resurgence in this film, I feel like everything is coming together do beautifully, and we’re getting to know more about Nkrumah.”

For far too many Ghanaian and diasporan individuals, ‘The Eyes of Ghana’ comes at the right time. There is renewed interest in Nkrumah, not just as myth, but as inspiration. Younger generations hungry for roots, authenticity, and auctoritas of storytelling are discovering value in these reappropriated images. Anita Afonu describes finding Hesse’s writing as an eye-opening experience: suddenly, there are possibilities of how one can write stories that feel like home, that uncover joy, struggle, hope, and all the in-betweens.

That doesn’t necessarily means Afonu views Nkrumah as a god. “At the end of the day, he was a human being like everybody else. He had his flaws, but he had a vision, not just for Ghana, but for the entire Continent. It’s about how he brought all of us together. He inspired over 250 million Africans, which includes the father of the first Black President of the United States. And it shows how Nkrumah connects all of us, and it’s so beautiful,”

Although Hesse could not make the trip to the TIFF for a The Eyes of Ghana’s World Premiere, his excitement over the rediscovery of not just his work but Nkrumah’s vision is felt all over the film. Hesse’s joy as a person is just infectuous. His recognition as an important conduit of history through filmmaking matters greatly to Afonu.

“I am incredibly grateful that this film has been made while he’s still with us. It would have been a real shame for this film to be a Posthumous kind of thing,” she says. “God forbid if he even left tomorrow, I am at peace knowing that he got to see a cut, and he was happy with it.”