1)“DISGRACE” by J.M. COETZEE, 1999

J.M. Coetzee’s “Disgrace” is about a lot of things, but at its heart it is an anatomy of racial hierarchy change in contemporary South Africa. The book is also about the condition of the human experience at the end of the Apartheid regime. Published in 1999, this is Coetzee’s second book where characters are compelled to explore the intricate complexity of humanity after he published “Life & Times of Michael K” in 1983.

J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace was awarded the 1999 Booker Prize. The novel opens with an almost banal story of a fifty-two-year-old university professor from Cape Town, David Lurie, who after his divorce settles into a life of routine, devoting his time to his courses and to his weekly appointments with a prostitute. This ‘perfect’ schedule in a well-ordered life is upset by an affair with one of his students, Melanie Isaacs. The ensuing scandal leads to his dismissal. David Lurie is transformed into a pariah and leaves for the Eastern Cape to visit his daughter Lucy whose farm has been burgled by people who raped her. In this novel, J.M. Coetzee seems to depart from the complex narrative structures of some of his previous works such as Dusklands or Life & Times of Michael K. Yet the limpidity, lyricism and simplicity of plot in Coetzee’s latest work are only a surface appearance.

The Story revolves around the life of “twice-divorced” communications, Professor David Lurie as he struggles with the societal restrictions placed on his serial endeavors in a country still reeling from the effects of the apartheid regime. After he is fired from his job at Cape Town Technical University because of sexual harassment case opened against him, he has to go live with his daughter. David is thrust into a rural world filled with crime, poverty and rape, and must salvage whatever is left of his daughter against the backdrop of violent strikes in the Salem area of Eastern Cape.

The diegesis contains the complex ingredients of postcolonial writing where intertextuality enriches the literary discourse. David Lurie teaches the Romantic poets and has published works on Faust and Wordsworth. There are echoes of the chorus in Oedipus, of the first cantos in Don Juan and allusions to Lucifer and Cain, to Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, to Emile Zola’s J’accuse, to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, to Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, to the character of Casanova and to Victor Hugo’s poem on being a grandfather. Furthermore the text alludes to modern post-apartheid South African drama with the play Sunset on the Globe Salon. Throughout the novel, the reader is informed about David Lurie’s attempts to do some creative work in music based on Byron in Italy.

The mention of the Romantic poets and of Don Juan at the beginning of the novel stresses the period when David Lurie lives in harmony with himself, having reached maturity and wisdom while at the same time having proved to himself that he is still sexually attractive to the young Melanie Isaacs. Madame Bovary is mentioned twice: first, when David tries to find out more about Soraya, his Indian mistress, who is married and becomes a prostitute in the afternoon, thus leading a double life like Madame Bovary; secondly, when he makes love to the middle-aged, parochial married woman Bev Shaw, who thus breaks the monotony of her dull provincial life in Salem. Her name, Bev, is connected to Bovary, a clearly deliberate choice. Zola’s J’Accuse is evoked when Melanie Isaacs decides to lodge an official complaint against David Lurie under the pressure of her boyfriend and relatives. At the University of Cape Town, Melanie Isaacs reads Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, an indication that the study of race issues witnesses to the open-mindedness in South African universities. The reference to the rehearsal of the play Sunset at the Globe Salon reflects the new political reality where ‘all the coarse old prejudices are brought into the light of day and washed away in gales of laughter’. A learned person, David Lurie thinks of Victor Hugo, ‘the poet of grand-fatherhood’, when he starts accepting the idea of becoming the grandfather of a child conceived during his daughter’s rape by the black burglars. So the way these literary titles and names become part of the story implies a cultural and ideological ‘overcoding’ of the text, to use Wolfgang Karrer’s term. More than any other White South African Writer, J.M. Coetzee seems to need these ‘models of coherence’,to construct his text.

The symbolic impact of the overcoded characters’ experiences is powerful, especially in the post-apartheid context of the novel. David Lurie’s relationship with Melanie Isaacs, who could be his daughter, as well as his relationship with Lucy, his own daughter, embody his political pre-occupations. In Beginnings: Intention and Method, Edward Said shows the importance of ‘beginnings’ in novels, arguing that they provide the key to an appropriate reading and decoding of the text. At the opening of Disgrace, the reference to the chorus of Oedipus operates as a ‘mise en abyme’ for the whole story. The omniscient narrator reports David Lurie’s thoughts: ‘He has not forgotten the last chorus of Oedipus: Call no man happy until he is dead’. David Lurie’s apparently harmonious life is going to be disrupted through his specific relations with the two ‘daughters’. The affair with Melanie becomes a paradigm for South Africa, a country sure of itself with its apartheid laws before 1991, but shaken after their abolition. Beyond David Lurie’s mid-life crisis, his relationship with Melanie becomes a strong allegory for the old and the new, the past and the present. There are signs which sustain this interpretation as when David thinks about changing Melanie’s name to ‘Melàni, the dark one’. At this point Melanie becomes a symbol for a difficult period of transition. In another episode, David in class explains the term ‘usurp’ quoted from Wordsworth’s The Prelude, which hints at their illegal/illicit affair. Wordsworth’s poem evokes the guilt which pervades the novel. David’s conscious reference to South Africa while discussing a poem set in the Alps stresses his wish to link the two geographical settings through European literature: ‘We don’t have the Alps in this country, but we have the Drakensberg, or on a smaller scale, Table Mountain, which we climb in the wake of the poets, hoping for one of those revelatory, Wordsworthian moments we have all heard about’. Another time, the first line of one of Byron’s poems which he discusses with his students suggests a secret wish for the emergence of a new world for the Whites: ‘He stood a stranger in this breathing world’. The whites must adopt a new attitude if they do not want ‘to be condemned to solitude’ like Byron facing Lucifer.

Even though Melanie consents to making love with David Lurie, more out of duty towards the professor than out of true love, incestuous undertones mar their relation. One of their meetings appears as a rape scene as the narrator reports: ‘A huge mistake, he has no doubt, Melanie is trying to cleanse herself of it, of him; he sees her running a bath, stepping into the water, eyes closed like a sleepwalker’s’. Melanie, a symbol of South Africa, is raped by a political system which has kept the best for the white community. A committee entitled ‘Women Against Rape, WAR,’ accuses David of being part of a ‘long history of exploitation’, sending him leaflets saying ‘your days are over, Casanova.’ After Melanie’s revolt, David Lurie is seen by the Board of Administration of the university as ‘a worm in the apple’ , a ‘viper’, a disgraced disciple of Wordsworth’. Melanie Klein shows how rape can physically injure the body and perturb the personality of the victim, who has to learn to free herself from the father figure, from the Oedipus complex. Melanie Isaacs goes through a similar process, moving away from David Lurie, abandoning her literary classes, developing fear and sadness, learning slowly to live with people of her own age, probably a process South Africa has to go through to move away from the apartheid system.

Ironically David Lurie, who is accused of ‘abuse’ and rape in Cape Town, witnesses in Eastern Cape the rape of his daughter, who has become a solid countrywoman, a ‘boervrou’, by three black men. This provokes a confrontation between David Lurie and the other South Africa, that of the farmers and the land. The white characters are faced with a history they have created. Coetzee’s story is certainly inspired by the harsh reality of South Africa today where rape has become one of the major forms of criminality. Yet Lucy’s reaction differs from what studies show in most cases of rape. Generally, women are ashamed to speak about the assault because they feel guilty and fear being thought to have encouraged the rape, precisely because they are women. Here, only the burglary is reported to the police for insurance purposes. For complex reasons, Lucy does not want the police to know about the rape:

‘As far as I am concerned, what happened to me is a purely private matter. In another time, in another place it might be held to be a public matter. But in this place, at this time, it is not. It is my business, mine alone.’

‘This place being what?’

‘This place being South Africa’.

The bewildered father does not comprehend the logic of such an attitude as his prejudices concerning the division of the world into ‘civilised’ and ‘uncivilised’ parts come back to the surface. He is still full of Conradian prejudices when he thinks that ‘Italian and French will not save him here in darkest Africa’; he also refers to Madagascar as ‘darkest Africa,’ in contrast to Cape Town, the white, the ‘civilised’. He believes he is still in a world of ‘savages’, a term he uses deliberately when he meets one of the three aggressors, ironically named Pollux’: ‘That is what it is like to be a savage!’. He does not feel guilty for the past history of South Africa, even if he admits that his ancestors were not always right:

Lucy, I plead with you! You want to make up for the wrongs of the past, but this is not the way to do it. If you fail to stand up for yourself at this moment, you will never be able to hold your head up again. You may as well pack your bags and leave.

Lucy’s secret becomes ‘his disgrace’, his failure as a father to convince her to report the rape to the police and to stand up for her rights in this new era, to ensure the survival of a whole community.

Even though Lucy is shocked by the rape, especially since she is a lesbian, she shows far more distress over the personal hatred the three black men expressed during their shameful act. Here it is David Lurie who reassures his daughter by putting the event into its psychological context. He explains the rapists’ attitude as being a consequence of ‘History’: ‘It was history speaking through them. A history of wrong. Think of it that way, if it helps. It may have seemed personal, but it wasn’t. It came down from the ancestors’. Lucy’s analysis of the event gives meaning to her decision: ‘They see me as owing something. They see themselves as debt collectors, tax collectors. Why should I be allowed to live here without paying?’, the father explains, but does not forgive, which is not the case with his daughter. From that point on, the gap between them widens. He thinks that she should leave Eastern Cape for good and South Africa for a while to go to Holland ‘until things have improved in this country’. Yet Lucy decides to stay. Their difficult, but close, relationship at all levels goes back to her childhood, which justifies to a certain extent her rejection of men. The burglars’ assault on her helps her to break free from her Oedipus complex: ‘I cannot be a child forever. You cannot be a father forever. I know you mean well, but you are not the guide I need, not at this time’. This break conveys the idea that Lucy’s behaviour becomes a paradigm for the young generation’s understanding between black and white in South Africa.

Lucy rejects her father’s advice to have an abortion. In African literature, pregnancy has often been a sign of hope for the future as we see in Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s A Grain of Wheat and in Ayi Kwei Armah’s Osiris Rising. Lucy declares: ‘I am determined to be a good mother. A good mother and a good person’. Despite the tragedy, Lucy shows that concessions and compromises have to be made because the different communities are bound to live together, a fact which David Lurie admits at the end of the novel when he sees his pregnant daughter farming, ‘looking suddenly the picture of health’, remembering that the baby she is bearing is of mixed parenthood or, as the future grandfather says, ‘a child of this earth’. Coetzee pleads here for biological hybridity in order to save the country, a ‘projected ‘rainbow country’, to use Dominic Head’s expression.

Disgrace also addresses the question of land, a major issue in Southern Africa. Interestingly, it anticipates on the current conflict between black and white Zimbabweans. In South Africa, the abolition of apartheid has brought freedom for the black people to own land if they can afford it. In Disgrace, Petrus, Lucy’s black co-owner, embodies the new world they live in. Because of decades of frustration, Petrus’ dream is to own as much land as he can. Yet much of it still belongs to the whites. David Lurie suspects Petrus of having some connection with the rapists whose acts are part of a strategy to unsettle white farmers. David Lurie knows that ‘Petrus would like to take over Lucy’s land to have Ettinger’s too, or enough of it to run a herd on’. Petrus agrees to be a farm manager for Lucy if she decides to have a break. The novel clearly shows how, with the many burglaries, the country is not safe anymore: ‘Too many people, too few things’. This situation breeds fear, so the whites buy guns to protect themselves, like the farmer Ettinger who explains how he survives: ‘I never go anywhere without my Beretta. The best is, you save yourself, because the police are not going to save you, not any more, you can be sure’. In this context, Lucy’s decision to return to the farm is remarkable. As Petrus says, ‘she is a forward-looking lady, not backward-looking’.

Though strange, the relationship between Lucy and Petrus witnesses to a desire to live together. Through a marriage of convenience, he promises to protect her, and to make her part of the people, of the land. Lucy explains to her sceptical father: ‘He is offering an alliance, a deal. I contribute the land, in return for which I am allowed to creep in under his wing’. Her acceptance sounds humiliating but in the context of South Africa, Lucy’s attitude becomes a sign of wisdom, a way of facing up to the nation’s history:

‘Perhaps that is a good point to start from again. Perhaps that is what I must learn to accept. To start at ground level. With nothing. No cards, no weapons, no property, no rights, no dignity.’

‘Like a dog.’

‘Yes, like a dog.’

The experience is harsh for the whites, after so many years of supremacy. As Coetzee says in a recent interview, ‘at the deepest level, many still haven’t understood or accepted that life cannot go on as it did before.’ Nevertheless the scene in which David Lurie and Petrus watch a football game which ‘ends scoreless’ symbolizes a new start in South Africa in which there is no winner and no loser.

In Disgrace, the absence of Black South African culture as such reveals a lapse at the symbolic level even if black characters such as Petrus and Pollux are central in the psyche of the white characters. Such an absence contradicts to a certain extent the obvious desire for a harmonious world expressed by the clear-headed Lucy whose name means ‘light’. Such an idea is also endorsed by David Lurie whose name refers to the biblical story of David and Goliath, David recognizing Goliath’s rights. David Lurie, Melanie Isaacs and Lucy represent three faces of white South Africa. They express contradictory views and show signs of disarray in the face of the new social and political order which remains complex and brutal despite the post-apartheid government’s desire to be more forward looking. Coetzee’s narrative strives to untie the knots of history. The apparently simple and linear plot which expresses the author’s desire for law and order is filled with his questionings, guilt, anxiety and bewilderment. Disgrace is postmodern since it ‘stresses the tensions that exist between the pastness and absence of the past and the presentness and presence of the present,’ bearing in mind that the whites in South Africa are still in a state of shock’, as J.M. Coetzee comments. Through literature, Coetzee tries to reconstruct a new psyche in South Africa like Desmond Tutu who was given a mission in 1995 by Nelson Mandela ‘to reconcile the whole country, to alleviate the bitterness between the communities… to carry the dream of a unified Nation.’ This novel should speak to South Africans about ‘their present, their past and their possible futures.’

Although race is a recurring issue throughout the book, it focuses more on the themes of poverty, crime, blood-shed, homosexuality and the AIDS epidemic. The book has gained praise from international audiences for showing the true extent of the damage apartheid had on the South African people, while also drawing its share of criticism, particularly from the ANC government, for showing South Africa in “too pessimistic” a light.

2) “FOOLS AND OTHER STORIES” by NJABULO NDEBELE, 1983

“Food and Other Stories” is a collection of tales from the closing days of the apartheid regime in South Africa written by one of the Continent’s most powerful voices of cultural freedom, Njabulo Ndebele.

Set in black South African township of Charterson in the East Rand, the book deals with the formative experiences of growing up in Johannesburg township during the apartheid years.

The Test

For a long time, I wanted to write about the streets of my childhood, our games of summer and rain, my poverty and my perception of it. I have still not been able to pen down anything without it sounding like a chip on my shoulder I need to get rid of very quickly. But in Thoba’s story, in the African 1960s, about a boy stuck in sudden showers of rain while playing football with the children of his street, I saw the story of the 90’s kids, of underlying competitions between people and the social groups and circles it created. It reminded me that childhood is universal, and so is adolescence and the troubles that come with it. When you’re under 16, removing your shirt and chasing the winds like a horse is the most heroic thing to do. And sometimes, the shame that follows is worth it.

“Thoba envied these boys. They seemed to not have demanding mothers who issued endless orders, inspected chores given and doe, and sent their children on endless errands. Thoba smiled, savouring the thrill of being with them, and the joy of having followed the moment’s inclination to join them on the veranda.”

“Yes, indeed, Mpiyakhe was stealing glances at him too. But now that there were only the two of them, there really seemed no reason to quarrel.”

The Prophetess

Sometimes when I walk home at night and imagine all the dreadful things happening to me, I am scared. Not of those dreadful things, but what my parents will say to that. And when some dreadful things do happen to me, I keep them from my parents, knowing that they will be affected deeper than I, and I can carry social burdens they never thought possible.

The Prophetess brings the magic of ancient Africa and the hymns of yore to a small boy who has come with a bottle of water, so she may bless it and he may use the water to cure his ailing mother. He walks home scared, and in the darkness, drops the water. Filling the bottle with regular tap water, he returns home. He prays for the water to be blessed again, and the mother’s faith in the Prophetess is unwavering. Is belief enough to bring magic into our lives?

“And that’s our problem. We laugh at everything, just stopping short of seriousness.”

“You see, you should learn to say what you mean. Words, little man, are a gift from the Almighty, the Eternal Wisdom. He gave us all a little pinch of his mind and called on us to think. That is why it is folly to misuse words or not to know how to use them well.”

Uncle

The first two stories showed what revolution would mean to young kids — defying their parents, and lying to their mothers. Uncle is a transition story, where a small kid, whose uncle comes to stay with him, is introduced to ideas and events that happen beyond his immediate geography and awareness. His uncle is a trumpet-playing piper, who reads and learns new languages so that he may rebel but now without a cause. He plays the trumpet, picks a fight with street goons, and tells his nephew of the importance of fire and passion, history and language and of knowledge. And the story holds snippets of wisdom for mshana and the reader. He learns about desire and women, about the need for music. He doesn’t realise it yet, but little mshana learns that there are things in life more important than showing off your own uncle to your friends.

“This whole land, mshana, I have seen it all. I have given it music. You too must know what you can give it. So you must make a big map of the country, your own map. Put it on the wall. Each time you hear of a new place, put it on the map. Soon you will have a map full of places. And they will be your places. And it will be your own country. And then you must ask yourself: what can I give to all those places? And when you have found the answers, you will know why you want to visit those places.”

“I’m still their friend. But when two people say one thing and you, alone, say another, it begins to look as if they are right and you are wrong. And when they are friends it is worse because you want to be with them, because you are friends with them, but at the same time you want to do what you want to do. If I want to do what I want to do, I should do it and still be friends; and if they they want to do what they want to do, they should go and do it, and we shall meet tomorrow and still be friends.”

“Whether or not you go to school, you must find time to know. Then you can never be deceived. Once you know you can never be deceived. But when you know, never deceive.”

The Music of the Violin

A couple of weeks ago, I watched Sergei Polunin’s documentary ‘Dancer’, a fantastic insight into what the deadly combination of talent and hard work can do — it can make you wildly successful, but can also break your spirit. It left me wondering, how much of his childhood had Polunin lost because of his mom’s insistence on ballet.

The Music of the Violin is about a young African boy whose mother insists on his violin playing, a white man’s symbol, for which he is ridiculed by street boys and always turned into a spectacle for both willing and unwilling guests. It shows how parents can bring disaster upon their children — because they may say ‘Ignore the savages’ but it is you who has to go out there and listen to a big bully tell you that he wants to fuck your sister while you play music in the background.

And as for the children of all developing world, reeling under a double cultural consciousness, they will always be stuck — either they please the street and fit in, or please their parents at home and be ostracised.

Fools

In the ideologically most fascinating, powerful and comprehensive stories, Ndebele pitches an old teacher who had raped his student versus her brother, an idealist youth of a pure, all-consuming desire to rise above the lethargy of today, Zani. Zani could well be the product of the Uncle’s teaching to his mshana, and he is the man who lived with books so much, he forgot the people. The two meet for the first time at a train station and from there on, there begins a conflicted journey that includes rebellions, conformity, the Teacher’s confrontation of his own past, of his own self and Zani’s vision of the present and the future.

In the middle of this, is Zani’s lover Ntozakhe, his sister Mimi, the teacher’s wife Nosipho and the bonds of love, hate and the in-between that define their lives. The teacher reminds you of Humbert Humbert in places, but this character is far more tired of himself, conflicted within himself and is constantly trying to punish himself, deliberately landing in socially disastrous situations. It is the most surrealistic of stories, where visions and forms intermingle with real worries and real people.

“And you will learn, that you cannot put aside everything in the pursuit of your dreams.”

Ndebele’s prose is haunting, poetic, accurate and lyrical. It rings of something deep and true, a wisdom bestowed from the depths of the earth. The collection, with characters that occur in every story, is confined to a small geography but echoes the worries and truths of all civilisation. In these words you will find that time can stop, and that perhaps all of humanity lives the same moment again and again, repeatedly, without end, repeating mistakes, repeating its analyses, its actions, its rebellions but never quite moving forward. “Isn’t it what we have lost; the demanding formality of civilisation?”

Favourite Quote: (from Fools)

But I learnt one lesson out of all this. It is that we should have stuck to our science. You see, too much obsession with removing oppression in the political dimension, soon becomes itself a form of oppression. Especially if everybody is expected to demonstrate his concern somehow. And then mostly all it calls for is that you thrust an angry fist into the air. Somewhere along the line, I feel, the varied richness of life is lost sight of and so is the fact that every aspect of life, is it can be creatively indulged in, is the weapon of life itself against the greatest tyranny.”

The current Chancelor of the University of Johannesburg, Ndebele has always been adamant about African literature moving away from the all-too- easy narrative of poverty porn and the preoccupation with showing obvious oppression, but rather how and why people soldier on through the adversities and hardships.

Ndebele narrates township life’s with such a humorous subtlety you could overlook the varying copying mechanisms and survival tactics black people had to devise to survive under the rule of the apartheid regime just to enjoy how fun he makes township life seems.

The narratives concern the effects of the apartheid from those who enforce to those who suffer under its iron rule, like the title story about an Old dissipated school teacher and one of his former students who has become an activist. It details their vastly different but equally debilitating experiences with racism and highlights Ndebele’s deft ability to handle ordinary people’s lived experience.

It won him a much-deserved NOMA Award in 1984, the highest honor any author can attain on the Continent.

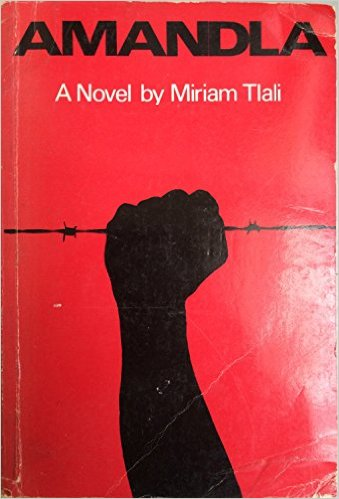

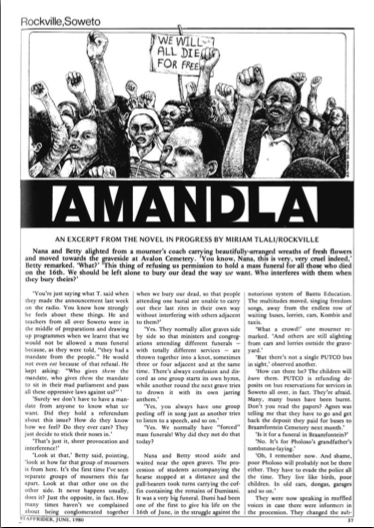

3) “AMANDLA” by Miriam Tlali, 1980

In 1975, Miriam Tlali became the first black woman in South Africa to publish a novel (“Muriel At Metropolitan”). “Amandla” was her second novel. Published in 1980, it focuses on the experience of a group of young student revolutionaries in Soweto during and after the 1976 Soweto Uprising.

South African novelist Miriam Tlali’s “Amandla” is one of a handful of Black Consciousness novels that renders in fiction the June 1976 Soweto uprising.

Published in 1980 by Ravan Press, it was only the second novel authored in English by a black woman to be published within the borders of apartheid South Africa (her 1975 debut, “Muriel at Metropolitan” was the first). Predictably, “Amandla” was banned upon publication.

South African novelist Miriam Tlali’s “Amandla” is one of a handful of Black Consciousness novels that renders in fiction the June 1976 Soweto uprising. Published in 1980 by Ravan Press, it was only the second novel authored in English by a black woman to be published within the borders of apartheid South Africa (her 1975 debut, “Muriel at Metropolitan” was the first). Predictably, “Amandla” was banned upon publication.

Amandla” offers a richly detailed fictional account of the 1976 Soweto uprising, when the township’s youth rose up against the decision to make Afrikaans compulsory as a medium of instruction in black schools. “Amandla” is written from the perspective of a number of young revolutionaries of the time.

Based on Tlali’s experience as a Soweto resident in 1976, the novel depicts the uprising and its aftermath. It vividly sketches the mechanics of the Black Consciousness ideology in the service of anti-apartheid activism. “Amandla” does so while teasing apart gender relations between men and women activists, and within the larger community.

It is one of four novels considered “Soweto novels”, works of fiction depicting the June 1976 uprising. The others are Mongane Serote’s “To Every Birth its Blood” (1981), Sipho Sepamla’s “A Ride on the Whirlwind” (1981) and Mbulelo Mzamane’s “The Children of Soweto” (1982).

These novels are heavily influenced by Black Consciousness ideology. They are also shaped by Steve Biko’s writings on a unified black populace that would decolonise itself from racist indoctrination.

However, “Amandla” departs from these novels in an unprecedented attentiveness to the gender politics of the day. It engages in the mimetic work of reflecting black gender relations in Soweto. The novel also constructs a new vision of black masculinity.

The Book offers a richly detailed fictional account of the 1976 Soweto uprising, when the township’s youth rose up against the decision to make Afrikaans compulsory as a medium of instruction in black schools. “Amandla” is written from the perspective of a number of young revolutionaries of the time.

Based on Tlali’s experience as a Soweto resident in 1976, the novel depicts the uprising and its aftermath. It vividly sketches the mechanics of the Black Consciousness ideology in the service of anti-apartheid activism. “Amandla” does so while teasing apart gender relations between men and women activists, and within the larger community.

It is one of four novels considered “Soweto novels”, works of fiction depicting the June 1976 uprising. The others are Mongane Serote’s “To Every Birth its Blood” (1981), Sipho Sepamla’s “A Ride on the Whirlwind” (1981) and Mbulelo Mzamane’s “The Children of Soweto” (1982).

These novels are heavily influenced by Black Consciousness ideology. They are also shaped by Steve Biko’s writings on a unified black populace that would decolonise itself from racist indoctrination.

However, “Amandla” departs from these novels in an unprecedented attentiveness to the gender politics of the day. It engages in the mimetic work of reflecting black gender relations in Soweto. The novel also constructs a new vision of black masculinity.

Why is/was it influential?

Tlali uses Black Consciousness discourse as a launching point for this vision of masculinity. The novel tracks the life of the student leader, Pholoso, and a range of minor characters.

The reader follows Pholoso as he becomes a leader of the youth. In this role he has conscientising sessions in the cellar of a church with young people active in the struggle. Here Tlali allows him long streams of dialogue. He outlines several position statements from the underground resistance movement on how society should be organised.

Relationships between black men and women is one area where he “instructs” the youth on ethical behaviour. In one scene, Pholoso addresses a room of 22 activists as “Ma-Gents”, making it clear that the room is filled with young men. Within this masculinised space, Pholoso articulates, among other things, a strong position on gender equality and relationships with women.

First, he addresses the absence of women from the “innermost core” of the underground movement this gathering represents. He attributes women’s absence to the high levels of sexual harassment to which women are subject whenever they move around Soweto.

Pholoso names this scourge of molestation as an impediment to women’s participation in political activity. He believes it should be countered through educating the public at large.

Critics such as Cecily Lockett and Kelwyn Sole have critiqued Pholoso’s centrality as a student leader. They have also scrutinised the masculine space wherein he operates as reifying women’s subservient positions within the anti-apartheid struggle. Margaret Miller makes the case that Pholoso’s utterances confirm the marginal role women seemingly played in the 1976 uprising in his “patronising and contradictory” speech.

What critiques such as Miller’s ignore are the reasons Tlali may have for recruiting a black man in the role of gender conscientising. He is equated with Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt, to disseminate a message of gender parity through the community.

In addressing the “Ma-Gents” on the sexual harassment, treatment and education of women, Pholoso advocates an oppositional black masculinity to counter dominant iterations of masculinity in Soweto. He exhorts the men to “go out and educate the people”. Pholoso is reliant on a ripple effect his message will have as it spreads out in concentric circles among the township’s men.

It is important to note that he is not addressing white men or women and their treatment of black women, but black men specifically. A black man himself, he holds black men as a group accountable for the safety, education and equitable treatment of women. He is gesturing to a time as yet unknown, in the future, when black subjects will be free of the oppression of apartheid.

Pholoso infers that women will not only be instrumental in fighting for this new, racially equitable social order. Black men also need to prepare for this time of freedom by ensuring that women and men are fully prepared and able to partake in its fruits.

Another vignette from the novel deals with the sexual abuse and rape of young women activists while in detention. Here Tlali chillingly notes that rape and sexual abuse in prison is:

the price we have to pay for our liberation. We have to fight hard and free ourselves, otherwise these things will always happen to us.

These words seem an uncanny foreshadowing of the high rape and sexual abuse rates women would experience after apartheid. It draws into question whether the revolution against apartheid has been fully completed through overcoming only racial oppression.

It also carries a deliberately ambiguous meaning – while the “we” having to fight hard to free “ourselves” signifies the struggle against apartheid, it additionally invokes black women’s gendered struggle against sexual violence. Here, women are being called to simultaneously fight racial oppression while fighting the sexist oppression that spawns rape and sexual abuse.

In “Amandla”, Tlali thus negotiates Black Consciousness ideology by producing a critique of apartheid rooted in Black Consciousness. Simultaneously she complicates the discourse by showing the gendered experiences of sexual harassment that are singular to black women during the 1976 uprising.

“Amandla” provides a rich historical rendering of one of the turning points in the anti-apartheid struggle. It also gives an insightful analysis of the gender politics of the time. Given this content and context, the novel has great potential to contribute to contemporary discussions of violence against women, especially within national student movements.

Disagreements about the role of gender and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and questioning (LGBTIQ) students’ role within the most recent student protests seems to have split the movement. Tlali’s novel provides an instructive critique of the gender politics of Black Consciousness, an ideology that has been forcefully reasserted in these most recent protests.

With its strong position on gender relations within Black Consciousness organising, “Amandla” is worth revisiting by student activists seeking to negotiate an ethical path between economic, racial and gender equity demands. Its didactic aims, instead of being dismissed as aesthetically unappealing, could be well utilised in reframing, for young men in particular, the historical events of the 1976 uprising. It could also be a blueprint for avoiding a repeat of the mistakes then made regarding women’s participation in political movements.

Tlali uses Black Consciousness discourse as a launching point for this vision of masculinity. The novel tracks the life of the student leader, Pholoso, and a range of minor characters.

The reader follows Pholoso as he becomes a leader of the youth. In this role he has conscientising sessions in the cellar of a church with young people active in the struggle. Here Tlali allows him long streams of dialogue. He outlines several position statements from the underground resistance movement on how society should be organised.

Relationships between black men and women is one area where he “instructs” the youth on ethical behaviour. In one scene, Pholoso addresses a room of 22 activists as “Ma-Gents”, making it clear that the room is filled with young men. Within this masculinised space, Pholoso articulates, among other things, a strong position on gender equality and relationships with women.

First, he addresses the absence of women from the “innermost core” of the underground movement this gathering represents. He attributes women’s absence to the high levels of sexual harassment to which women are subject whenever they move around Soweto.

Pholoso names this scourge of molestation as an impediment to women’s participation in political activity. He believes it should be countered through educating the public at large.

Critics such as Cecily Lockett and Kelwyn Sole have critiqued Pholoso’s centrality as a student leader. They have also scrutinised the masculine space wherein he operates as reifying women’s subservient positions within the anti-apartheid struggle. Margaret Miller makes the case that Pholoso’s utterances confirm the marginal role women seemingly played in the 1976 uprising in his “patronising and contradictory” speech.

What critiques such as Miller’s ignore are the reasons Tlali may have for recruiting a black man in the role of gender conscientising. He is equated with Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt, to disseminate a message of gender parity through the community.

In addressing the “Ma-Gents” on the sexual harassment, treatment and education of women, Pholoso advocates an oppositional black masculinity to counter dominant iterations of masculinity in Soweto. He exhorts the men to “go out and educate the people”. Pholoso is reliant on a ripple effect his message will have as it spreads out in concentric circles among the township’s men.

It is important to note that he is not addressing white men or women and their treatment of black women, but black men specifically. A black man himself, he holds black men as a group accountable for the safety, education and equitable treatment of women. He is gesturing to a time as yet unknown, in the future, when black subjects will be free of the oppression of apartheid.

Pholoso infers that women will not only be instrumental in fighting for this new, racially equitable social order. Black men also need to prepare for this time of freedom by ensuring that women and men are fully prepared and able to partake in its fruits.

Another vignette from the novel deals with the sexual abuse and rape of young women activists while in detention. Here Tlali chillingly notes that rape and sexual abuse in prison is:

the price we have to pay for our liberation. We have to fight hard and free ourselves, otherwise these things will always happen to us.

These words seem an uncanny foreshadowing of the high rape and sexual abuse rates women would experience after apartheid. It draws into question whether the revolution against apartheid has been fully completed through overcoming only racial oppression.

It also carries a deliberately ambiguous meaning – while the “we” having to fight hard to free “ourselves” signifies the struggle against apartheid, it additionally invokes black women’s gendered struggle against sexual violence. Here, women are being called to simultaneously fight racial oppression while fighting the sexist oppression that spawns rape and sexual abuse.

In “Amandla”, Tlali thus negotiates Black Consciousness ideology by producing a critique of apartheid rooted in Black Consciousness. Simultaneously she complicates the discourse by showing the gendered experiences of sexual harassment that are singular to black women during the 1976 uprising.

“Amandla” provides a rich historical rendering of one of the turning points in the anti-apartheid struggle. It also gives an insightful analysis of the gender politics of the time. Given this content and context, the novel has great potential to contribute to contemporary discussions of violence against women, especially within national student movements.

Disagreements about the role of gender and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and questioning (LGBTIQ) students’ role within the most recent student protests seems to have split the movement. Tlali’s novel provides an instructive critique of the gender politics of Black Consciousness, an ideology that has been forcefully reasserted in these most recent protests.

With its strong position on gender relations within Black Consciousness organising, “Amandla” is worth revisiting by student activists seeking to negotiate an ethical path between economic, racial and gender equity demands. Its didactic aims, instead of being dismissed as aesthetically unappealing, could be well utilised in reframing, for young men in particular, the historical events of the 1976 uprising. It could also be a blueprint for avoiding a repeat of the mistakes then made regarding women’s participation in political movements.

Miriam Tlali’s 1980 novel, Amandla, offers one of South Africa’s most detailed accounts of the 1976 Soweto uprising from the perspective of a number of young revolutionaries of the time. Based on events Tlali witnessed as a resident of Soweto during 1976, the novel offers a detailed portrayal of Black Consciousness ideology in the service of anti-apartheid activism, while explicating gender relations between men and women activists and members of the larger community. This essay focuses on the ways in which Amandla, Tlali’s second novel, constructs black, revolutionary masculinity in ways that hold valuable lessons for democratic, post-apartheid South Africa as it grapples with high rates of gender-based violence. I argue that through the main character of Pholoso and a host of women characters with whom he interacts, Tlali offers a blueprint for a politically engaged masculinity which refuses to articulate itself through patriarchal hegemony, while accommodating and encouraging women’s autonomy, equality, and leadership in political activity. The novel also engages with the issue of domestic violence, demonstrating a community response to violent masculinity that doesn’t undermine black unity. Critically ignored upon publication and in both apartheid and post-apartheid literary canons, Amandla’s militant depiction of the Soweto uprising is worth revisiting for its insights on masculinity, revolution and gender relationships within the cauldron of political upheaval.

The book offers a detailed fictional account of the event, drawing from Tlali’s own experiences as a Soweto residents during the Uprisings. The book also detailed the inner workings of student movements and the mechanisms of Black Consciousness, the engine of liberation movements at the time.

But unlike other fictional works depicting the 1976 Uprisings, such as Mongane Serote’s “To Every Birth it’s Blood” (1981) and Mbulelo Mzamane’s “The Children Of Soweto” (1982), “Amandla” deviates from a heavy focus on Black Consciousness and instead looks further into gender politics of 1976 Soweto.

The novel constructs a new vision of Black Masculinity rooted in Black consciousness and laments the movement’s lack of intersectionality, following the life of Pholoso, as he becomes the leader of the movement and takes a string stands on gender equality within the movement. The book, without its own critiques and controversies, could be seen as a blueprint to avoid making the same mistakes in the future.

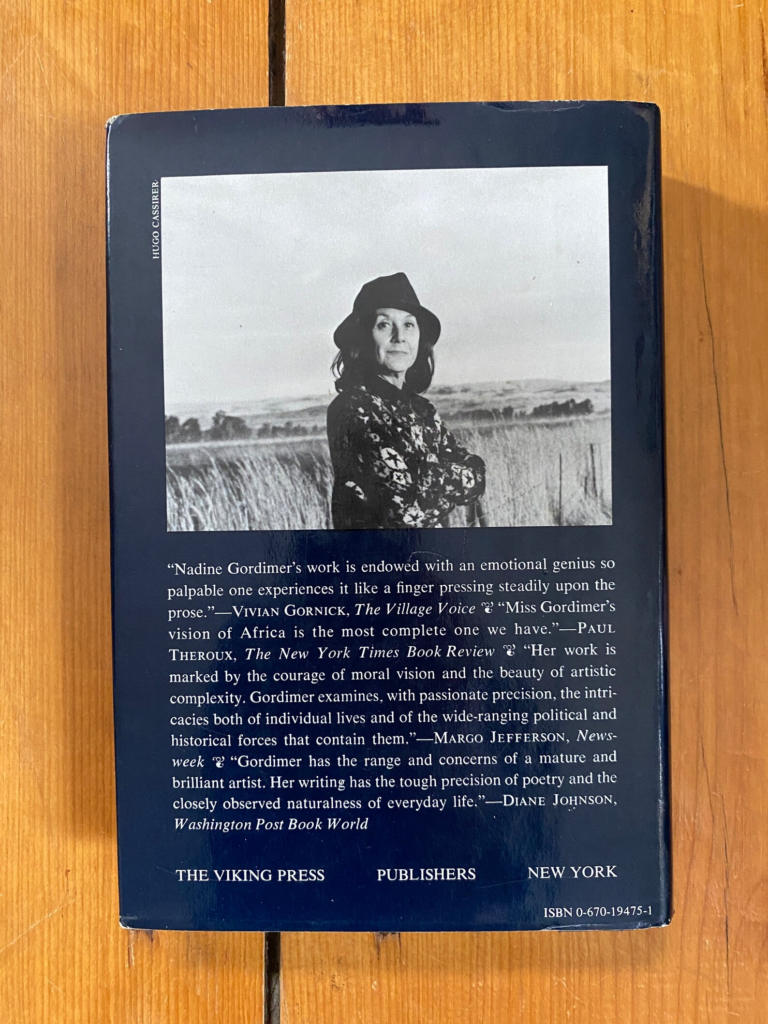

4) “BURGER’S DAUGHTER” by NADINE GORDIMER, 1979

Nadine Gordimer is one of the most influential writers in South African literary history. “Burger’s Daughter”, the late Noble prize winner’s seventh novel, delves deep into the author’s political stance in the face of the apartheid regime.

The book revolves around the life and journey of the central character, Rosa Burger, during 1974-1977 apartheid South Africa. Raised by a white Anti-apartheid activist mother and father who both died in Prison, Rosa later becomes an activist herself but it is plagued by a guilt of white privilege that leads to her own incarceration.

Burger’s Daughter is a political and historical novel by the South African Nobel Prize in Literature-winner Nadine Gordimer, first published in the United Kingdom in June 1979 by Jonathan Cape. The book was expected to be banned in South Africa, and a month after publication in London the import and sale of the book in South Africa was prohibited by the Publications Control Board. Three months later, the Publications Appeal Board overturned the banning and the restrictions were lifted.

Burger’s Daughter details a group of white anti-apartheid activists in South Africa seeking to overthrow the South African government. It is set in the mid-1970s, and follows the life of Rosa Burger, the title character, as she comes to terms with her father Lionel Burger’s legacy as an activist in the South African Communist Party (SACP). The perspective shifts between Rosa’s internal monologue (often directed towards her father or her lover Conrad), and the omniscient narrator. The novel is rooted in the history of the anti-apartheid struggle and references to actual events and people from that period, including Nelson Mandela and the 1976 Soweto uprising.

Gordimer herself was involved in South African struggle politics, and she knew many of the activists, including Bram Fischer, Mandela’s treason trial defence lawyer. She modelled the Burger family in the novel loosely on Fischer’s family, and described Burger’s Daughter as “a coded homage” to Fischer. While banned in South Africa, a copy of the book was smuggled into Mandela’s prison cell on Robben Island, and he reported that he “thought well of it”.

The novel was generally well-received by critics. A reviewer for The New York Times said that Burger’s Daughter is Gordimer’s “most political and most moving novel”, and a review in The New York Review of Books described the style of writing as “elegant”, “fastidious” and belonging to a “cultivated upper class”. A critic in The Hudson Review had mixed feelings about the book, saying that it “gives scarcely any pleasure in the reading but which one is pleased to have read nonetheless”. Burger’s Daughter won the Central News Agency Literary Award in 1980.

The novel begins in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1974 during apartheid. Rosa Burger is 26, and her father, Lionel Burger, a white Afrikaner anti-apartheid activist, has died in prison after serving three years of a life sentence for treason. When she was 14, her mother, Cathy Burger, also died in prison. Rosa had grown up in a family that actively supported the overthrow of the apartheid government, and the house they lived in opened its doors to anyone supporting the struggle, regardless of colour. Living with them was “Baasie” (little boss), a black boy Rosa’s age the Burgers had “adopted” when his father had died in prison. Baasie and Rosa grew up as brother and sister. Rosa’s parents were members of the outlawed South African Communist Party (SACP), and had been arrested several times when she was a child. When Rosa was nine, she was sent to stay with her father’s family; Baasie was sent elsewhere, and she lost contact with him.

With the Burger’s house now empty, Rosa sells it and moves in with Conrad, a student who had befriended her during her father’s trial. Conrad questions her about her role in the Burger family and asks why she always did what she was told. Later Rosa leaves Conrad and moves into a flat on her own and works as a physiotherapist. In 1975 Rosa attends a party of a friend in Soweto, and it is there that she hears a black university student dismissing all whites’ help as irrelevant, saying that whites cannot know what blacks want, and that blacks will liberate themselves. Despite being labelled a Communist and under surveillance by the authorities, Rosa manages to get a passport, and flies to Nice in France to spend several months with Katya, her father’s first wife. There she meets Bernard Chabalier, a visiting academic from Paris. They become lovers and he persuades her to return with him to Paris.

Before joining Bernard in Paris, Rosa stays in a flat in London for several weeks. Now that she has no intention of honouring the agreement of her passport, which was to return to South Africa within a year, she openly introduces herself as Burger’s daughter. This attracts the attention of the media and she attends several political events. At one such event, Rosa sees Baasie, but when she tries to talk to him, he starts criticising her for not knowing his real name (Zwelinzima Vulindlela). He says that there is nothing special about her father having died in prison as many black fathers have also died there, and adds that he does not need her help. Rosa is devastated by her childhood friend’s hurtful remarks, and overcome with guilt, she abandons her plans of going into exile in France and returns to South Africa.

Back home she resumes her job as a physiotherapist in Soweto. Then in June 1976 Soweto school children start protesting about their inferior education and being taught in Afrikaans. They go on a rampage, which includes killing white welfare workers. The police brutally put down the uprising, resulting in hundreds of deaths. In October 1977, many organisations and people critical of the white government are banned, and in November 1977 Rosa is detained. Her lawyer, who also represented her father, expects charges to be brought against her of furthering the aims of the banned SACP and African National Congress (ANC), and of aiding and abetting the students’ revolt.

In a 1980 interview, Gordimer stated that she was fascinated by the role of “white hard-core Leftists” in South Africa, and that she had long envisaged the idea for Burger’s Daughter. Inspired by the work of Bram Fischer, she published an essay about him in 1961 entitled “Why Did Bram Fischer Choose to Go to Jail?” Fischer was the Afrikaner advocate and Communist who was Nelson Mandela‘s defence lawyer during his 1956 Treason Trial and his 1965 Rivonia Trial. As a friend of many of the activist families, including Fischer’s, Gordimer knew these families’ children were “politically groomed” for the struggle, and were taught that “the struggle came first” and they came second. She modelled the Burger family in the novel loosely on Fischer’s family, and Lionel Burger on Fischer himself. While Gordimer never said the book was about Fischer, she did describe it as “a coded homage” to him. Before submitting the manuscript to her publisher, Gordimer gave it to Fischer’s daughter, Ilse Wilson (née Fischer) to read, saying that, because of connections people might make to her family, she wanted her to see it first. When Wilson returned the manuscript to Gordimer, she told the writer, “You have captured the life that was ours.” After Gordimer’s death in July 2014, Wilson wrote that Gordimer “had the extraordinary ability to describe a situation and capture the lives of people she was not necessarily a part of.”

Gordimer’s homage to Fischer extends to using excerpts from his writings and public statements in the book. Lionel Burger’s treason trial speech from the dock is taken from the speech Fischer gave at his own trial in 1966. Fischer was the leader of the banned SACP who was given a life sentence for furthering the aims of communism and conspiracy to overthrow the government. Quoting people like Fischer was not permitted in South Africa. All Gordimer’s quotes from banned sources in Burger’s Daughter are unattributed, and also include writings of Joe Slovo, a member of the SACP and the outlawed ANC, and a pamphlet written and distributed by the Soweto Students Representative Council during the Soweto uprising.

Gordimer herself became involved in South African struggle politics after the arrest of a friend, Bettie du Toit, in 1960 for trade unionist activities and being a member of the SACP. Just as Rosa Burger in the novel visits family in prison, so Gordimer visited her friend. Later in 1986, Gordimer gave evidence at the Delmas Treason Trial in support of 22 ANC members accused of treason. She was a member of the ANC while it was still an illegal organization in South Africa, and hid several ANC leaders in her own home to help them evade arrest by the security forces.

The inspiration for Burger’s Daughter came when Gordimer was waiting to visit a political detainee in prison, and amongst the other visitors she saw a school girl, the daughter of an activist she knew. She wondered what this child was thinking and what family obligations were making her stand there. The novel opens with the same scene: a 14-year-old Rosa Burger waiting outside a prison to visit her detained mother. Gordimer said that children like these, whose activist parents were frequently arrested and detained, periodically had to manage entire households on their own, and it must have changed their lives completely. She stated that it was these children who encouraged her to write the book.

Burger’s Daughter took Gordimer four years to write, starting from a handful of what she called “very scrappy notes”, “half sentences” and “little snatches of dialogue”. Collecting information for the novel was difficult because at the time little was known about South African communists. Gordimer relied on clandestine books and documents given to her by confidants, and her own experiences of living in South Africa. Once she got going, she said, writing the book became an “organic process”. The Soweto riots in 1976 happened while she was working on the book, and she changed the plot to incorporate the uprising. Gordimer explained that “Rosa would have come back to South Africa; that was inevitable”, but “[t]here would have been a different ending”. During those four years she also wrote two non-fiction articles to take breaks from working on the novel.

Gordimer remarked that, more than just a story about white communists in South Africa, Burger’s Daughter is about “commitment” and what she as a writer does to “make sense of life”. After Mandela and Fischer were sentenced in the mid-1960s, Gordimer considered going into exile, but she changed her mind and later recalled “I wouldn’t be accepted as I was here, even in the worst times and even though I’m white”. Just as Rosa struggles to find her place as a white in the anti-apartheid liberation movement, so did Gordimer. In an interview in 1980, she said that “when we have got beyond the apartheid situation—there’s a tremendous problem for whites, unless whites are allowed in by blacks, and unless we can make out a case for our being accepted and we can forge a common culture together, whites are going to be marginal”.

Publication and banning

Gordimer knew that Burger’s Daughter would be banned in South Africa. After the book was published in London by Jonathan Cape in June 1979, copies were dispatched to South Africa, and on 5 July 1979 the book was banned from import and sale in South Africa. The reasons given by the Publications Control Board included “propagating Communist opinions”, “creating a psychosis of revolution and rebellion”, and “making several unbridled attacks against the authority entrusted with the maintenance of law and order and the safety of the state”.

In October 1979 the Publications Appeal Board, on the recommendation of a panel of literary experts and a state security specialist, overruled the banning of Burger’s Daughter. The state security specialist reported the book posed no threat to the security of South Africa, and the literary experts had accused the censorship board “of bias, prejudice, and literary incompetence”, and that “[i]t has not read accurately, it has severely distorted by quoting extensively out of context, it has not considered the work as a literary work deserves to be considered, and it has directly, and by implication, smeared the authoress [sic]. Notwithstanding the unbanning, the chairman of the Appeal Board told a press reporter, “Don’t buy [the book]—it is not worth buying. Very badly written … This is also why we eventually passed it.” The Appeal Board described the book as “one-sided” in its attack on whites and the South African Government, and concluded, “As a result … the effect of the book will be counterproductive rather than subversive.”

Gordimer’s response to the novel’s unbanning was, “I was indifferent to the opinions of the original censorship committee who neither read nor understood the book properly in the first place, and to those of the committee of literary experts who made this discovery, since both are part of the censorship system.” She attributed the unbanning to her international stature and the “serious attention” the book had received abroad. A number of prominent authors and literary organisations had protested the banning, including Iris Murdoch, Heinrich Böll, Paul Theroux, John Fowles, Frank Kermode, The Association of American Publishers and International PEN. Gordimer objected to the unbanning of the book because she felt the government was trying placate her with “special treatment”, and said that the same thing would not have happened had she been black. But she did describe the action as “something of a precedent for other writers” because in the book she had published a copy of an actual pamphlet written and distributed by students in the 1976 Soweto uprising, which the authorities had banned. She said that similar “transgressions” in the future would be difficult for the censors to clamp down on.

While Burger’s Daughter was still banned in South Africa, a copy was smuggled into Nelson Mandela’s prison cell on Robben Island, and later a message was sent out saying that he had “thought well of it”. Gordimer said, “That means more to me than any other opinion it could have gained.” Mandela also requested a meeting with her, and she applied several times to visit him on the Island, but was declined each time. She was, however, at the prison gates waiting for him when he was released in 1990, and she was amongst the first he wanted to talk to. In 2007 Gordimer sent Mandela an inscribed copy of Burger’s Daughter to “replace the ‘imprisoned’ copy”, and in it she thanked him for his opinion of the book, and for “untiringly leading the struggle”.

To voice her disapproval of the banning and unbanning of the book, Gordimer published What Happened to Burger’s Daughter or How South African Censorship Works, a book of essays written by her and others. It was published in Johannesburg in 1980 by Taurus, a small underground publishing house established in the late-1970s to print anti-apartheid literature and other material South African publishers would avoid for fear of censorship. Its publications were generally distributed privately or sent to bookshops to be given to customers free to avoid attracting the attention of the South African authorities.

What Happened to Burger’s Daughter has two essays by Gordimer and one by University of the Witwatersrand law professor John Dugard. Gordimer’s essays document the publication history and fate of Burger’s Daughter, and respond to the Publications Control Board’s reasons for banning the book. Dugard’s essay examines censorship in South Africa within the country’s legal framework. Also included in the book is the Director of Publications’s communiqué stating its reasons for banning the book, and the reasons for lifting the ban three months later by the Publications Appeal Board.[

Publication history

Burger’s Daughter was first published in the United Kingdom, in hardcover, in June 1979 by Jonathan Cape, and October that year in the United States, also in hardcover, by Viking Press. The first paperback edition was published in the United Kingdom in November 1980 by Penguin Books. A unabridged 12-hour-51-minute audio cassette edition, narrated by Nadia May, was released in the United States in July 1993 by Blackstone Audio.

Burger’s Daughter has been translated into several other languages since its first publication in English in 1979:

The book touches on themes of white communism and the lives of people involved in the then Outlawed South African Communist Party (SACP), which Bram Fischer was the leader of Gordimer’s homage to Fischer even went as far as using excerpts of his writings and public speaking in his books.

In a 1980 interview, she remarked that the book was about more than a white communist suffering from a white guilt, but rather that it was a story of commitment. Gordimer also predicted the marginalization of white liberals in post-apartheid South Africa, saying “Unless whites are allowed in by the blacks” and unless we make out a case for our being accepted and we can forge a common culture together, whites are going to be marginal”

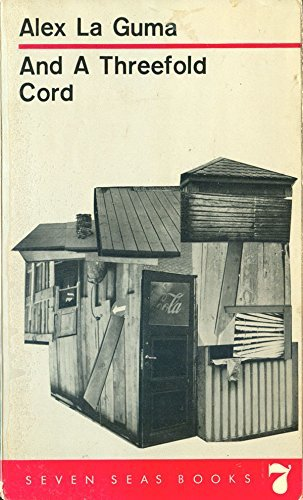

5) “AND A THREEFOLD CORD”, by ALEX LA GUMA, 1964

The Late Alex LA Guma is one of the most important Black literary figures of the 20th Century in South Africa. His second novel, “And A Three-fold Cord” (1964), is set in the Cape Flats and explores contemporary themes of Class Conflicts.

The centrality of the working class in the matrix of social tension and strife in South Africa is

revealed in the works Alex La Guma. La Guma’s And a Threefold Cord forms a starting point, a

key, to the pattern which his novel form. The purpose of this paper is why the workers become

violent in rainy environment and its effects on the working class family, La Guma expands to

the macro-environment of the working class in the novel. The family and the working class

district form the background to which the political movement can be understood. The

underground liberation movement is portrayed as a working class organisation fighting against

racist oppression and exploitation.

This novel is published in 1964 and is set in the Cape Flats, an impoverished area near Cape Town. It

analyses the predicament of the shanty dwellers in terms of class inequality and economic exploitation,

rather than in terms of racial discrimination. This ensures the novel’s continuing relevance in a South

Africa where far too many people are inadequately housed in ever-growing “informal settlement. This

book is a critique of apartheid South Africa. The plot of And a Threefold Cord is slight and may be

summarily outlined. The Pauls family – Dad and Ma Pauls, their sons Charlie, Ronald and Jonny – live

in a miserable three-roomed “pondokkie” somewhere on the Cape Flats. As the narrative begins, the

onset of rough weather is posing an additional threat to the already precarious security of their lives.

In this regard the focal point of La Guma’s art is the working class which plays an important role in the

portraits of struggle in the novels. In this study the term “working class” will be used to denote the

labouring social category involved in production in an industrial economy. This implies a contrasting

social group, a hostile class, the bourgeoisie, which, unlike the working class, owns property. Although

the actual counter term for “bourgeoisie” is “proletariat”, within the context of this study we shall prefer

working class, having in mind the fact that the term proletariat has a more specialized meaning and is

used often to mean a working class in the actual process of struggle as an ideological and political force

fighting against the bourgeoisie.

Mark Vorobej’s says “We all live that are to an extraordinary extent, mired in violence”. This

sentence seems to articulate an incisive experience motivating the whole enquiry. This

statement is a general consideration about the irreducible character of violence in human

societies and lives that qualifies this phenomenon as a matter of philosophical enquiry as a

concept for thinking. For Vorobej the concept of violence is “a complex, unwieldy and highly

contested concept” as well as “highly ambiguous and extremely vague”.

Violence needs philosophy. The quest to fully understand what violence is, why violence raises

fundamental social, political and moral questions, and whether violence can ever be justified,

would suffer immeasurably unless it took full advantage of the skills that are peculiar to those

trained in philosophy. Violence has captured the imagination of philosophers; the interest has

tended to focus on specific forms of violence, such as terrorisyoe nature as communal beings.

In a move reminiscent of Sade’s, Hegel argues that individuals rise to the level of Being-for-self

only by denying their communal nature in an act of violence against other human beings. By

defining violence as the destruction of the social realm by social beings, Hegel shows both his

romantic heritage and the fundamental insight of romanticism, namely that violence is only

and always a form of human conflict. Nevertheless, his desire to trace the purely logical

development of Being-for-itself transforms violence into a logical device, an idealism, serving

his definition of being. Indeed, violence is the primary educator of Being-for-itself: in the life

and death struggle of violence, the self discovers a violence (the violence of the other) that

escapes its violence and that threatens its entire existence, thus recognizing the reality of

other individuals. Through violence, the self attains a universal point of view in which the

dynamic of self and other may be conceptualized.

In the works of Alex La Guma three main aspects can be “isolated which are essential to his artistic

technique and which also are indications of his ideological orientation. The first is his relation of

character to circumstance. This springs from the materialist view that circumstance, like the base

determines character. The second is the broad emphasis in the portrait of the working class and the

central role the class is given in the novels. Tied closely to this is La Guma’s emphasis on the youth of

this social category which indicates his faith not only in the working class as the motive force in the

national liberation struggle in South Africa, but also his faith in the youth as the bearers of hope for the

future. Thirdly there is in La Guma’s narrative technique the implicit expression of optimism in all his

novels which shows his firm belief in the future.

Alex la Guma’s novel And a Threefold Cord tells the story of a rain drenched ghetto in South Africa.

At the centre of this ghetto, pulsating with hate and love, despair of poverty and a passionate strife for

freedom from squalor, whose clutch is as real as the rain that pours incessantly, is the Pauls family: there

is Charlie, Ronny and Johnny, their sister Caroline, their mother and an aged and ailing father. The

Pauls are pitted against nature, harsh and unrelenting on the one hand, and on the other, there is the

harsh and brutish action of the police. The rain, and later the police, are portrayed as competing to

submerge the ghetto and the people living in it into darkness and pain: On the north-west the rain heads

piled up, first in Cottony trufts blown by the high wind, then in skeins of dull cloud and finally in high

climbing battlements like a rough wall of mortal built across the horizon, so that the sun had no gleam,

— but a pale phosphorescence behind the veil of grey.2 I \ Beneath “the rough wall of mortar” the Pauls

and other ghetto dwellers are forced – a shivering horde crudely improvising to keep away the chill and

the wetness. In.spite of their efforts the darkness still engulfs them with the blankness of a sealed cave.

With this coldness and darkness of nature is the metallic coldness and violence of the police who lurk in

the shadows and the swamped door-yards, their boots “sucking and belching”

Nature as Enemy

Lacking the means to adequately defend themselves against the onslaught of bad weather, they

encounter onslaught of bad weather, they encounter Nature itself as a hostile force, an enemy as

malevolent and inscrutable as the pol ice convoy that comes in the darkness and wet to devastate their

lives. Indeed, rain and wind preside over the police raid like willing henchmen, exacerbating the misery

of those who have been turned out of their homes and arrested. But when the police depart, their

confederates in oppression remain, growling “like 11 hungry monster”, attacking the squatters “with

ferocity” (

The condition of a working class family in South Africa as it is portrayed in the novel And a

Threefold Cord. The purpose is also to show how the micro-environment of the family is affected by the

exploitative and oppressive society around it. The effects of exploitation and the extent of other social

pressures which confound the # family to a daily existence of misery, privation and general squalor are

brought out by the author in this novel. The Pauls are shown as a typical working class family, a unit

struggling to live within a broader class of people already far removed (expropriated) from all means of

production. We see idleness, joblessness, lack of proper shelter and medical attention, and a general

absence of all those amenities and conveniences that would make life passably comfortable. The

incidence of all these inadequacies falls on the family as the smallest unit in society. The results are

disastrous, I as the pressures lead to an internal disintegration where the members of the family cannot

stand these tensions emanating from society. The examination of the family therefore provides a starting

point towards a general understanding of the larger social category, i.e., the working class in South

Africa.

La Guma in this novel focuses on the Pauls family, as a typical unit from the working class, the

inclusion of brief statements about the rich white South African family serves the purpose of

illuminating two things. First it tells us that on that on the other side of the rain drenched, chilly and

depressing slum is a well ordered, r comfortable and rich haven of the rich. The workers who live in the

dreary atmosphere of the slum have contributed to the beauty of the rich by working to set up those

conveniences that the rich enjoy. Charlie’s reference to “laying pipes by Calving” is an indication of this.

Although the workers create the beauty, they live in wretchedness and perpetual want. Although Charlie

lays water pipes leading to the big mansions, the Pauls can hardly find water to bath the dead Dad Pauls

or Caroline’s new born baby. Secondly, Charlie’s statements referring to the whites I bring out the reality

of apartheid: “Jubas like me can’t even touch the handle of the front door.” This is later seen in the

relationship between Charlie and George Mostert. Mostert would like to strike a friendship with Charlie,

but we learn that he chooses to do so under cover of darkness. Although the rendezvous between the two

is not kept, their conversation reveals the uneasy relationship between on black and white.

The novelist gives focus on the economic deprivation on the lives of the inhabitants of the ghetto. For

the Pauls it means an inadequate diet, poor living quarters, poor sanitation, non-existent health facilities,

joblessness, and a generally insecure livelihood. Old Dad Pauls is compelled to live in a damp

environment in his poor health. He eventually dies without proper medical attention. Caroline is

compelled to have her baby on a bed of newspapers and rags. And Freda loses her house and children in

a fire accident which guts her shack. In the novel we see that the people, shut in this vault-like situation,

live a precarious existence. The bad situation is worsened by the added terror of the police who patrol

the ghetto, interrupting whatever little peace there is. The occurrence of violence at the slightest

provocation, seems to indicate that the pressure on the people is unbearable.

We have seen a portrait of a working class family and how it is conceived with the

matrix of economic exploitation, segregation an oppressive social arrangement. The family being

smallest social unit was examined first here as it relates to the pattern discerned in the works of A La

Guma. In understanding the place and condition of the working class family it will be easy to

understand the condition of the working class in general. La Guma, in starting from the particular (the

micro-environment of the family) and building towards the general (macro-environment of the society)

builds a relation.

The condition of a working class family in an exploitative and violent social environment. La Guma’s

portraits of struggle spring from its centrality in the social and political arena of South Africa. La Guma

however does not ignore in his portraits the participation of other social classes or groups nor does he

spare the working class itself. He brings out as effectively the weaknesses and limitations, its errors and

failings as he demonstrates its successes, its strengths and its historical centrality in the politics of South

Africa.

The book tells the haunting tales of a coloured family living in the Shanties of the Cape Flats and their daily struggle to survive. It’s a heavy critique of the apartheid regime and has been praised for it’s accurate representation of economic conditions in the 1960s western cape, where housing shortages displaced many coloured residents at the time. It paints a stark picture of suffering and Defiance in the face of misery, and it succeeded not only in giving the coloured community a much-needed voice, but also a shinning light on the inhumanity of the apartheid regime.

La Guma’s literacy works have been all but forgotten over the years. With the exception of the 1969 lotus prize for Literature, there has been little to no mention of LA Guma’s works on the coloured community outside the confines of the marginal Black political writings. “And A Threefold Cord” is both a superior piece of complex Storytelling and a scathing rebuke of injustice. It should be held to a higher acclaim than it currently is.

6) “CRY, THE BELOVED COUNTRY”, by ALAN PATON, 1948.

First published in 1948, the same year in which the National Party came to Power and with them the official impeachment of the apartheid system, author and Anti-apartheid activist Alan Panton’s Seminal novel went on to become one of the most famous books ever published in South Africa.

The story begins in the village of Ixopo Ndotsheni, where the Christian priest Stephen Kumalo, a Zulu, receives a letter from the priest Theophilus Msimangu in Johannesburg. Msimangu urges Kumalo to come to the city to help his sister Gertrude because she is ill. Kumalo goes to Johannesburg to help her and find his son Absalom, who had gone to the city to look for Gertrude but never came home. It is a long journey to Johannesburg, and Kumalo sees the wonders of the modern world for the first time.

When he gets to the city, Kumalo learns that Gertrude has taken up a life of prostitution and beer brewing and is now drinking heavily. She agrees to return to the village with her young son. Assured by these developments, Kumalo embarks on the search for Absalom, first seeing his brother John, a carpenter who has become involved in the politics of South Africa. Kumalo and Msimangu follow Absalom’s trail, only to learn that Absalom has been in a reformatory and will have a child with a young woman. Shortly thereafter, Kumalo discovers that his son has been arrested for murder. The victim is Arthur Jarvis, a white man who was killed during a burglary. Jarvis was an engineer and an activist for racial justice and is the son of Kumalo’s neighbour, James Jarvis.

Jarvis learns of his son’s death and comes with his family to Johannesburg. Jarvis and his son had been distant, and now the father begins to know his son through his writings. Through reading his son’s essays, Jarvis decides to take up his son’s work for South Africa’s black population.

Absalom reveals at his trial that he was pressured into committing the burglary by and with his three “friends”, who later denied their involvement and threw all the blame on Absalom . Absalom is sentenced to death for the murder of Arthur Jarvis. Before his father returns to Ndotsheni, Absalom marries the girl carrying his child. She joins Kumalo’s family. Kumalo returns to his village with his daughter-in-law and nephew, having found that Gertrude ran away the night before their departure.

Back in Ixopo, Kumalo makes a futile visit to the tribe’s chief to discuss changes that must be made to help the barren village. Help arrives, however, when James Jarvis becomes involved in the work. He arranges for a dam to be built and hires a native agricultural demonstrator to implement new farming methods.

The novel ends at dawn on the morning of Absalom’s execution. The fathers of the two children are devastated that both of their sons have wound up dead.

Characters

- Stephen Kumalo: A 60-year-old Christian Zulu priest, the father of Absalom, who attempts to find his family in Johannesburg, and later to reconstruct the disintegrating state of his village. Book three focuses heavily on his relationship with James Jarvis.

- Theophilus Msimangu: A priest from Johannesburg who helps Kumalo find his son Absalom and his sister Gertrude.