African Literary Magazines and journals don’t just shape literary culture, they offer the most rebellious responses to political and social movements. They not only respond to the cultures they’re in, these magazines also creates distinct cultures they’re in, these magazines also creates distinctive cultures of their own that reflects the personalities of their editors.

Some are experimental and bold, some are satirical and polemic, some can also be Aesthetically Conservative, but they all find beautiful ways to confront the most pressing issues in the society. Magazines archive stories that might not always gain the attention that books will, but are sometimes the most thrilling work in a writer’s career.

“Do Magazines cultures?” Rajat Neogy, the founder of Transition Magazines, once asked.

Now let’ take a look back at these literary magazines and journals that shaped what African literature is today

Here are the most notable literary magazines that have shaped contemporary African literature

1)“JALADA”

The Jalada literary collective has a radical mission: an ongoing translation effort to unite— and elevate—African literature.

Writing about (and critiquing the idea of) African literary generations, Keguro Macharia once said, “If one is slightly cheeky, the fourth generation lives in Chimamanda’s inbox. More seriously, it is incarnated in the border-crossing collective work of JALADA”.

While the other literary magazines and journals were mostly print magazines, JALADA represents the digital moments where African literature is thriving on Online platforms like Saraba, Enkare and Brittle Paper.

JALADA began after a group of writers from various African countries published their work on their own website which became so popular they began receiving submissions from other writers. The platform has since had exciting themes for their issues like insanity, sex, Afrofuturism, and translation. Notable contributors include Clifton Gachagua, Tsitsi Jaji, Novuyo Tshuma, Moses Kiloma, Wanjeri Ghakulu and Mehul Gohil.

Founded in 2013, the pan-African collective Jalada is unarguably at the forefront of the reinvention of African literature. In this period of time, the group has published five important anthologies and one mini-anthology.

It began with a workshop for young writers in Nairobi in 2013, organized by the Kwani Trust and the British Council. As Moses Kilolo recalls, he had never attended a writing workshop before. Like so many of his peers, he had been toiling alone: Each day he would haunt his university library, struggling in his own writing to imitate the English-language classics that he found on the shelves. It was a remarkably well-stocked library, as he remembers it, the best a young writer could hope for. Yet while he had produced a few halting efforts at prose, he hadn’t yet “come out” as a writer. He stayed in the stacks. It was only after the three-day workshop with a dozen other young writers, he says, that the brilliance of his peers pulled him out of the library—helped him to realize what he could never accomplish alone. “I wasn’t as good as I thought,” he laughs. “They tore my work apart! It was moving to know that there’s so much more possibility.”

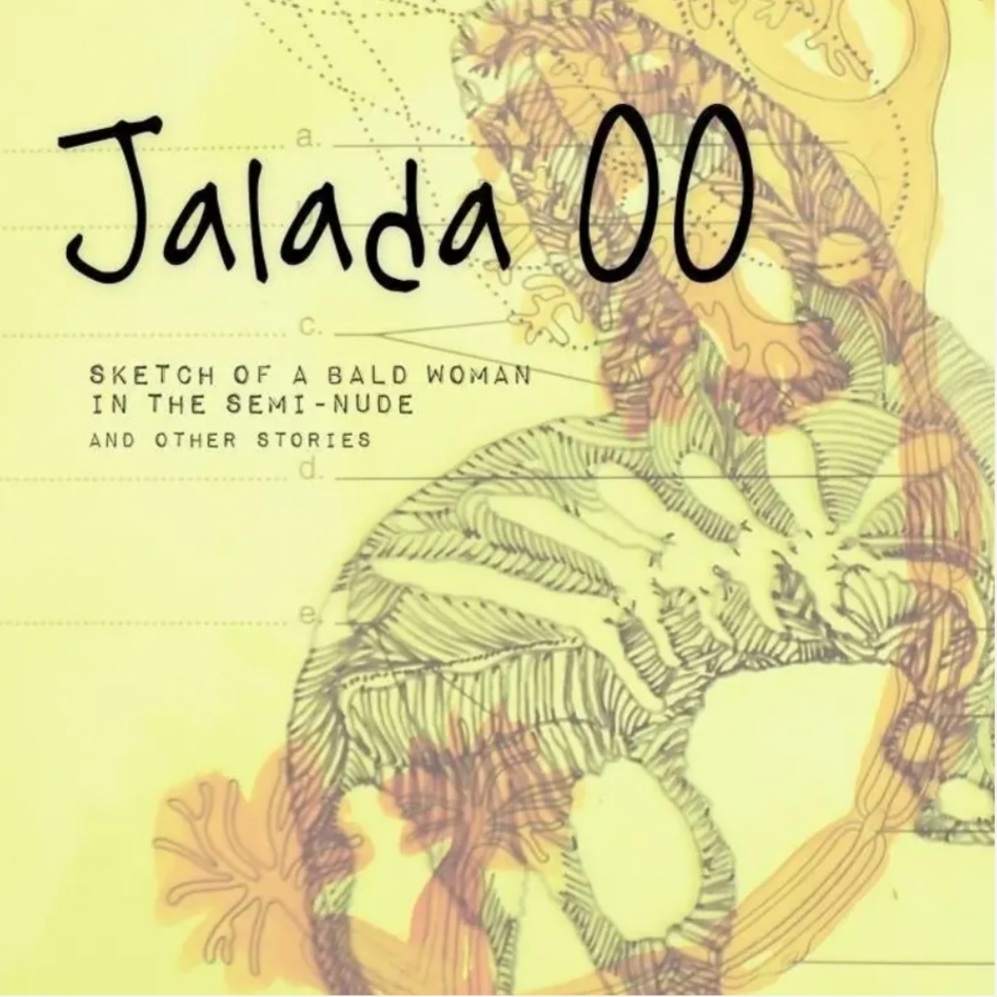

The feeling was general among the workshop’s participants. At first they stayed in touch out of a spontaneous desire to keep the conversations going. But after Okwiri Oduor—who would win the Caine Prize for African Writing later in the year—set up a Google group named Jalada, after the word for library in Kiswahili, the group began to evolve into something more concrete. As the members began writing, and editing each other’s work, they also began talking about what hadn’t been written yet, and what needed to be. They began building their own library: A few months after the workshop, they set up a bare-bones website (jalada.org) where they published an anthology of original work loosely themed around the notion of insanity, Sketch of a Bald Woman in the Semi-Nude and Other Stories.

It had been an easy choice to publish on the Internet: It was free, it was easy, and they had complete control. As the word spread—and as the inaugural anthology did the rounds on social media—they began hearing from writers across the continent, asking if they could submit to the next anthology. Jalada’s editors said yes. The second collection—Sext Me: Poems and Stories, on the intersections of sex and technology, and twice as long as the first—included a handful of participants from outside Kenya, as well as Jalada’s first official call for submissions. Exactly a year after the first anthology, Afrofuture (s)—a three-part shelf-buster of Africanist speculative fiction—had close to a majority of non-Kenyan writers.

As the library has grown from a roomful of young Nairobians to an ongoing conversation that spans the continent—with email, Skype, and social media allowing members in a half-dozen countries to stay in touch—it’s become clear that Jalada is where the future of African literature is being written. A project with a pan-Africanist scope might have drowned under the logistics of communication and distance, or lost its energy in fundraising. Instead, meetings have yielded true mentorships and editorial relationships, and correspondences have blossomed into long-term collaborations, as the contributors to each anthology have become a part of the broader network. The management team remains mostly Kenyan—allowing semi-regular face-to-face meetings—but the structure is as horizontal and outward-looking as possible. Members from Namibia, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Somalia make up the core group, with an even broader network of contributors and collaborators. Richard Ali in Nigeria and Edwige-Renée DRO in Côte d’Ivoire have been crucial to the project’s expanding reach, for example, both for their editorial expertise and for connecting Jalada to new writers in West and Francophone Africa. Building connections with North Africa is the next hurdle.

Jalada’s “about” page is brief and to the point: a “pan-Africanist writers’ collective” whose goal is “to publish literature by African authors regularly by making it as easy as possible for any member to publish anything.” This tautology—their goal is to publish the things they are publishing—tells a story of its own: Jalada is just the work itself, without money, pretensions, or ego.

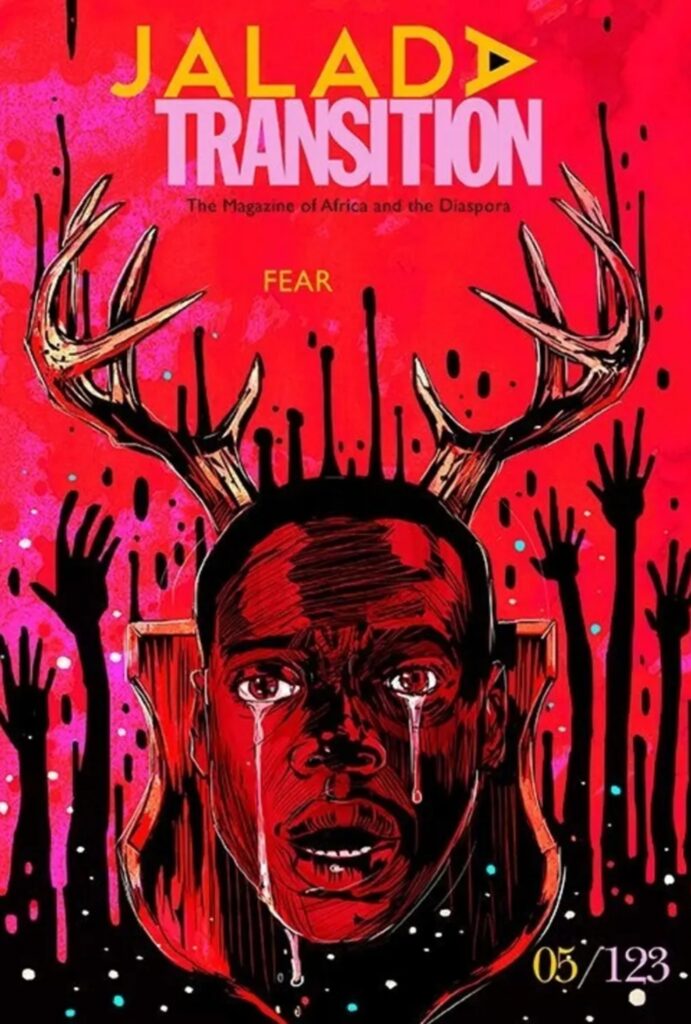

The anthologies don’t have introductions, nor are there mission statements or manifestos; there is only the writing.Their first anthology is JA00: Sketch of a Bald Woman in the Semi-nude and Other Stories. Their second anthology was groundbreaking: JA01: Sext Me Stories and Poems, which is an “attempt at fictionalizing sexual experiences in ways that were rare, in ways that our readers and critics thought broke the implied modesty of our fictional boundaries.” Their third is the much-acclaimed JA02: Afrofuture(s), which “sought to capture multiple and alternative ways of imagining futures – as Africans.” Their fourth, a collection of flash fiction, is a collaboration with Writivism: JA03: My Maths Teacher Hates Me and Other Stories. Their fifth is the game-changing JA04: The Language Issue which “celebrates language through fiction, poetry, spoken word, visual art and essays, in 23 African languages as well as English and French.” It has been called “the most ambitious and robust anthology on African languages on the continent to date.” Their sixth anthology is The Translation Issue 01, which published a short story by Ngugi wa Thiong’o in 33 languages, making it perhaps the single most translated short story in history. The story had since been translated into more than 60 languages, 40 of which are African languages. Their seventh anthology, a collaboration with Transition magazine, is forthcoming in June: Jalada 05/Transition 123 Fear Issue. This year, the collective embarked on another unprecedented event: Africa’s first mobile literary festival which covered five countries in East Africa.

As with anything new and experimental, the quality of the writing is uneven: Sometimes raw and incandescent, it’s as likely to be interestingly incoherent as heart-stoppingly precise. But the collective is bigger than the sum of its parts, and the project’s ambitions are transformative. By self-publishing online—and by working in a spirit of collective collaboration—Jalada’s themes in its first year of existence form a checklist of the topics that someone like Moses Kilolo might struggle to find on the shelves of a Nairobi library: insanity, sex, technology, and the future. Because a top-heavy pantheon of (mostly male) writers from the 1960s and ’70s has dominated African literary publishing for decades, African literature has often been backward-looking and history-oriented. Jalada made a clean break, even establishing a commitment to gender parity from the beginning. (Original contributor Anne Moraa was blasé when I asked her about this: “If you are open to the best work, you will achieve gender parity by default,” she said, though she also gave credit to the original workshop for being gender balanced.)

The drive behind the formation of Jalada, why it began its mission, and its impact so far: these are the things that a new essay by Aaron Bady, editor of The New Enquiry, shines light on.

It began with a workshop for young writers in Nairobi in 2013, organized by the Kwani Trust and the British Council. As Moses Kilolo recalls, he had never attended a writing workshop before. Like so many of his peers, he had been toiling alone: Each day he would haunt his university library, struggling in his own writing to imitate the English-language classics that he found on the shelves. It was a remarkably well-stocked library, as he remembers it, the best a young writer could hope for. Yet while he had produced a few halting efforts at prose, he hadn’t yet “come out” as a writer. He stayed in the stacks. It was only after the three-day workshop with a dozen other young writers, he says, that the brilliance of his peers pulled him out of the library—helped him to realize what he could never accomplish alone. “I wasn’t as good as I thought,” he laughs. “They tore my work apart! It was moving to know that there’s so much more possibility.”

In 2015, Jalada began its most ambitious project yet: to go beyond the handful of colonial languages in which most African writers write—English, French, Portuguese, and Arabic—and explore the thousands of mother tongues that the vast majority of the continent’s people speak. With more than 3,000 languages spoken by significant populations, Africa’s everyday polylingualism defies most Western understanding. In Kenya, for example, it’s common to speak one language in the streets, another in school, and another in the family home (Swahili, English, and an ethnic or tribal language like Kamba, Kikuyu, or Luo). But exceptions outweigh even this very rough norm; Nairobi urbanites might speak Sheng more than either Swahili or English (the languages of which it is a patois), while interethnic families tend to speak multiple languages. Anywhere you find immigrant communities (which is everywhere), the linguistic cocktail gets mixed in yet other ways.

The only generalization one can venture is this: If there’s one thing that unites Africa—that nearly all Africans have in common—it’s the same polylingualism that divides it, an irony that has haunted African literature since its beginnings. It has taken a project like Jalada to do something about it.

Before colonization and the imposition of European languages, the continent’s poetics were oral, dispersed across Ewe, Shona, Kiswahili, Luganda, Igbo, and thousands of other languages. When African literature began to be written, published, and read in the early part of the 20th century, it was in the context of imperialist globalization, a Pan-Africanism that was invariably expressed in the languages of the colonizers. Indeed, English, French, Portuguese, and Arabic provided the literary infrastructure that brought writers and readers across Africa into contact with each other, sometimes for the first time in history: Nigerians could read Kenyans in English, Ivorians could read Mauritanians in French, and novels by Tayeb Salih of Sudan (in Arabic) or Pepetela of Angola (Portuguese) could crisscross the continent in translation. But that was where it usually stopped; translations from African languages were rare (and mostly ethnographic), while translations between African languages were almost non-existent.

For most African writers, then and now, the languages of the former colonizers have been the only pragmatic choice. Faced with a nation speaking over 300 languages, for example, Chinua Achebe wrote in English, the only language most Nigerians shared. Rare exceptions prove the rule: When Ngugi wa Thiong’o vowed to write only in his native Gikuyu, in the 1970s, his polemic made waves but few converts. His manifesto, Decolonizing the Mind, has been debated and fought over for decades and remains a lightning rod for controversy in African literary circles. But the cruel irony is that most still read him in English. Without a strong Gikuyu publishing industry—in a country where Gikuyu speakers make up around 20 percent of the population—even Ngugi’s main Kenyan audience will always read him in English translation.

In 2015, Jalada published an anthology of original stories and poems both in the authors’ own respective languages (many of which were African) and in a variety of translations. Kilolo’s “An Empty Wall,” for example, is presented both in English and in Junior Moyo’s Ndebele translation (a language spoken in Zimbabwe). Edwige-Renée DRO wrote “Pneu Secours” in French and translated it into English herself, while Mazhun Idris made the translation into Hausa (spoken in northern Nigeria). But this was just a prelude to the group’s most striking translation project: In the next anthology, they took a story donated by Ngugi wa Thiong’o (“Ituika Ria Murungaru” in Kikuyu, “The Upright Revolution” in English) and translated it into 62 languages (and counting).

The feeling was general among the workshop’s participants. At first they stayed in touch out of a spontaneous desire to keep the conversations going. But after Okwiri Oduor—who would win the Caine Prize for African Writing later in the year—set up a Google group named Jalada, after the word for library in Kiswahili, the group began to evolve into something more concrete. As the members began writing, and editing each other’s work, they also began talking about what hadn’t been written yet, and what needed to be. They began building their own library: A few months after the workshop, they set up a bare-bones website (jalada.org) where they published an anthology of original work loosely themed around the notion of insanity, Sketch of a Bald Woman in the Semi-Nude and Other Stories.

It had been an easy choice to publish on the Internet: It was free, it was easy, and they had complete control. As the word spread—and as the inaugural anthology did the rounds on social media—they began hearing from writers across the continent, asking if they could submit to the next anthology. Jalada’s editors said yes. The second collection—Sext Me: Poems and Stories, on the intersections of sex and technology, and twice as long as the first—included a handful of participants from outside Kenya, as well as Jalada’s first official call for submissions. Exactly a year after the first anthology, Afrofuture(s)—a three-part shelf-buster of Africanist speculative fiction—had close to a majority of non-Kenyan writers.

As the library has grown from a roomful of young Nairobians to an ongoing conversation that spans the continent—with email, Skype, and social media allowing members in a half-dozen countries to stay in touch—it’s become clear that Jalada is where the future of African literature is being written. A project with a pan-Africanist scope might have drowned under the logistics of communication and distance, or lost its energy in fundraising. Instead, meetings have yielded true mentorships and editorial relationships, and correspondences have blossomed into long-term collaborations, as the contributors to each anthology have become a part of the broader network. The management team remains mostly Kenyan—allowing semi-regular face-to-face meetings—but the structure is as horizontal and outward-looking as possible. Members from Namibia, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Somalia make up the core group, with an even broader network of contributors and collaborators. Richard Ali in Nigeria and Edwige-Renée DRO in Côte d’Ivoire have been crucial to the project’s expanding reach, for example, both for their editorial expertise and for connecting Jalada to new writers in West and Francophone Africa. Building connections with North Africa is the next hurdle.

While the accomplishment is remarkable, of course, the anthology can’t really be read in the conventional manner at all: Few can read Ngugi’s folkloric parable about why humans walk upright in more than a handful of the languages that the anthology offers. Rather, the point is to imagine a different kind of library. “At a personal level, what Jalada has done is akin to recapturing stolen lands,” as founding editor Richard Oduor Oduku told me. “We have recaptured the authority to imagine our own futures, including what languages we will, or we can, employ.” This sentiment was general among the translators I spoke with; Rwandan Louise Umutoni, for example, described translation into European languages as a kind of brain drain, and explained that, instead of Africa’s literary resources enriching languages like English, Jalada reversed the flow, translating European works into African languages starved for the written literary word.

In November 2017, Jalada staged a reading of the story in Nairobi, in seven languages: Sheng, Kiswahili, Dholuo, Kikuyu, Kiluhya, Kinyarwanda, and English. Few in the audience would have been fluent in more than a few of them. But, as Kilolo recalled, the revelation was seeing seven different languages in the same place, before the same audience, uniting rather than dividing. “People were thrilled to see so many languages at once,” he said. “We have to do away with the notion that speaking a different language divides people.”

Jalada’s “about” page is brief and to the point: a “pan-Africanist writers’ collective” whose goal is “to publish literature by African authors regularly by making it as easy as possible for any member to publish anything.” This tautology—their goal is to publish the things they are publishing—tells a story of its own: Jalada is just the work itself, without money, pretensions, or ego. The anthologies don’t have introductions, nor are there mission statements or manifestos; there is only the writing

2) “CHIMURENGA”

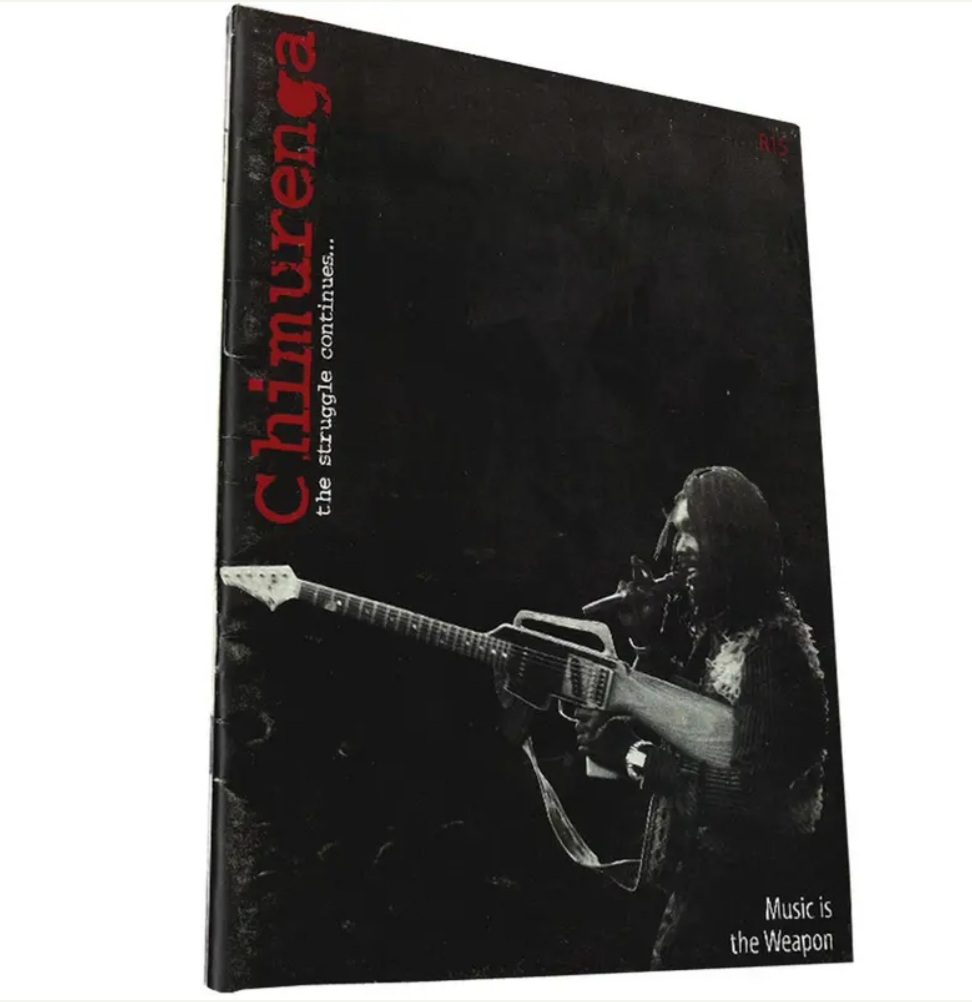

“Chimurenga” is the Shona word for “Liberation” . The founding editor of Chimurenga magazine, Ntone Edjabe, is a Cameroonian journalist and a DJ who engages literature, music and politics with a rebel spirit that reflects the magazine’s name. Like Transition, Edjabe founded Chimurenga in 2002 in Cape Town at a time where South Africans were having lively discussions about life during and after political and social revolutions.

Chimurenga is a publication of arts, culture and politics from and about Africa and its diasporas, founded and edited by Ntone Edjabe. Both the magazine’s name (Chimurenga is a Shona word that loosely translates as “liberation struggle”) and the content capture the connection between African cultures and politics on the continent and beyond.

Chimurenga was launched in 2002 as a magazine promoted by Kalakuta Trust and founded by Ntone Edjabe. It is based in Cape Town, South Africa, but its network is international. Chimurenga focuses on Africa and its diaspora, aiming at capturing the connection between African cultures and politics on the continent and beyond. Chimurenga gradually began developing a series of publications, events (called Chimurenga Sessions) and specific projects.

Chimurenga is reviewed by newspapers and magazines and it is presented inside conferences, events and exhibitions. In 2007, it was part of the Documenta magazine project within Documenta exhibition in Kassel; in 2008 it was reviewed by an article of The New York Times. Its director Ntone Edjabe talks about the magazine and its approach during numerous interviews and conferences also at the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Art Academy in Berlin in 2005, at the Dakar Biennale in 2006 and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2009. In particular the capacity of Chimurenga to influence ideas and writing and its role as an innovative educational model is recognised by initiatives such as Meanwhile in Africa… in 2005, and Learning Machines: Art Education and Alternative Production of Knowledge in 2010. In 2010 Chimurenga began a collaboration with the magazine Glänta to translate Chimurenga into Swedish.

In addition to its magazine, Chimurenga produces other publications, events and specific projects.

Magazines

The first issue of Chimurenga magazine was published in April 2002. Each issue has a specific theme. Initially a quarterly, Chimurenga now appears approximately three times a year. Interrogating the superficial has always been the core agenda of the publication. The various renegades are captured in a series of profiles “thinking out loud”. Chimurenga shies away from the Q&A format and includes deconstructed and imagined interviews, surreal short stories and poetry and other devices that challenge strict notions of fact and fiction. Covers are equally indicative of the orientation of a journal which is at once theoretical, erotic, and provocative. One cover featured the words of “Strange Fruit“, the song about Southern lynchings that Billie Holiday immortalised. Another featured Neo Muyanga‘s portrait of Steve Biko‘s bruised face. The first edition showed Peter Tosh at a gig in Eswatini in the early 1980s, pointing an AK-47-shaped guitar in the direction of South Africa and chanting down Babylon.

Chimurenga orients itself not only to radical people that form its immediate target group, but also to the lay reader. It is distributed in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Kenya, Eswatini, Botswana and Ghana. Its distribution has seen it read on campuses in Germany, the United States, Great Britain and France.

The magazine has featured work by emerging as well as established voices including Njabulo Ndebele, Lesego Rampolokeng, Santu Mofokeng, Keorapetse Kgositsile, Gael Reagon, Binyavanga Wainaina, Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, Boubacar Boris Diop, Tanure Ojaide, Dominique Malaquais, Stacy Hardy, Goddy Leye, Zwelethu Mthethwa, Mahmood Mamdani, Jorge Matine, and Greg Tate, among others.

- Chimurenga Vol. 1, Music Is The Weapon, April 2002

- Chimurenga Vol. 2, Dis-Covering Home, July 2002

- Chimurenga Vol. 3, Biko in Parliament, November 2002

- Chimurenga Vol. 4, Black Gays & Mugabes, May 2003

- Chimurenga Vol. 5, Head/Body(&Tools)/Corpses, April 2004

- Chimurenga Vol. 6, The Orphans Of Fanon, October 2004

- Chimurenga Vol. 7, Kaapstad! (and Jozi, the night Moses died), July 2005

- Chimurenga Vol. 8, We’re all Nigerian!, December 2005

- Chimurenga Vol. 9, Conversations in Luanda and Other Graphic Stories, June 2006

- Chimurenga Vol. 10, Futbol, Politricks & Ostentatious Cripples, December 2006

- Chimurenga Vol. 11, Conversations With Poets Who Refuse To Speak, July 2007. The magazine produces a presentation video of the issue. The issue is translated into Swedish and published by the magazine Glänta 2/2010.

- Chimurenga Vol. 12/13, Dr. Satan’s Echo Chamber, March 2008. The magazine produces a presentation video of the issue.

- Chimurenga Vol. 14, Everyone Has Their Indian, April 2009. Dedicated to Third World projects and links, real and imaginary, between Africa and South Asia. The magazine produces two presentation videos of the issue.

- Chimurenga Vol. 15, The Curriculum is Everything, May 2010. The issue is conceived as a second chance to write history: a low-tech time-machine that allows produce a back-issue of a newspaper and to analyse xenophobic events that took place in South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya in the week 11–18 May 2008. The issue is produced by an online editorial board that involves writers, artists and journalists in collaboration with the magazines Chimurenga and Kwani? and the publishers Cassava Republic Press.

- Chimurenga Vol. 16: The Chimurenga Chronicle, October 2011 — described as “the once-off edition of an imaginary newspaper…. Set in the week 18–24 May 2008, the Chronic imagines the newspaper as producer of time – a time-machine…. An intervention into the newspaper as a vehicle of knowledge production and dissemination, it seeks to provide an alternative to mainstream representations of history, on the one hand filling the gap in the historical coverage of this event, whilst at the same time reopening it. The objective is not to revisit the past to bring about closure, but rather to provoke and challenge our perceptions.”

Chimurenga also has a monthly online edition that presents other short contributions not directly connected to the themes of the paper publication.

Chimurenganyana

Chimurenganyana is a series of low-cost publications and a distribution system. A selection of articles from Chimurenga are printed on small sizes and are sold by street vendors who normally sell cigarettes. Each edition is focused on a specific theme.

- Julian Jonker, A Silent Way: Routes of South African Jazz, 1946-1978

- Keziah Jones, When You Kill Us, We Rule!: Fela Anikulapo Kuti‘s Last Interview

- Dominique Malaquais, Blood Money: A Douala Chronicle

- Njabulo Ndebele, Thinking of Brenda

- Achille Mbembe, Variations on the Beautiful in the Congolese World of Sounds

- Odia Ofeimun, In Defence of the Films We’ve Made

Chimurenga Library

The Chimurenga Library is a selection of magazines and publications that – according to Chimurenga – influence thinking and writing in Africa. The selection is presented on an online database under CC-BY-SA compatible with Wikipedia; it presents general information on the magazines and a sort of genealogy that links publications to one another.

Magazines and publications presented on the Chimurenga Library are: African Film, Amkenah, Black Images, Chief Priest Say, Civil Lines, Ecrans d’Afrique, Frank Talk, Glendora Review, Hambone, Hei Voetsek!, Joe, Autre Afrique, Lamalif, Mfumu’eto, Molotov Cocktail, Moto, Okyeame, Revue Noire, Savacou, Souffles, Spear, Staffrider, Straight No Chaser, The Book of Tongues, The Cricket: Black Music in Evolution, The Liberator Magazine, The Uncollected Writings of Greg Tate, Third Text, Tsotso, Two Tone, Unir Cinéma, Wietie, Y Magazine (first five issues).

Artists, writers and intellectuals who have contributed texts and videos to the Chimurenga Library include: Rustum Kozain, Vivek Narayanan, Patrice Nganang, Khulile Nxumalo, Sean O’Toole, Achal Prabhala, Suren Pillay, Lesego Rampolokeng, Tracey Rose, Ivan Vladislavic, Barbara Murray, Akin Adesokan, Nicole Turner, Tunde Giwa, Brian Chikwava, Judy Kibinge, Olu Oguibe, Sam Kahiga, Mike Abrahams, Sola Olorunyomi, Marie-Louise Bibish Mumbu, Nadi Edwards, Brent Hayes Edwards, Sharifa Rhodes Pitts, Jean-Pierre Bekolo and Aryan Kaganof.

In 2009 Chimurenga Library is shown with the title “Chimurenga Library: An introspective of Chimurenga” at Cape Town Central Library with a series of multimedia itineraries (reading routes and sound posts) and live events (music, readings, meetings with authors, projections and wiki workshop during which students are involved in producing Wikipedia articles). The idea of the presentation is to rethink a library as a laboratory which can trigger curiosity, adventures, critical thinking, activism, entertainment and random reading. The show presents pan-african independent periodicals, and the exhibition Why Must A Black Writer Write About Sex, a selection of texts on sex from African literature which confront stereotypes on sexuality and literature genres.

What makes Chimurenga unique is not only the amazing writing that they publish, but the ways the platform evokes other mediums with literature. Chimurenga has various publications including The Chronic (a newspaper styled magazine), the African Cities (publication that explores urban life), and the Pan African Station (Online radio and Pop-Up Studio). They’ve published the works of the writers like Lebo Mashile, Stacy Harder, Wainana, Chimamanda Adichie and Percy Zvomuya.

Last Month, Chimurenga posted on Facebook that they were being forcibly removed from their home in Cape Town where they had been based for 20 years. While the magazine will continue publishing its work, it’s a reminder to support organizations that are crucial to African Literature.

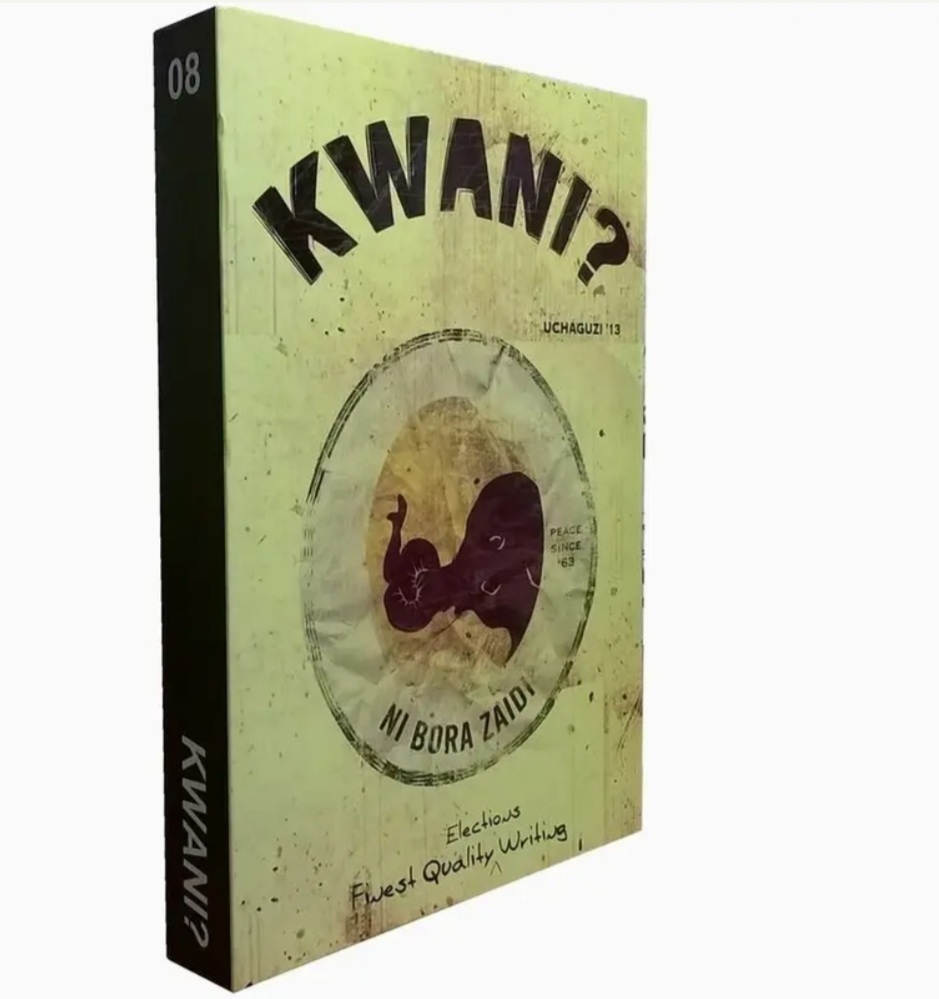

3) “KWANI”

“You know you’ve been sleeping for a long time. All of a sudden someone just comes and paints the country red, blue, green, and light. So everyone just comes out of their bedroom. And everyone who hasn’t been cleaning their house starts cleaning it. And those with house too clean starts throwing mud on the wall”. This is how Binyavanga Wainana described the artistic revolution in 2002 that led to the creation of KWANI? Where Waina became the first editor.

“KWANI” began after a group of Kenya writers, artists, and journalists became frustrated with the slow publishing scene in the country that mostly accommodates earlier writers like Ngugi from the “Transition” and “Black Orpheus” generation. A new publication was created in 2003 for emerging writers that has lead to the incredible literature we enjoy today from Kenya.

Kwani Trust is a literary network based in Kenya. Founded in 2003 by Binyavanga Wainaina and other African writers. It is dedicated to nurturing and developing Kenya’s and Africa’s intellectual, creative, and imaginative resources through strategic literary interventions. Kwani Trust has significantly shaped the landscape of East African literature, promoting a new generation of writers and artists. It publishes the seminal literary magazine “Kwani?”, and has been instrumental in launching the careers of authors such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Yvonne Owuor. Kwani Trust’s impact on the African literary scene is profound, highlighting themes of political activism, social justice, and cultural identity through its publications, workshops, and literary festivals. Notably, its publications have received international acclaim, with “Kwani?” often showcased at global literary events. The Trust also focuses on digital storytelling through multimedia and visual arts to reach broader audiences.

Kwani? (derived from the Sheng slang so what?) was a prominent African literary magazine headquartered in Kenya. It has been hailed as “undoubtedly the most influential journal to have emerged from sub-Saharan Africa”.

The magazine originated from discussions among a group of writers based in Nairobi during the early 2000s. Its inception was led by Binyavanga Wainaina, who initiated the project after winning the 2002 Caine Prize for African Writing. The inaugural printed edition was released in 2003.

Kwani? was produced by the Kwani Trust, an organization dedicated to fostering Kenya’s and Africa’s intellectual, creative, and imaginative resources through strategic literary initiatives. The organization receives substantial funding from the Ford Foundation.

During its run, the magazine evolved into a significant platform for African continent literature and has propelled the careers of various writers, including Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, who won the 2003 Caine Prize; Uwem Akpan, acclaimed author of the bestselling short-story collection Say You’re One of Them, and Billy Kahora, now the magazine’s managing editor. Each edition of the journal comprises over 500 pages of new journalism, fiction, experimental writing, poetry, cartoons, photographs, ideas, literary travel writing, and creative non-fiction.

Each volume of Kwani? revolved around a central theme. For instance, the seventh issue (2012/3), titled “Majuu” (a Sheng word meaning “overseas”), was “a 570-page testament to the journal’s diasporic roots”.

After the Ford changed its funding models in East Africa and ended support programs for arts and the media in 2014/15, “Kawani?” ceased publication.

Kwani Trust

Kwani Trust is a regional literary organization and community of writers focused on fostering the development of the region’s creative industry. Their efforts encompass publishing and distributing contemporary African literature, providing training opportunities, hosting literary events, and establishing global literary networks.[16] The Kwani? Literary Festival is held biennially, gathering literary figures from Kenya and beyond to explore various topics through the lens of the continent’s historical, current, and emerging literature.[17]

Kwani? Manuscript Project

The Kwani? Manuscript Project was initiated in 2012 as a literary prize aimed at recognizing unpublished fiction manuscripts from African writers across the continent and in the African diaspora. The project established a judging panel that included notable figures such as Jamal Mahjoub, Ellah Allfrey (deputy editor of Granta magazine), Helon Habila, Simon Gikandi, Mbugua wa Mungai (chairman of Kenyatta University‘s Literature Department), and Irene Staunton (associated with Weaver Press in Zimbabwe). On 12 April 2013, the project unveiled a longlist of selected manuscripts, and later in July 2013, the winner was announced as Ugandan writer Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi. The runner-up position was awarded to Liberia’s Saah Millimono for One Day I Will Write About This War, and third place was secured by Kenya’s Timothy Kiprop Kimutai for The Water Spirits.

Issue List

- Kwani? 01 (2003) – Showcased diverse narratives.

- Kwani? 02 (2005) – Explored contemporary Kenyan and African identity.

- Kwani? 03 (2006) – Highlighted urban life in Kenya.

- Kwani? 04 (2007) – Delved into post-election violence and reconciliation

- Kwani? 05 (2008) – Was themed around “Hustle” to focus on economic and social survival.

- Kwani? 06 (2010) – Addressed migration and the experiences of Africans abroad.

- Kwani? 07: Majuu (2012) – Explored the African diaspora.

- Kwani? 08 (2015)

The journal has published works by writer like Yvonne Owuor, Parselelo Kantai, Andia Kisia, Uwem Akpan and Billy Kahora.

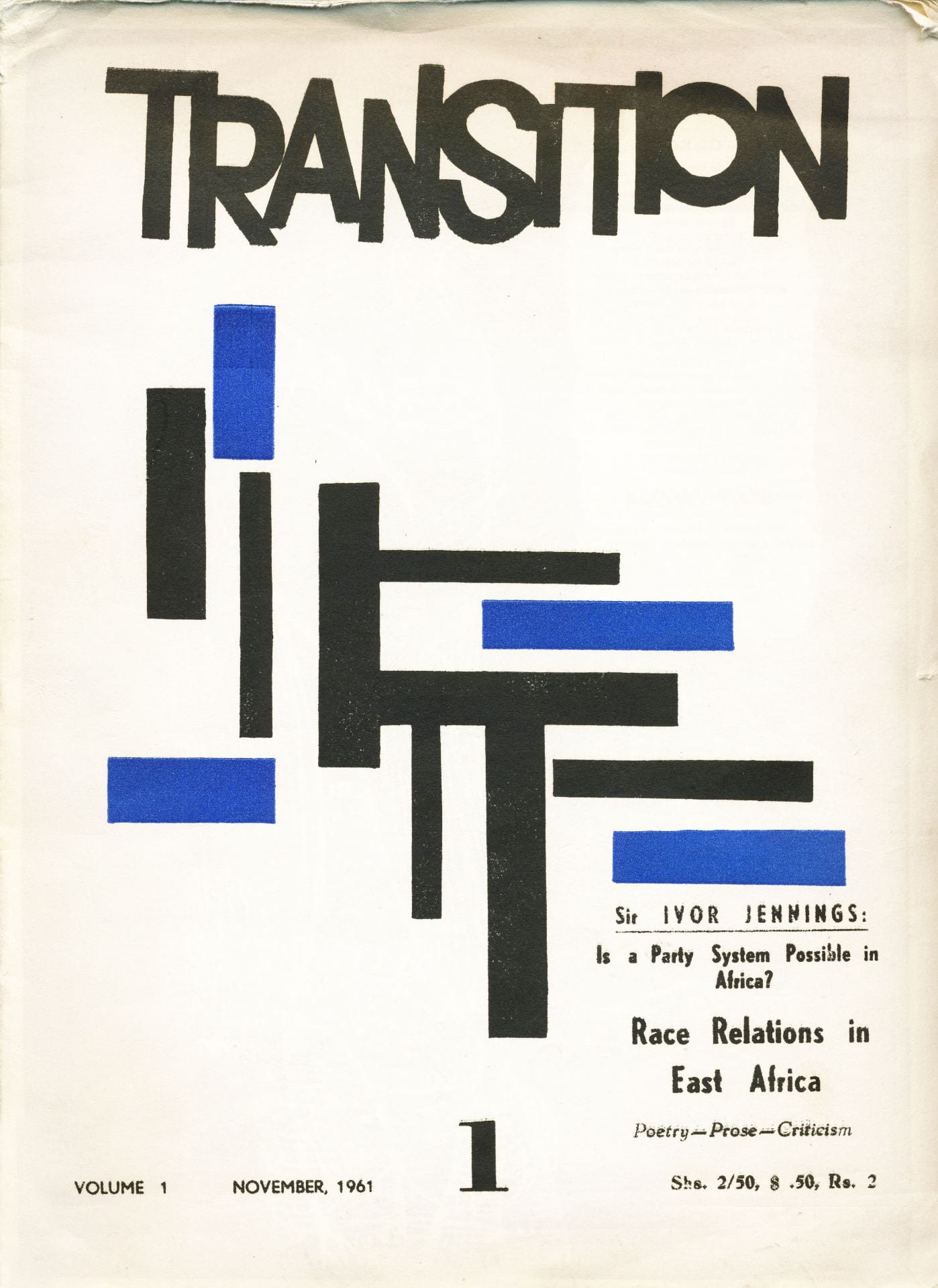

4) “TRANSITION MAGAZINE”

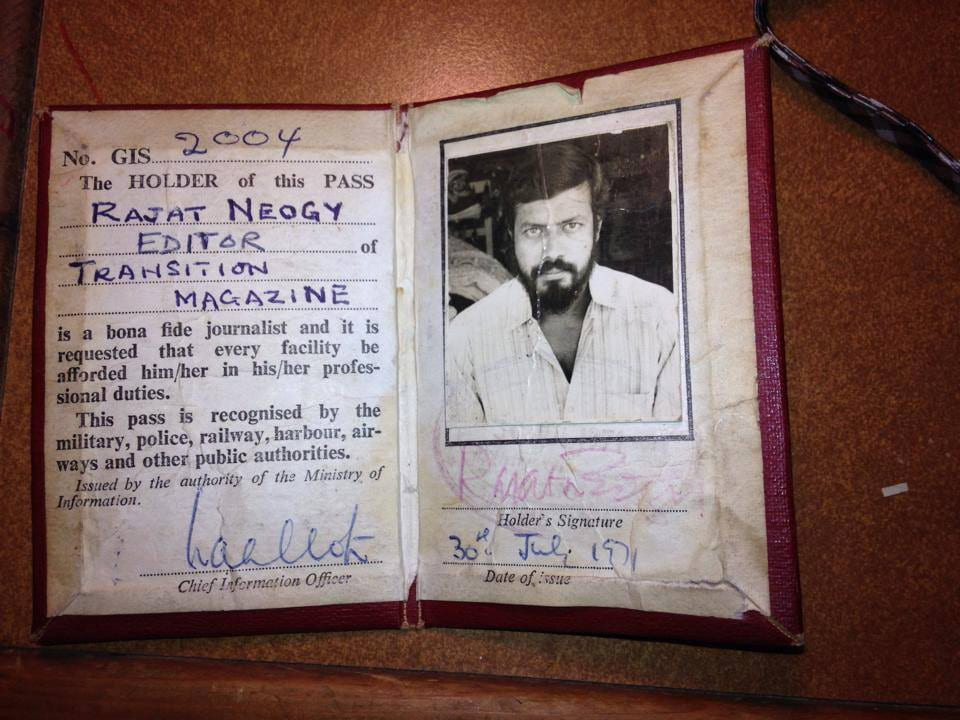

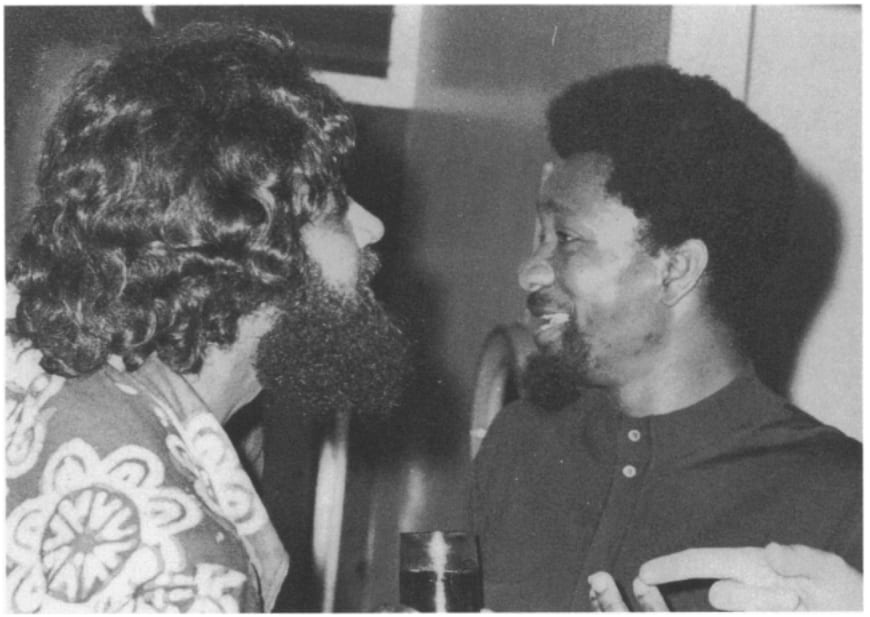

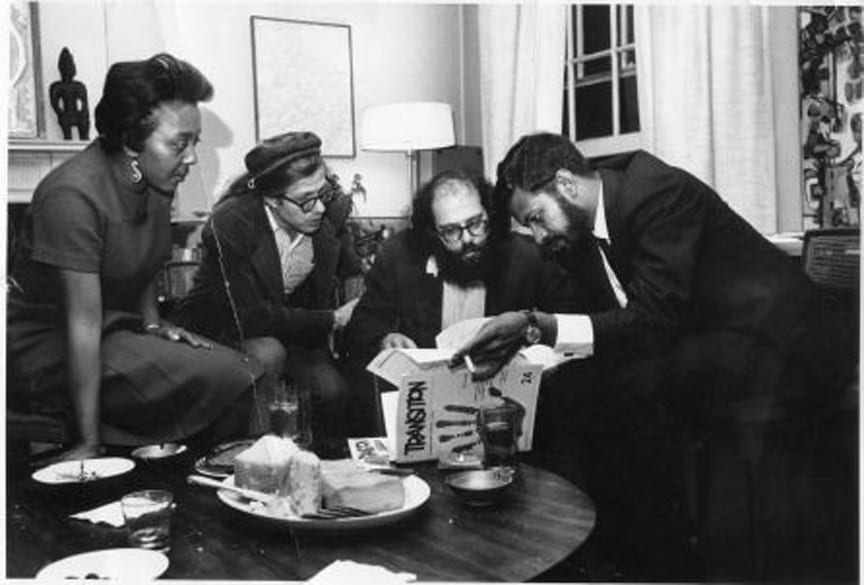

The name TRANSITION reflects the moment that birthed the magazine in 1961. Transition was founded by Rajat Neogy in Kampala, when Uganda, like other African nation, was gaining it’s independence. Like Black Orpheus, the magazine published notable writers like Achebe, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Nadine Gordimer, and Taban lo Liyong when they were new writers.

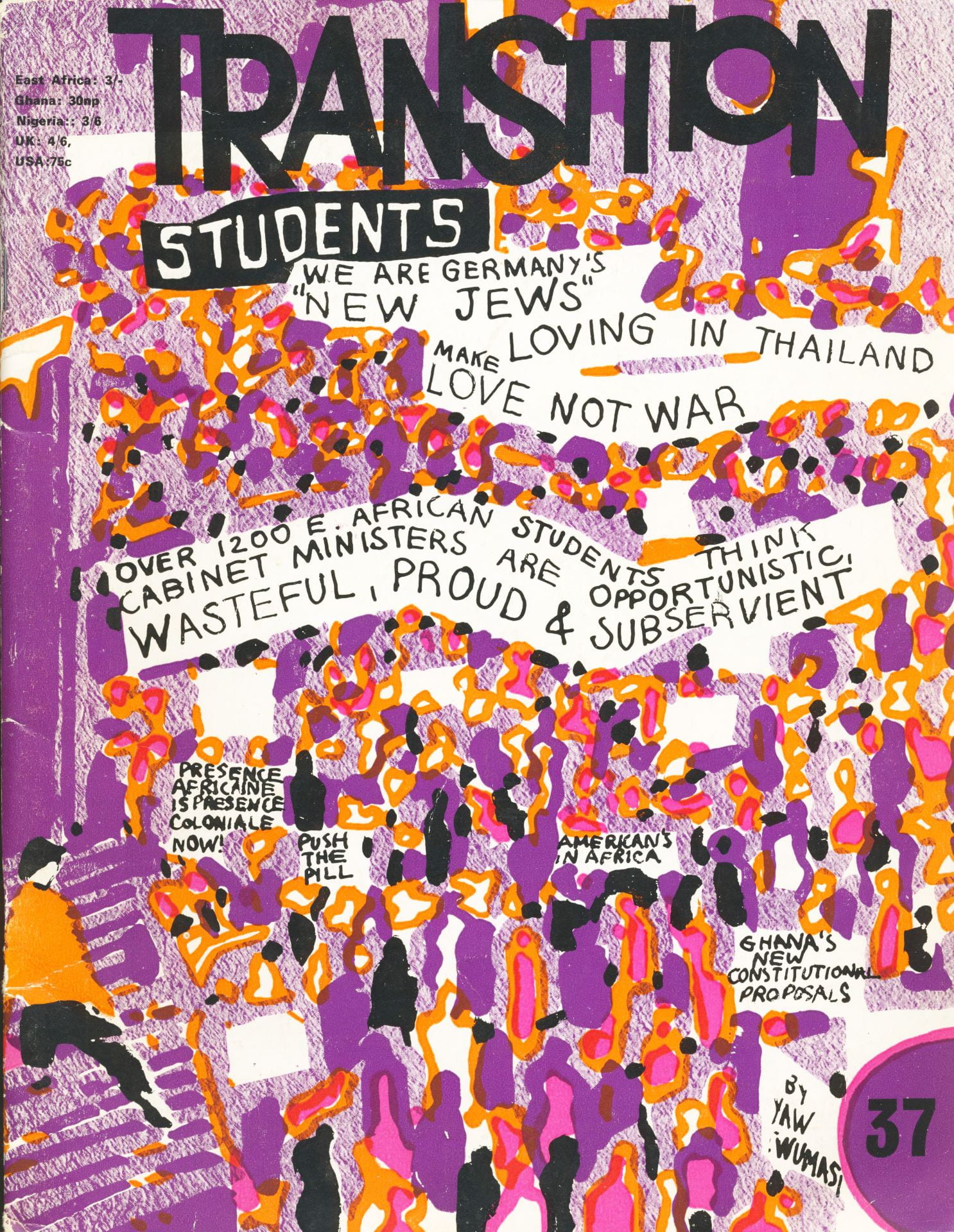

Transition had some of the most epic debates about African literature over the years, especially in the earlier issue when writers were throwing some old school poetic shade against each other (Soyinka began an essay to his critics with this line, “Pretenders to the Crown Of Pontifex Maximus Of African Poetics must learn to mind the thorn”.) The magazine has had fearless takes on politics that eventually forced it to be transferred to Nigeria when Soyinka was editor, and later to the United States. Transition is now housed at Havard University and is still producing provocative work like the post-Trump election issue appropriately titled White A$$holes.

Transition Magazine was established in 1961 by Rajat Neogy as Transition Magazine: An International Review. It was published from 1961 to 1976 in various countries on the African continent, and since 1991 in the United States. In recent years it has been published between twice and four times per year by Indiana University Press, since 2013 on behalf of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University.

Upon his 1961 return to Kampala, Uganda, from studies in London, 22-year-old Rajat Neogy established Transition Magazine: An International Review. The magazine was partially funded by the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an anti-communist advocacy group whose ties to the Central Intelligence Agency were then unknown. Transition served as a major literary platform of East African writers and intellectuals during the Cold Wars In 1962, Christopher Okigbo was appointed as editor of a West African edition.

In 1968, the Ugandan government jailed Neogy for sedition; the magazine had criticized President Milton Obote‘s proposed constitutional reforms. After Neogy’s release, the magazine began publication in Ghana from 1971. Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka became editor in 1973, but in 1976 the magazine was forced to cease publication for financial reasons.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr, previously a frequent contributor to Transition when published in Ghana, revived the magazine in 1991. Under his leadership, Transition evolved into “an international magazine about race and culture, with an emphasis on the African diaspora“.

It is not clear when the journal was first published in the US, but since the Hutchins Center was established in 2013, it has supported publication of the journal.

As of 2020 the editor is Alejandro de la Fuente. Soyinka is chair of the editorial board, and Gates and Kwame Anthony Appiah are named as the publishers.

Former editors

Former editors include:

- Rajat Neogy

- Wole Soyinka

- Henry Finder

- Michael C. Vazquez

- F. Abiola Irele

- Laurie Calhoun

- Tommie Shelby

- Glenda Carpio

- Vincent Brown

Transition Magazine Timeline

Uganda, 1961

Transition Magazine is founded in Kampala, Uganda, (the year before independence) by Rajat Neogy. Transition becomes a center of debate during the beginning of decolonization.

Neogy jailed (after the publication of T37) in Uganda by President Milton Obote for publishing “subversive” writings.

1968

1969

Neogy leaves Uganda in 1969 and begins operating the magazine from Accra, Ghana in 1971.

Neogy hands over editorship to Soyinka, who brings it to Nigeria.

1973

1990

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Anthony Kwame Appiah, and Wole Soyinka resurrect the magazine in 1990. It is first run under the auspices of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, and then the Hutchins Center of African and African American Research at Harvard University.

Our History

Explore Our Rich History

Transition was founded in 1961 in Uganda as an East African literary magazine. The brainchild of a twenty-two year old writer of Indian descent named Rajat Neogy, it quickly became Africa’s leading intellectual magazine during a time of radical changes across the continent.

Rajat Neogy

Founding Editor

…the ultimate purpose of a literary magazine will always be to herald change, to forecast what new turn its culture and the society it represents is about to take. It will do this by sometimes allowing prejudice and temporary obsessions to be aired [and] by being permissive to radical innovations.

November, 1961

First Issue

Transition’s first issue draws its radical vitality from a mixture of genres: poetry, short fiction, longer think pieces on independence, the party system, Uganda’s economy, race relations in East Africa, and the place of the Catholic missionary–as well as profiles, book reviews, anonymous diary entries, short dispatches from the political arena, and excerpts from expatriates’ correspondence home.

5) BLACK ORPHEUS: A JOURNAL OF AFRICAN AND AFRO-AMERICAN LITERATURE

Based in Nigeria, Black Orpheus was ground-breaking as the first African Literary periodical on the continent publishing works in English. It was founded in 1957 by German Editor Ulli Beier, and was later edited by Wole Soyinka, Es’kia Mphahele, and Abiola Irele. The magazine stop printing in 1975.

African poetry has this in common with surrealism, that the image does not merely stand for what it describes. But at the same time it differs from it. because there is no arbitrary interchanging, the image always symbolizes the reality that lies behind the temporary’ world. Leopold Sedar Senghor has expressed this as follows: “The image is not an equation, but an analogy, a super-real image. An object does not mean what it represents, but what it suggests, or what it creates. Every conception is an image. And the image is not an equation but a symbol, an ideogram.

At a time when African writers needed spaces where they could simply gather and enjoy each other’s works, the magazine was started to promote African literature, publishing the works of literary giants like Chinua Achebe, Ama ata Aidoo, and Christopher Okigbo in their early career. The best part of the magazine was that it introduced literature from French, Spanish, and Portuguese speaking regions to an English-speaking audience, particularly the translated works of the negritude poets like Aimé Césaire, Birago Diop, and Léopold Senghor.

Black Orpheus Journal Now Publicly Available as a Digital Archive

Black Orpheus: A Journal of African and Afro-American Literature, a major literary journal based in Nigeria, is now available to peruse online, thanks to the digitizing efforts of OlongoAfrica, a new web publication published under The Brick House Collective.

Black Orpheus published some of the most important Anglophone works, including translations of French work, in the post-colonial period, including writing by Léopold Senghor, Aimé Césaire, Gabriel Okara, Dennis Brutus, and Kofi Awoonor. Founded in 1957 by German expatriate editor and scholar Ulli Beier, Black Orpheus broke ground as the first African literary periodical in English, publishing poetry, art, fiction, literary criticism, and commentary. The journal had a series of editors including Janheinz Jahn, Wọlé Ṣóyínká, Christopher Okigbo, Abiola Ìrèlé, among others. Beier’s departure to Papua New Guinea in 1967 saw the end of the first volume, but the journal continued in 1968 under under J. P. Clark and Irele. The journal struggled along in fits and starts before eventually halting its publication in the mid-nineties with six total volumes.

Black Orpheus: A Journal of African and Afro-American Literature was a Nigeria-based literary journal founded in 1957 by German expatriate editor and scholar Ulli Beier that has been described as “a powerful catalyst for artistic awakening throughout West Africa”. Its name derived from a 1948 essay by Jean-Paul Sartre, “Orphée Noir”, published as a preface to Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malgache, edited by Léopold Sédar Senghor.

Beier wrote in an editorial statement in the inaugural volume that “it is still possible for a Nigerian child to leave a secondary school with a thorough knowledge of English literature, but without even having heard of Léopold Sédar Senghor or Aimé Césaire“, so Black Orpheus became a platform for Francophone as well as Anglophone writers.

The Congress for Cultural Freedom, a front group set up by the Central Intelligence Agency, was a funder of the magazine.

History

Black Orpheus was “a journal of African and Afro-American literature” established in 1957 by university professor Ulli Beier. It was produced in Ibadan, Nigeria, and was ground-breaking as the first African literary periodical in English, publishing poetry, art, fiction, literary criticism, and commentary. Its editors included Wole Soyinka and Es’kia Mphahlele (1960–64).

Characterised by its pan-African reach, Black Orpheus also published in English translation the work of Francophone writers, among them Léopold Senghor, Camara Laye, Aimé Césaire, and Hampâté Bâ, as well as playing a significant role in the careers of such notable authors and artists as Wole Soyinka, John Pepper Clark, Gabriel Okara, Dennis Brutus, Kofi Awoonor, Andrew Salkey, Léon Damas, Ama Ata Aidoo, Cyprian Ekwensi, Alex La Guma, Bloke Modisane, Birago Diop, D. O. Fagunwa, Wilson Harris, Valente Malangatana, and Ibrahim el-Salahi. Many of them featured in a 1964 anthology edited by Beier, Black Orpheus: An Anthology of New African and Afro-American Stories, which was published in Lagos, London, Toronto, and New York.

Black Orpheus was highly influential; Abiola Irele – the magazine’s editor from 1968 – wrote in the Journal of Modern African Studies: “The steady development of Black Orpheus over the last seven years amounts to a remarkable achievement. It has succeeded in breaking the vicious circle that seems to inhibit the development of a proper reading public by its continued existence, by its very availability; more than that, it has also gone on to establish itself as one of the most important formative influences in modern African literature.…It can be said, without much exaggeration, that the founding of Black Orpheus, if it did not directly inspire new writing in English-speaking Africa, at least coincided with the first promptings of a new, modern, literary expression and re-inforced it by keeping before the potential writer the example of the achievements of the French-speaking and Negro American writers.”

Beier also founded the Mbari Club, in 1961, a cultural hub for African writers that was closely connected with Black Orpheus, and during the 1960s also acted as a publisher — considered to be the only African-based publisher of African literature at the time — producing 17 titles by African writers.

Having earned a reputation as “the doyen of African literary magazines”, Black Orpheus eventually ceased publication in 1975.

Working with Archivi.ng, a Nigerian non profit digitizing newspapers and other culture materials, OlongoAfrica has scanned all the copies of Black Orpheus journals they obtained as part of the Black Orpheus Revisited Project started in November 2024, and supported by a grant from the Open Society Foundations. Some copies were donated by Prof. Fẹ́mi Euba in Louisiana. The June Creative Art Advisory has also supported this project.

Issues of Black Orpheus have been largely inaccessible for most of the journal’s history. Looking in foreign libraries, bookstores, and private collections OlongoAfrica was able to recover the majority of the journal’s issues, but a few are still missing. Here’s a full list of the digitized content with links to the materials:

- The Metadata (A spreadsheet guide to the content of all of Vol. 1)

- Volume 1: No. 1- No. 22 (1957-1967)

- Volume 2: No. 1, No. 2. (No. 3 still missing) – 1968-1970

- Volume 3: No. 1, No 2 & 3 (combined edition) — 1974-1975

- Volume 4: (still missing)*

- Volume 5: No. 1 (others missing) – 1983

- Volume 6: No. 1, No. 2. (1986 – 1993)

The program’s Black Orpheus fellows will also be able to access the journal’s physical copies through a partnership with libraries in Lagos.

This digitization effort makes public for the first time this incredibly important moment in the development of African literary culture. OlongoAfrica encourages anyone interested in African literature, African visual arts, African history, and the sixties in general to engage with the archive.