Born James Ngugi on January 5, 1938, in Kamiriithu, near Limuru, Kiambu district of Kenya, he developed a reputation as a revolutionary Kenyan novelist, playwright, essayist and academic and one of the biggest shapers of African literature. He advocated for the African continent and his home country to free itself from Western cultural dominance.

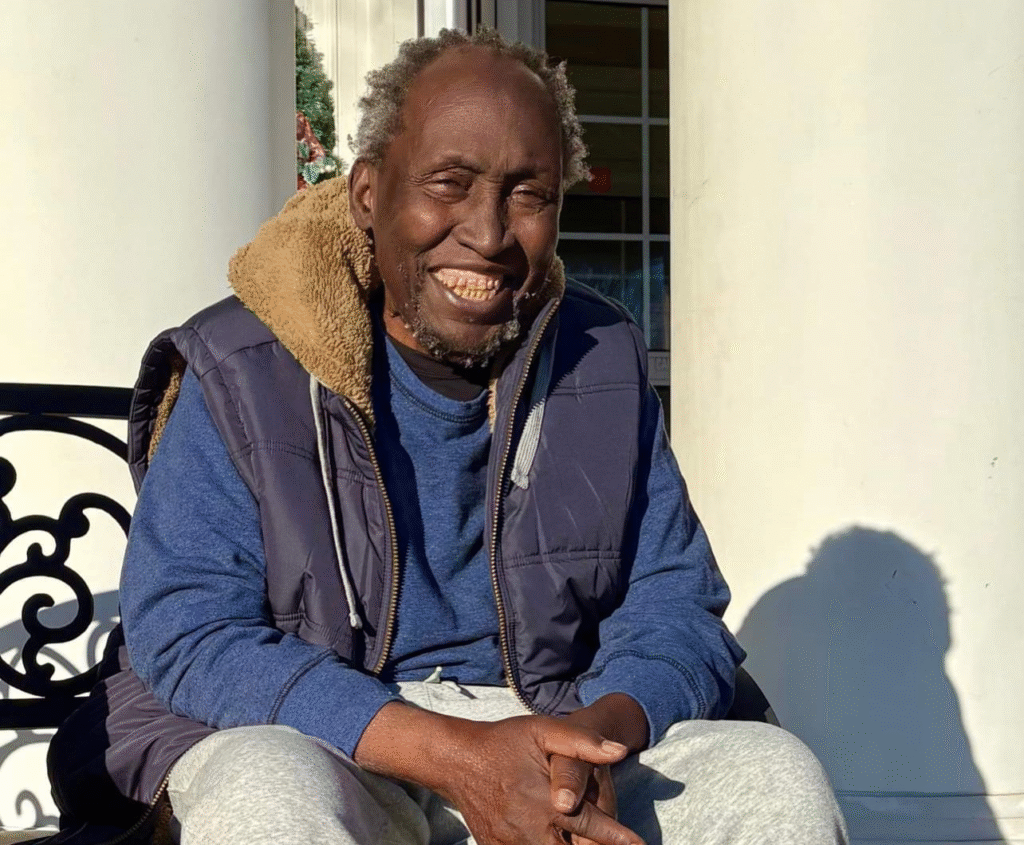

On Wednesday May 28th, 2025, the family of the great Kenyan Author Ngūgī Wa Thiong’o announced that he had passed away at the age of 87. He left behind one of the most iconic legacies in African Literature, beginning his career in the 1960s and writing several books and plays that challenged colonialism and restored pride in local culture.

Celebrated as one of the Africa’s Greatest Wordsmiths, Kenyan Writer, Poets,and Playwright; the great Kenyan Author left behind one of the most iconic legacies in the world.

Here INTALKS.AFRICA explores why he’s an ‘enduring man of letters’ and speaks to the writers that he influences.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s intergenerational influence emanated from his ground-breaking literary works and advocacy for cultural decolonization, particularly his push to write in African Languages like ”Gikuyu” to reclaim heritage and liberate consciousness from colonial dominance. As a literary pioneer, he used storytelling to challenge oppressive regimes and empower marginalized communities, creating a lasting legacy that inspires writers and activists to fight for cultural freedom and express themselves in their mother tongues.

Early years and education

Ngũgĩ was born on 5 January 1938 in Kamiriithu, near Limuru in Kiambu district, Kenya Colony of the British Empire. He is of Kikuyu descent, and was baptised James Ngugi. His father, Thiong’o wa Ndūcũ, had four wives and 28 children; Ngũgĩ was born to his third wife, Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ. His family were farmers whose land had been repossessed under the British Imperial Land Act of 1915. During Ngũgĩ’s childhood, they were caught up in the 1952–1960 Mau Mau Uprising; his half-brother Mwangi was actively involved in the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (in which he was killed), another brother was shot during the State of Emergency, and his mother was tortured at the Kamiriithu home guard post.

Ngũgĩ left Limuru in 1955 to go to the Alliance High School, a boys’ public school about 20 kilometres away. He would later write about the scene of desolation he found on returning home after his first term there: “…the British had razed the entire village to the ground. Kenya was under State of Emergency, the colonial state’s way of trying to isolate the forces of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army, waging war against the settler state. My village destroyed, Alliance High School, for the next four years became the new base, from which I looked back at Limuru, the region of my birth. By losing my home, I became more aware of it, the home that I had lost.”

Ngũgĩ went on to study at Makerere University College in Kampala, Uganda, from 1959 to 1963, and he said it was in those years in his new country of residence that he found his voice as a writer: “The novels The River Between and Weep Not, Child were the early products of my residency in the country of my educational migration. Uganda enabled me to discover my Kenya and even relive my life in the village. I discovered my home country by being away from the home country.” As a student, he attended the African Writers Conference held at Makerere in June 1962, and his play The Black Hermit premiered as part of the event at The National Theatre. At the conference, Ngũgĩ asked Chinua Achebe to read the manuscripts of The River Between and Weep Not, Child, which were subsequently published in Heinemann’s African Writers Series, launched in London that year, with Achebe as its first advisory editor. Ngũgĩ received his B.A. degree in English from Makerere University College in 1963.

First publications and studies in England

Ngũgĩ’s debut novel, Weep Not, Child, was published in May 1964. It was the first novel in English to be published by an African writer from East Africa.

Later that year, having won a scholarship to the University of Leeds to study for an MA, Ngũgĩ travelled to England, where he was when his second novel, The River Between, came out in 1965. The River Between, which has the Mau Mau Uprising as its background and describes an unhappy romance between Christians and non-Christians, was previously on Kenya’s national secondary school syllabus. He left Leeds in 1967 without completing his thesis on Caribbean literature, for which his studies had focused on George Lamming, about whom Ngũgĩ said in his 1972 collection of essays Homecoming: “He evoked for me, an unforgettable picture of a peasant revolt in a white-dominated world. And suddenly I knew that a novel could be made to speak to me, could, with a compelling urgency, touch cords [sic] deep down in me. His world was not as strange to me as that of Fielding, Defoe, Smollett, Jane Austen, George Eliot, Dickens, D. H. Lawrence.”

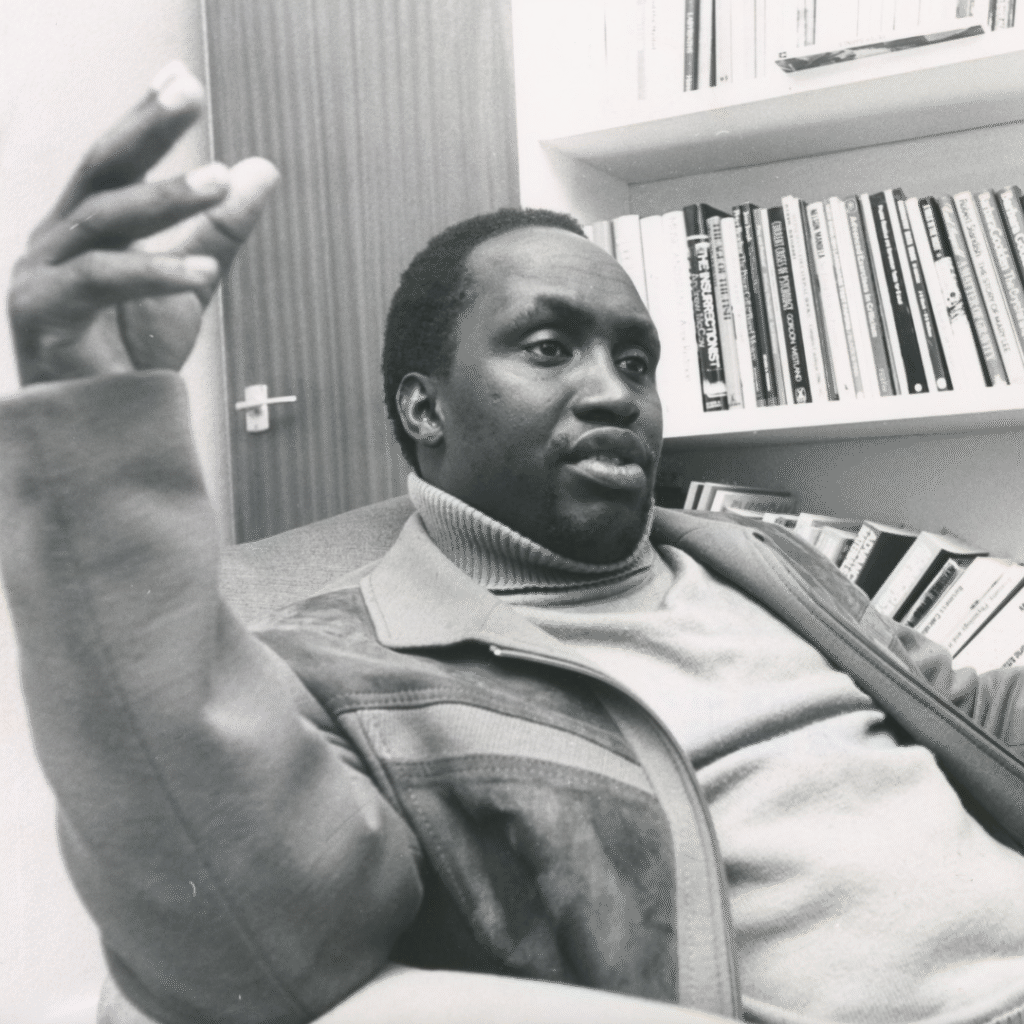

Change of name, ideology and teaching

Ngũgĩ’s 1967 novel A Grain of Wheat marked his embrace of Fanonist Marxism. He subsequently renounced writing in English, and the name James Ngugi as colonialist; by 1970 he had changed his name to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, and began to write in his native Gikuyu. In 1967, Ngũgĩ also began teaching at the University of Nairobi as a professor of English literature. He continued to teach at the university for ten years while serving as a Fellow in Creative Writing at Makerere University. During this time, he also guest-lectured at Northwestern University in the department of English and African Studies for a year.

While a professor at the University of Nairobi, Ngũgĩ was the catalyst of the discussion to abolish the English department. He argued that after the end of colonialism, it was imperative that a university in Africa teach African literature, including oral literature, and that such should be done with the realization of the richness of African languages. In the late 1960s, these efforts resulted in the university dropping English Literature as a course of study, and replacing it with one that positioned African Literature, oral, and written, at the centre.

Imprisonment

In 1976, Thiong’o helped to establish The Kamiriithu Community Education and Cultural Centre which, among other things, organised African Theatre in the area. The following year saw the publication of Petals of Blood. Its strong political message, and that of his play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), co-written with Ngũgĩ wa Mirii and also published in 1977, provoked the then Kenyan Vice-President Daniel arap Moi to order his arrest. Copies of his play, books by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin were confiscated from him. He was sent to Kamiti Maximum Security Prison, and kept there without a trial for nearly a year.

Ngũgĩ was imprisoned in a cell with other political prisoners. During part of their imprisonment, they were allowed one hour of sunlight a day. In Ngũgĩ’s words: “The compound used to be for the mentally deranged convicts before it was put to better use as a cage for ‘the politically deranged.'” He found solace in writing and wrote the first modern novel in Gikuyu, Devil on the Cross (Caitaani mũtharaba-Inĩ), on prison-issued toilet paper.

During his time in prison, Ngũgĩ decided to cease writing his plays and other works in English and began writing all his creative works in his native tongue, Gikuyu.

Ngũgĩ’s time in prison also inspired the play The Trial of Dedan Kimathi (1976). Written in collaboration with Micere Githae Mugo, The Trial of Dedan Kimathi was performed at FESTAC 77 in Lagos, Nigeria. The play recreates the indomitable courage of the Mau Mau revolutionary and his right-hand person – a woman warrior. While Kimathi remains in jail, it is ‘the woman’ – representing Kenyan mothers – who tries to free him and in turn train the next generation for the struggle. The role of Kenyan women in the Mau Mau movement (Kenyan freedom struggle) is a historical reality.”

After Ngũgĩ’s release in December 1978, he was not reinstated to his job as professor at Nairobi University, and his family was harassed. Because he wrote about the injustices of the dictatorial government at the time, Ngũgĩ and his family were forced to live in exile. Only after Daniel Arap Moi, the longest-serving Kenyan president, retired in 2002, was it safe for them to return.

Exile

While in exile, Ngũgĩ worked with the London-based Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners in Kenya (1982–98). Matigari ma Njiruungi (translated by Wangui wa Goro into English as Matigari) was published at this time. In 1984, he was a Visiting Professor at Bayreuth University, and the following year was Writer-in-Residence for the Borough of Islington in London. He also studied film at Dramatiska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden (1986).

Ngũgĩ’s later works include Detained, his prison diary (1981), Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986), an essay arguing for African writers’ expression in their native languages rather than European languages, in order to renounce lingering colonial ties and to build authentic African literature, and Matigari (translated by Wangui wa Goro), (1987), one of his most famous works, a satire based on a Gikuyu folk tale. Describing himself as a “literary migrant”, he also stated: “I had to be away from my mother tongue to discover my mother tongue.”

Ngũgĩ was Visiting Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Yale University between 1989 and 1992. In 1992, he was a guest at the Congress of South African Writers and spent time in Zwide Township with Mzi Mahola, the year he became a professor of Comparative Literature and Performance Studies at New York University, where he held the Erich Maria Remarque Chair. He served as Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature and was first director of the International Center for Writing and Translation at the University of California, Irvine.

21st century

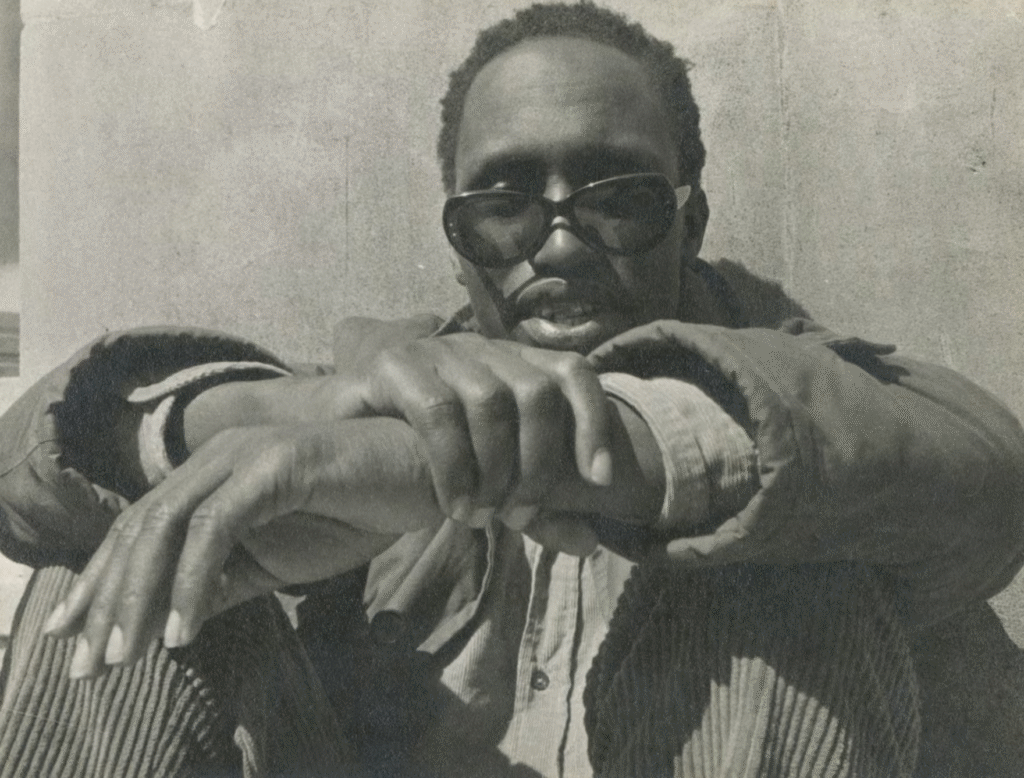

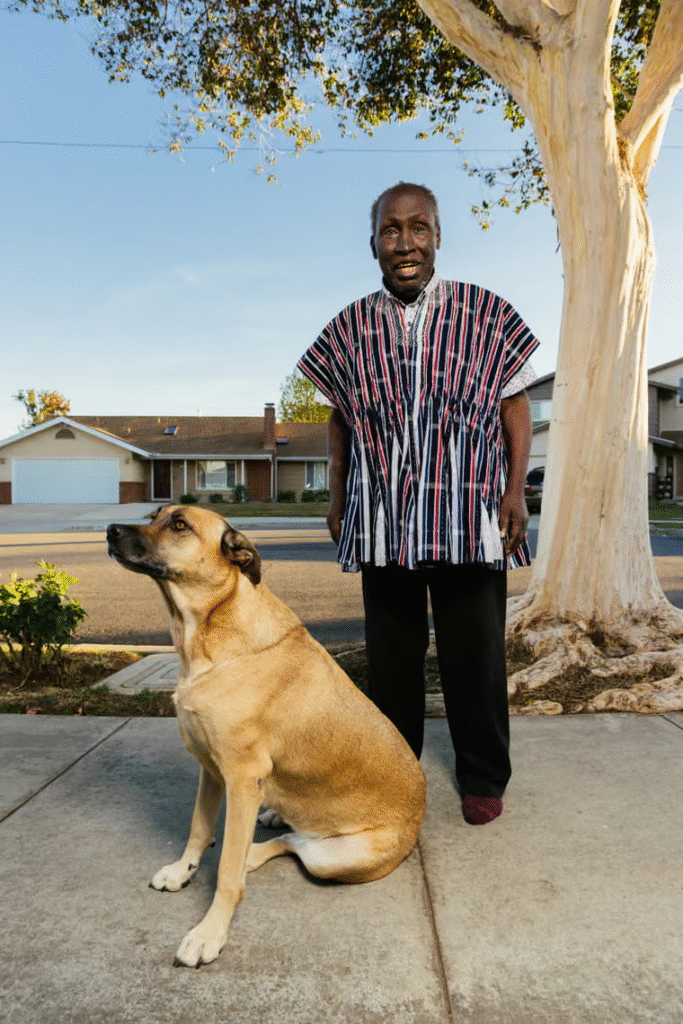

Ngũgĩ in London in 2007

On 8 August 2004, Ngũgĩ returned to Kenya as part of a month-long tour of East Africa. On 11 August, robbers broke into his high-security apartment: they assaulted Ngũgĩ, sexually assaulted his wife and stole various items of value. When Ngũgĩ returned to the U.S. at the end of his month-long trip, five men were arrested on suspicion of the crime, including one of his nephews. In 2006, the American publishing firm Random House published his first new novel in nearly two decades, Wizard of the Crow, translated to English from Gikuyu by the author himself.

On 10 November 2006, while in San Francisco at Hotel Vitale at the Embarcadero, Ngũgĩ was harassed and ordered to leave the hotel by an employee. The event led to a public outcry and angered both African-Americans and members of the African diaspora living in America, which led to an apology by the hotel.

Ngũgĩ’s later books include Globalectics: Theory and the Politics of Knowing (2012), and Something Torn and New: An African Renaissance, a collection of essays published in 2009 making the argument for the crucial role of African languages in “the resurrection of African memory”, about which Publishers Weekly said: “Ngugi’s language is fresh; the questions he raises are profound, the argument he makes is clear: ‘To starve or kill a language is to starve and kill a people’s memory bank.'” This was followed by two well-received autobiographical works: Dreams in a Time of War: a Childhood Memoir (2010) and In the House of the Interpreter: A Memoir (2012), which was described as “brilliant and essential” by the Los Angeles Times, among other positive reviews.

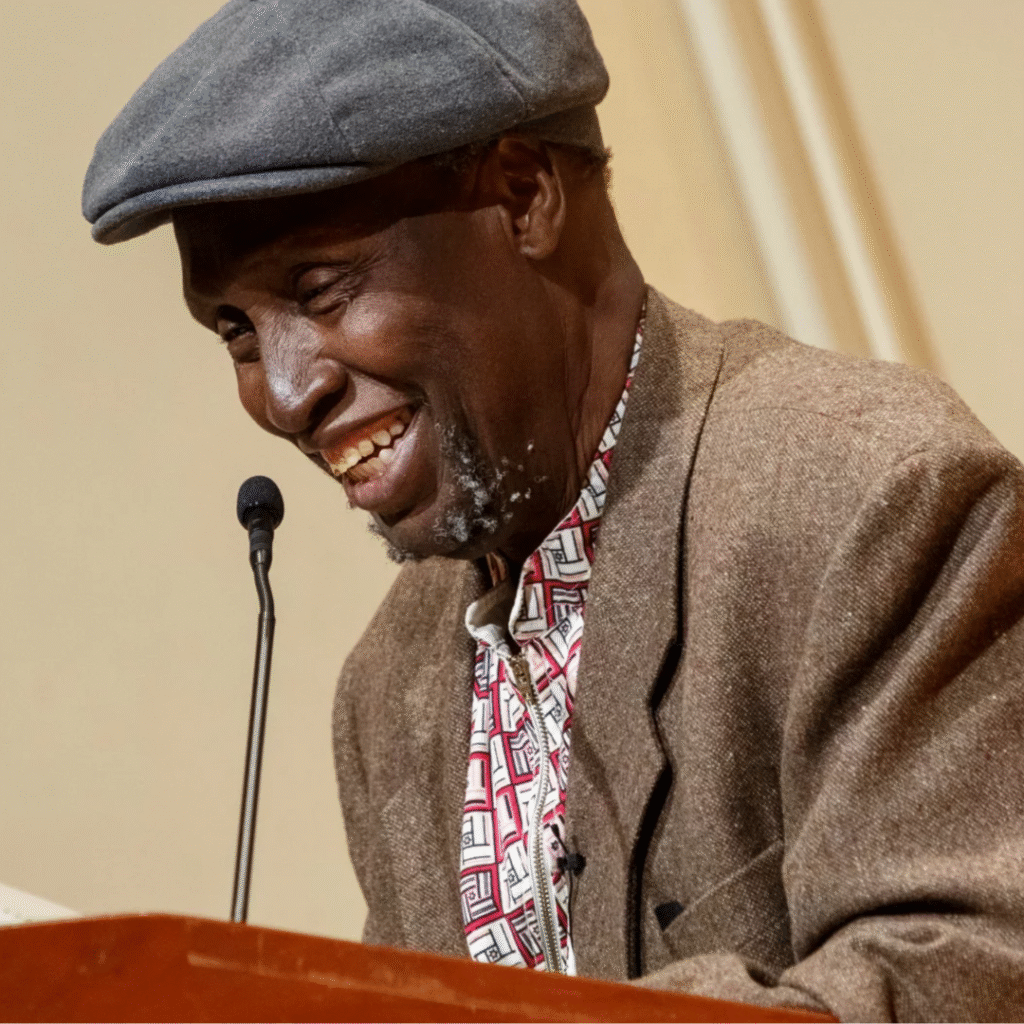

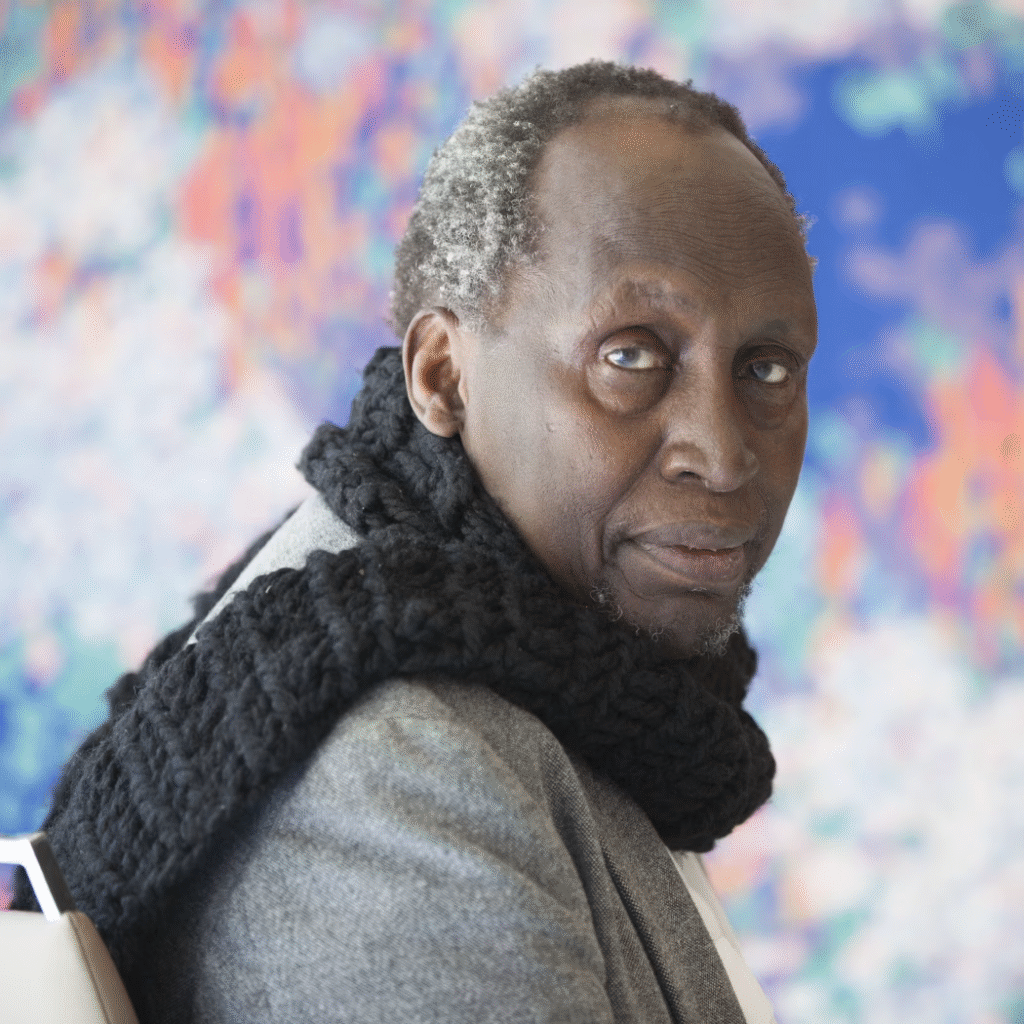

Ngũgĩ reading at the Library of Congress in 2019

There was perennial speculation about Ngũgĩ being a likely candidate to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, and he had been considered a firm favourite in 2010. However, that year it was awarded to Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, and afterwards Ngũgĩ was reported as saying that he was less disappointed than the photographers who had gathered outside his home: “I was the one who was consoling them!”

Ngũgĩ’s 2016 short story The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright became “the single most translated short story in the history of African writing”, now with versions in more than 100 languages. Originally written in Gikuyu (as “Ituĩka Rĩa Mũrũngarũ: Kana Kĩrĩa Gĩtũmaga Andũ Mathiĩ Marũngiĩ”), with an English translation by the author himself, alongside translations into numerous African languages, it was released by the Jalada Africa Trust, a Pan-African writers’ collective, in its inaugural Translation Issue, starting a project that aimed to translate each story into 2,000 African languages. In 2019, The Upright Revolution, Or Why Humans Walk Upright, illustrated by Sunandini Banerjee, was published by Seagull Books.

Ngũgĩ’s book The Perfect Nine, originally written and published in Gikuyu as Kenda Muiyuru: Rugano Rwa Gikuyu na Mumbi (2019), was translated into English by Ngũgĩ for its 2020 publication, and is a reimagining in epic poetry of his people’s origin story. It was described by the Los Angeles Times as “a quest novel-in-verse that explores folklore, myth and allegory through a decidedly feminist and pan-African lens.” The review in World Literature Today said:

“Ngũgĩ crafts a beautiful retelling of the Gĩkũyũ myth that emphasizes the noble pursuit of beauty, the necessity of personal courage, the importance of filial piety, and a sense of the Giver Supreme – a being who represents divinity, and unity, across world religions. All these things coalesce into dynamic verse to make The Perfect Nine a story of miracles and perseverance; a chronicle of modernity and myth; a meditation on beginnings and endings; and a palimpsest of ancient and contemporary memory, as Ngũgĩ overlays the Perfect Nine’s feminine power onto the origin myth of the Gĩkũyũ people of Kenya in a moving rendition of the epic form.”

Fiona Sampson writing in The Guardian concluded that The Perfect Nine is “a beautiful work of integration that not only refuses distinctions between ‘high art’ and traditional storytelling, but supplies that all-too rare human necessity: the sense that life has meaning.”

In March 2021, The Perfect Nine became the first work written in an indigenous African language to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize, with Ngũgĩ becoming the first nominee as both the author and translator of the book.

When asked in 2023 whether Kenyan English or Nigerian English were now local languages, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o responded: “It’s like the enslaved being happy that theirs is a local version of enslavement. English is not an African language. French is not. Spanish is not. Kenyan or Nigerian English is nonsense. That’s an example of normalised abnormality. The colonised trying to claim the coloniser’s language is a sign of the success of enslavement.” In 2025, he commented “In Kenya, even today, we have children and their parents who cannot speak their mother tongues… They are very happy when they speak English and even happier when their children don’t know their mother tongue. That’s why I call it mental colonization.” He also commented that he had no issue speaking English, but that “I don’t want it to be my primary language… if you know all the languages of the world, and you don’t know your mother tongue, that’s enslavement, mental enslavement. But if you know your mother tongue, and add other languages, that is empowerment.”

Ngũgĩ’s novel interweaves various storylines set during Kenya’s state of emergency under British colonial rule. Many young men are accused of fighting for the Mau Mau, arrested, and put in concentration camps in appalling conditions. Gikonyo, one of the central characters detained in the novel, is from the fictional Thabai Ridge, which is rendered in the book with a tremendous sense of local texture in terms of the shifting inter-generational relationships between young and old, the mutual attraction, the flirting and the reputational quests of young males and females, the community’s response to the newly arrived iron snake (the train) that creates a contrasting rhythm between predominant rurality and the incipient signs of urbanism, and of course, the people’s growing resentment at the colonial control of their beloved Ridge and of Kenya in general. During his six years of detention, Gikonyo is sustained by thoughts of Mumbi, his beautiful wife whom he has had to leave at home. Memories of her define the very basis of both hope and resistance and so it is with great expectation, after he is finally released from the concentration camp, that he undertakes the miles-long walk back home. The changing landscape of his walk through forest, on pavements and roads is carefully detailed by the narrator, and as he approaches his homestead, we remain with him in anticipation of the meeting with Mumbi. As we are told: “Walking towards it, Gikonyo wondered what he would do when he stood face to face with Mumbi. Doubt followed excitement; what if Mumbi was at the river or the shops when he arrived. Could he possibly wait for another hour or two before he could see her?” The moment when he sets eyes on her is however nothing like he expected. Rather, it represents a complete defeat of all his great expectations and a major reversal of emotional fortunes. This is what happens: “Actually, he almost hit her at the door. She looked at him for a second or two, gave an involuntary cry, almost hoarse, and with her mouth still parted, moved back a step as if to let him in. Gikonyo saw a child securely strapped on her back. His raised arms remained frozen in the air. Then they slowly slumped back to his sides. A lump blocked his throat.” He finally enters the hut at the prompting of his mother Wangari to sit and take stock of his surroundings and what it means that Mumbi has had a child with Karanja, his friend and rival for her attention when they were younger. His mother tries to assuage the obvious turmoil in her son’s eyes by saying “These things happen.” To which he replies, simply: “I’m tired, Mother. I have come a long way and I want to sleep.” The scene of Gikonyo’s arrival describes an arc of tremulousness, from the earlier anticipation, to the near-bumping into Mumbi at the doorway, to the almost-blinding sight of a child on her back that is not his, to his forlorn gesture of first raising his arms and then letting them slump back to his sides. I suddenly sprang bolt upright on my bed as if jerked up by a force beyond me and dropped the book. My heart beat fast and I was almost in tears. I set off on a long walk on campus to process what I had just read. Ngugi had that power to rouse the reader, unsettle him, and set him in motion. He changed utterly what it meant for me to read, and he had the same effect on many.

Across the continent, Ngūgī Wa Thiong’o was respected by peers and readers alike, alongside Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka, in the process forming Africa’s successful first generation of modern literature. A frequent Nobel candidate, Ngūgī’s peculiarities genius lay in the closely textured models of Kenyan Life he created, drawing on his native origins, where oppressive regimes, such as the Mau Mau, shaped his early years and those of millions across the country, influencing several-if not every- aspect of everyday life.

Such a visceral reaction to a scene from literature does not come upon me often. Beside this scene from A Grain of Wheat I can also remember the one at the end of Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, when after Okonkwo’s machete falls to behead the district commissioner’s messenger, the crowd of Umuofians behind him break into tumult rather than action and he hears them asking, “Why did he do it?” At that moment Okonkwo represents an epistemological enigma to his people and is no longer the renowned warrior we have come to see him as for the previous hundred plus pages of the novel. Then there is the moment in F. Scott’s Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby when Gatsby first kisses Daisy under the night sky and suddenly experiences all of the planets in the sky as somehow being elementally aligned in that precise moment. Then there is the moment in Toni Morrison’s Beloved when Paul D shows Sethe the newspaper with the drawing of her face in it when she was jailed for slicing her daughter’s throat. Her answer to his implied question is not a yes or no, but rather an inventory of the maternal acts she has performed for her children since they were all little and at the mercy of slavery. The implication is that even the act of killing her daughter is a gesture of supreme love. I could name a few more such scenes, but what they all share for me is the combination of ambivalence, doubt, and strong emotion to suggest something like a discombobulation of the self and its loss of biographical integrity for the individual character. It takes a very masterful writer to capture such moments in a way that renders visible simultaneously their authenticity and the tenderness of human vulnerability. Ngũgĩ was definitely one of such great writers, not just in African Literature, but in World Literature in general.

There are some who argue that Ngũgĩ could never have won the Nobel Prize because of his political stance, especially with his essays in the highly influential and much-lauded Decolonizing the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986). I think of the matter a bit differently. After the early work – Weep Not, Child (1964), A River Between (1965) and A Grain of Wheat (1967) – his writings took a definitive turn toward forms of socialist realism and they became more strident and message-driven. Petals of Blood (1977) was designed to illustrate the rise of rural class consciousness in opposition to the bourgeois political elites in Nairobi. Devil on the Cross (1980), first written entirely in his native Gĩkũyũ, was a political allegory of the crisis in Kenya, and Wizard of the Crow (2006), also written originally in Gĩkũyũ, is set in a fictional autocratic regime and is essentially satirical and didactic. The point to note, perhaps, is that the characters in his novels in the socialist realist phase no longer expressed the tremulous emotional uncertainty that we find in A Grain of Wheat. Rather, the key protagonists emerge as clear-sighted heroes set against oppressors of various kinds. The later Ngũgĩ also intended to rouse readers, and even though they might read these works comfortably in bed, yet for me I could not respond to the characters and situations in the later novels with all the deep human feeling with which I had responded to Gikonyo. There was, I think, a certain deformation in Ngũgĩ’s writing, even if its inspiration was easily understandable: he had become more and more impatient with the state of Kenya, the land he had been exiled from for over 40 years, and with oppression in the rest of the world. This anger impacted the fictional worlds that he represented so that his work came to require a form of urgent assent to a set of propositions that did not permit either contradiction or nuance. This was very far from the remarkably human tone of the earlier novels. Ngũgĩ was a committed Fanonian Marxist for much of his life and increasingly deployed his literary works as representational illustrations of his ideology. I think that it was this, more than anything else, that blocked him from winning the Nobel Prize for Literature. If his brand of political satire prevented him from winning the Prize, he was not alone. Has the Nobel Prize for Literature ever been awarded to a satirist in its entire history?

However, Ngūgī’s works wasn’t to be be defined purely by the masterful translation of social political materials. As his great works demonstrated, he rendered the panoramic with impressive intimacy, even in details, the delicate matters of sentences, the wise man’s hands showed, flavored with far-reaching influences. Consider this exerpts from his 1964-published debut novel, WEEP, NOT A CHILD. “They moved together, so as not to be caught by the darkness. A bird cried. And then Another. And these two, A boy and a girl, went forward, each lost in his world, for a time oblivious of the bigger darkness over the whole land,”

James Ngūgī’s, Decolonizing the Minds Language. Ngūgī’s private life was mired in controversy, as his son Mūkoma Wa Ngūgī once shared that he used to “physically abuse” his mother, Nyambura. “Some of my earliest memories are of me going to visit her at my grandmother’s, where she would seek refuge.”

The subject of an excellent essay on Brittle Paper, the report garnered considerable attention, and it remained a significant weight on the writer, as he never denied the claims until his death.

“To many, Ngūgī Wa Thiong’o means many things,” Nairobi-based poet and culture journalist Frank Njugi. “But to me, a kikuyi kid whose English barely stretched beyond the simple words when I first opened WEEP NOT, CHILD, his work was a revelation. It bridged the gap between the stories my Guka (Grandfather) wept through in a village in Nyandarau(during his eight years in colonial prison) and my understanding. It was like turning inherited pain into clarity. And when I saw the protagonist named “Njoroge”, my family name, it felt like literature had finally come home to me,”

Ngūgī’s work would reveal what Njugi called the “fragile architecture of identity” and provide conceptual background to his own interests as a writer, with over five decades shared between their era, which is as far-reaching an influence as any creative would hope for. “By the time I recognized this as my vocation,” Njugi says, “I had already absorbed the conviction that the most honest use of this craft is to write from the well of lived experience, both personal and inherited, to give form to the history inscribed on the skin- the history carried in your skin, your body, and the long journey etched in every scar and blemish on it.”

Ngũgĩ’s work was heavily steeped in biblical imagery and the Bible must be considered a primary intertext of all his writings. Petals of Blood is charged with both direct and indirect biblical quotations and references, with the Christian church and its attendant education system as frequent targets of attack. Taking a cue from Ngũgĩ’s own readings of the Bible, we will be forgiven if we interpret some of the more painful events in his life as akin to stations of the cross. In 1976, Ngũgĩ helped to establish the Kamiriithu Community Education and Cultural Centre, whose main focus was the organization of public theatre. The play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), co-written with Ngũgĩ wa Mirii and covering the themes of poverty, class struggle, and other related themes and published in the same year as Petals of Blood attracted the malevolent ire of the Kenyan government more than the novel did. The then Vice-President and later President Daniel arap Moi ordered his arrest and he was detained without trial in Kamiti Maximum Security Prison for a year. On leaving prison they refused to reinstate him to his position in the Department of English at Nairobi University. Conditions became so dangerous that he and his family had to move into exile in 1978, first to the UK and then to the United States. It was while in prison that he took the decision to stop writing any of his works in English but to do so only in Gĩkũyũ and to have them translated afterward. This was a watershed decision on his part that garnered him a lot of admirers all over the world and also not a few detractors. Detained, his prison diary, was published in 1981. It provides detailed descriptions of the woes and tribulations he and other political prisoners were put under but also testifies to his sheer hardiness and courage. Like Wole Soyinka’s The Man Died, it is considered a classic of the genre of prison writing in African literature.

For writer and critique Chiedoziem Chukwudera, the towering influence of Ngūgī’s work was “the advocacy for a better society”,he says “He showed the ability to truly educate the African reader of who they are and their place in the history. His early books, especially WEEP NOT, CHILD, and [Buchi Emecheta’s] Second Class Citizen, encouraged me as a writer to start writing with what I had. It was such a powerful story, even though it did not have the most profound structure. The book that had a better structure was “A Grain of Wheat”.

Chukwudera, the director of the Umuofia Arts and Books Festival, held annually in Eastern Nigeria,finds in that taut narrative the achievement of reflecting dramatic tenderness that seem to go beyond the page. Ngūgī says, he says, “was one of the male writers of his generation who wrote female characters the best, and he was able to handle tenderness in a character”.

Ngũgĩ took up a Visiting Professorship at Yale from 1989-1992 and then from 1992 became Professor of Comparative Literature and Performance Studies at NYU, holding the Erich Maria Remarque Chair. In 2002 he moved to the University of Irvine in California to take up the position of Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature and inaugural director of the International Center for Writing and Translation at the University of Irvine. These professional developments seem to have somehow obviated the pain of his and his family’s exile, but given how heavily steeped all his novels were in the natural environment of his homeland, it is also clear that this was never a straightforward matter.

Family

Four of his children are also published authors: Tee Ngũgĩ, Mũkoma wa Ngũgĩ, Nducu wa Ngũgĩ, and Wanjikũ wa Ngũgĩ. In March 2024, Mũkoma posted on Twitter that his father had physically abused his mother, now deceased. Ngũgĩ did not acknowledge the accusation.

The next traumatic setback came on his visit to Kenya in 2004 as part of a one-month tour of East Africa, some two years after the passing of his nemesis Daniel arap Moi. Despite his residing in a high-security apartment, thugs still managed to break into the place, assault him and rape his wife in front of him. The whole world was utterly sickened at these events, and there has been much speculation since then as to whether they were politically orchestrated or the work of vengeful family members. Whatever the truth we can assume that this homecoming after nearly twenty years, like Gikonyo’s, must have turned the very idea of his homeland to ashes.

On March 12, 2024 Mukoma wa Ngũgĩ, Ngũgĩ’s second child and himself a writer, posted on X (formerly known as Twitter) that his father had been physically abusive to Mukoma’s mother Nyambura, Ngũgĩ’s first wife. This was a heartrending revelation to many observers and took me back personally to many such scenes in my own childhood and in that of my friends. My first thoughts went to Nyambura. What must it have been like to see the intelligent and sensitive writer switch, perhaps under minor provocation, to unrestrained violence toward her? The gasps, the bewilderment, the tears, and the confusion? The sheer terror when violence was further threatened and happened again and again? Then my thoughts went to Mukoma. What must it have felt like bearing witness as a child to this violence from his father against his mother? He clearly adores his father, and it is no accident that he himself has become a writer and also a spokesperson for equity and justice whenever the opportunity has presented itself. But what long turmoil must he have endured to declare this terrible fact to the world on the social media platform, the home of sceptics and trolls of all kinds? Was it because it was of a recognition that it would be impossible to get his illustrious father to acknowledge some of the contradictions embedded in his own life as writer, father, husband, and African of that generation? Or simply as a father himself, the very loss of faith in the very principle of fatherhood? And what of Ngũgĩ himself? What must it have felt like to see his son disclose in public what may have long been the source of private angry disputes within the family? How did it feel to experience this while newly divorced from his second wife (the rape survivor twenty years earlier in Nairobi), and living alone and battling kidney failure and being on dialysis? What must he have felt when he contemplated the resentment of another writer, no other than his own son? We do not know how father and son dealt with this most delicate and painful matter and everything that has followed afterward in the public debate has been speculation, as are the words I have just written. Literature, however, can help us imagine what human contradiction and human suffering are like.

Illness and death

In 1995, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was diagnosed with prostate cancer and was told he had three months to live; nevertheless, he recovered. In 2019, he had triple bypass heart surgery, and around this time, began to struggle with kidney failure. He died in Buford, Georgia, United States on 28 May 2025, at the age of 87. At the time of his death, Ngũgĩ was reportedly receiving kidney dialysis treatments, but his immediate cause of death was not announced.

After Ngũgĩ’s death, Western news outlets highlighted his efforts to fight colonialism and other social critiques. Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka, fellow Kenyan writer David Gian Maillu, Kenyan President William Ruto, and politician Raila Odinga paid tribute to Ngũgĩ following his death.

This definitely speaks to the multidimensional greatness of Ngūgī’s that every reader will almost certainly have different books of his as their favorite. Personally, I became most interested in his writing after reading Wizard of the Crow, a fantasy-blended narrative that revealed the farce inherent in Afrcan societies and political systems. A thrilling tour de France, writer such as Nnedi Okorafor and Aminatta Forna have mentioned it as a sterling offering, definitely a late-career gift from one of Africa’s greatest wordsmiths.

Ngugi’s memoir of childhood, Dreams in a Time of War, opens with his experience of reading T.S. Eliot, a reading which brought back to him his personal experience. In contemplating Ngũgĩ the man the haunting words from T.S. Eliot’s “Marina” come to mind:

What seas what shores what granite islands towards my timbers

And woodthrush calling through the fog

My daughter.

Eliot’s lines are inspired by the Jacobean play Pericles, Prince of Tyre, that was partially attributed to Shakespeare and provides the inspiration for his own poem, named for Pericles’s presumed dead daughter Marina. The lines imagine Pericles’s encounter with his adult daughter almost as if through a dreamlike sequence. The lines capture something of this oneiric reality, and is notable for its mixture of visual cues, “fog,” auditory cues, “the woodthrush calling,” and the vague admixture of the sense of peril, “granite islands toward my timbers,” and the relief of seeing again the long-lost daughter through the mist. I think of these lines now because they evoke something of the fragility of the bond between parents and their children that always ebbs and flows and frequently threatens to evaporate even when being grasped in celebration.

While it is clear that Ngũgĩ wa Thiongo had many flaws, it is also safe to say that he was uncompromising in the pursuit of what he saw as the truth and that he sought to deploy his writing as a penpoint in the war against oppression and ignorance of all kinds. His life shows all the markings of one we must be glad to hail as an African ancestor. Like Gikonyo he walked a very long way and deserves to Rest in Perfect Peace.

And so Ngūgī goes home at the age of 87. His words and ideas will live on. The man behind the words has done so much living himself, and we are the better of it living through the Legacy of appreciation the Demeanor and Literary appreciation of the great Ngūgī Wa Thiong’o.

IN SUMMARY

“I have come a long way, and I want to sleep”: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (5 January 1938-28 May 2025)

He earned his Bachelor’s degree in Uganda, at the Makerere University College, and a master’s degree in Leeds, England. It was at Leeds that he met the late Professor Ime Ikiddeh, who helped shape, his literary beliefs, and subsequently, the need to embrace the local languages, as a means of literary communication. He returned to Kenya in 1967, becoming a lecturer in English Literature at the University of Nairobi.

In 1967, while lecturing at the University of Nairobi’s English Department, he pushed for it to be replaced by a literature department that would cover not just English Literature, but also the new African and world literature.

Eventually, he became frustrated that the main audience for his criticisms was the English-speaking middle classes, rather than the poor peasants and workers he looked to for a change in the society.

In the 70s, he started writing in his mother tongue, Gikuyu, helping the peasants to produce the now-famous play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), which he co-wrote with Ngugi wa Mirii.

His arrest and detention (without charge and in a maximum security prison) came only after he began to write in Gikuyu instead of English, thereby reaching a far greater number of ordinary Kenyans, a development that the authorities found threatening. While in detention, he wrote his first novel in Gikuyu, Devil on the cross, on toilet paper. He has written other novels in his mother tongue such as ‘Matigari’ and ‘Wizard of the Crow’.

In 1977, Ngugi was imprisoned for a year, without trial. After an international campaign led by Amnesty International led to his release, the Moi Dictatorship banned him from taking jobs at the country’s colleges and universities. Ngugi’s works were also removed from all educational institutions. He was thus forced into exile in Britain (1982-1989) and then in the United States (1989-till death).

Ngugi questioned the gulf between African intellectuals and their audience and resolved to write in his own tongue, Gikuyu.

He said, “The death of any language is the loss of knowledge contained in that language. The weakening of any language is the weakening of its knowledge-producing potential. It is a human loss. Each language, no matter how small, contains the best knowledge of its immediate environment: the plants and their properties, for instance. Language is the primary computer with a natural hard drive.”

Ngugi’s novels have been translated into over 30 languages. He often translated his works into English himself. He has held on to the vision that literature written in African languages such as Luo or Yoruba would be translated directly into other African languages without using English as an intermediary.

“That would allow our languages to communicate directly with each other,” he reasoned.

His numerous works include The Black Hermit (play), Weep Not Child, The River Between, Grain of Wheat, This Time Tomorrow (three plays, including the title play), The Reels, and The Wound in the Heart.

Pioneering Literary Work & Cultural Thought

- Novelist, Playwright, and Scholar: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was a pivotal figure in shaping African literature, with influential works like Weep Not, Child and The River Between, which explored the complexities of identity, colonialism, and social justice.

- Champion of Indigenous Languages: He championed writing in Gĩkũyũ and other African languages, asserting that “language is identity” and that liberation begins with speech. This was a direct challenge to the colonial imposition of European languages as an “instrument of conquest”.

- Themes of Liberation: His writing consistently explored the role of culture as a source of historical memory and a weapon against oppressive systems.

Activism and Political Dissent

- A Voice Against Oppression: Ngũgĩ was a fearless voice against colonial systems and post-independence authoritarian regimes, which led to his imprisonment in 1977 and forced exile.

- Literary as a Tool for Liberation: He viewed literature and storytelling as crucial tools for cultural and intellectual decolonization, empowering communities to name and tame their environment and reclaim their history.

Enduring Legacy and Inspiration

- A Literary Titan: Ngũgĩ’s legacy is cemented through his influential body of work and his courageous intellectual stance, making him a cultural icon across Africa and the diaspora.

- Inspiring Future Generations: His conviction that language is identity continues to inspire new generations of writers and thinkers to write, speak, and dream in their own languages, fostering a continued fight for cultural freedom.

- Decolonizing the Mind: His seminal work, Decolonising the Mind (1986), remains a foundational text for those seeking to understand and dismantle the lasting effects of colonialism on language and thought.